|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8221) (tudalen 000_a)

|

HANDBOOK OF

THE ORIGIN OF PLACE-NAMES

IN WALES AND MONMOUTHSHIRE The Rev. THOMAS MORGAN, DOWLAIS.

* Happy is he who knows the origin of things.' 1 MERTHYR TYDFIL: PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY H. \V. SOUTH

EY, " EXPRESS " OFFICE. ISS 7 .

KfTT \ /

THB KBW TORE PUBLIC

LIBSA1T 607559B A8T0B, LENOX AND TILDKN FOUNDATIONS B 1951 I

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8222) (tudalen 000_b)

|

To The Riwt Honourable WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE, IN TOKEN OF PROFOUND RESPECT FOR HIM AS

The Most Honourable and Distinguished Resident in the Principality of Wales, ZbiQ tPolume id H>e6icate& 1^ BY

C *" THE AUTHOR.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8223) (tudalen 000_c)

|

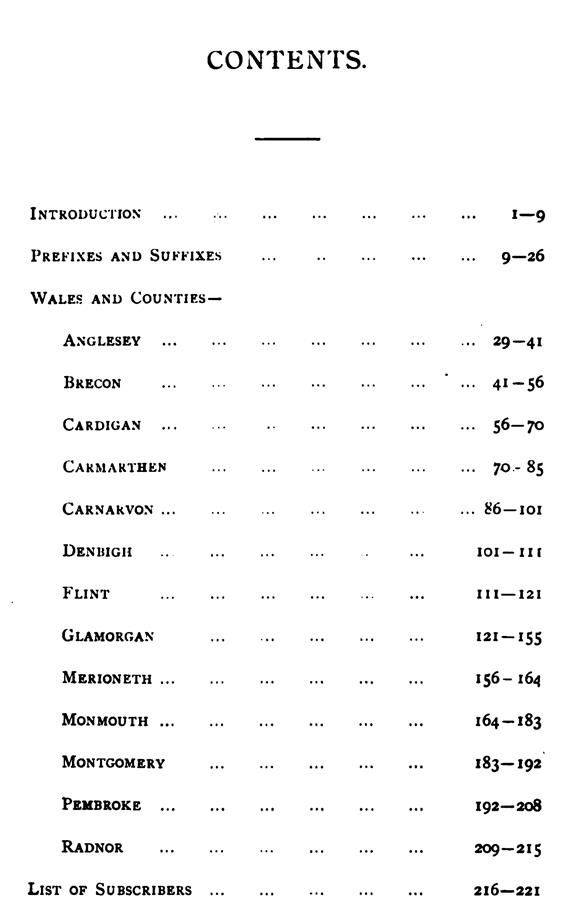

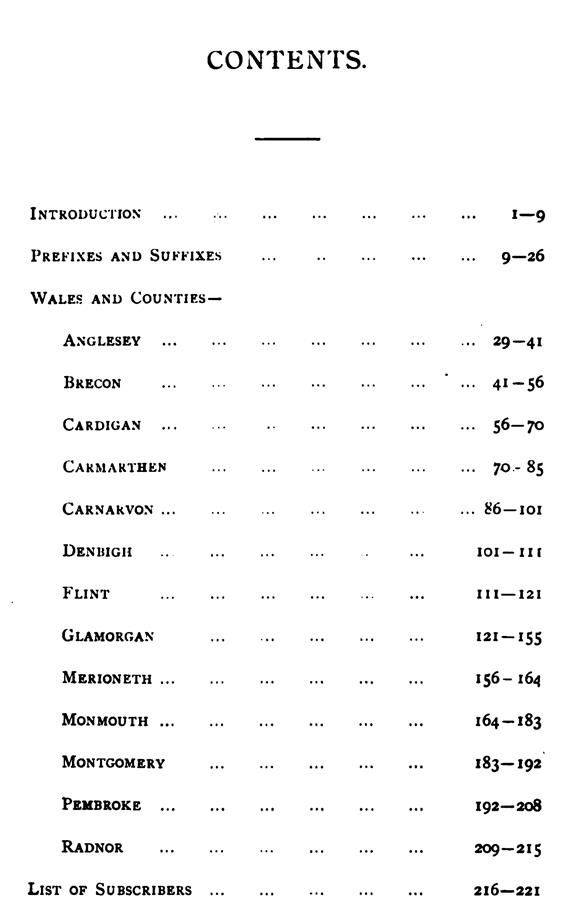

CONTENTS. Introduction Prefixes and Suffixes Wales and Counties Anglesey ... Brecon

Cardigan ... Carmarthen Carnarvon ... Denbigh

Flint Glamorgan Merioneth ... Monmouth ... Montgomery

Pembroke ... Radnor List of Subscribers 1-9

926 29-41 41-56

56-70 7o- 85 86-101

101 in in 121 121-155

156- 164 164-183 183-192

192208 209215 216221

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8224) (tudalen 000_d)

|

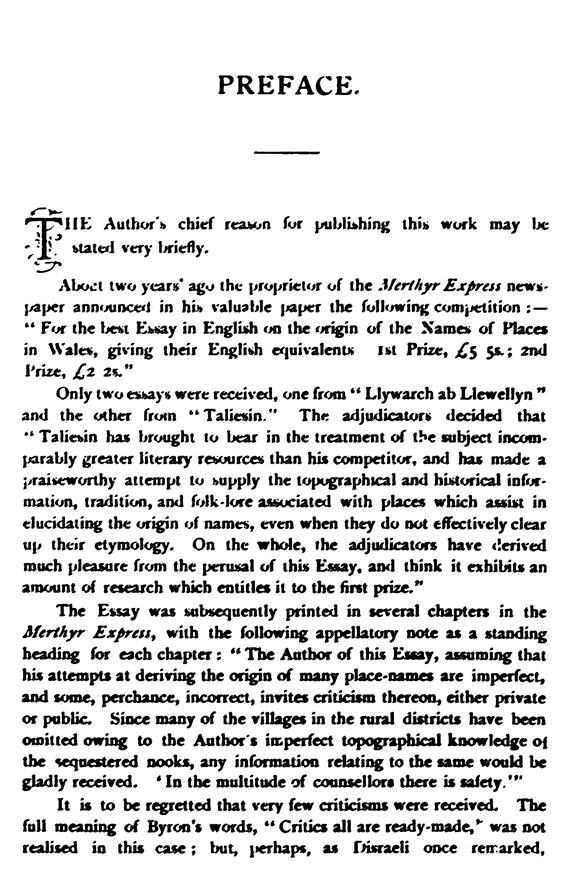

PREFACE. fHE Author's

chief reason for publishing this work may be stated very briefly. <^ Aboct

two years' ago the proprietor of the Merthyr Express newspaper announced in

his valuable paper the following competition: " For the best Essay in

English on the origin of the Names of Places in Wales, giving their English

equivalents 1st Prize, £5 5s.; 2nd Prize, £2 2s." Only two essays were

received, one from '* Llywarch ab Llewellyn " and the other from

"Taliesin." The adjudicators decided that 44 Taliesin has brought

to bear in the treatment of the subject incomparably greater literary

resources than his competitor, and has made a praiseworthy attempt to supply

the topographical and historical information, tradition, and folk-lore

associated with places which assist in elucidating the origin of names, even

when they do not effectively clear up their etymology. On the whole, the

adjudicators have derived much pleasure from the perusal of this Essay, and

think it exhibits an amount of research which entitles it to the first

prize." The Essay was subsequently printed in several chapters in the

Merthyr Express , with the following appellatory note as a standing heading

for each chapter: " The Author of this Essay, assuming that his attempts

at deriving the origin of many place-names are imperfect, and some,

perchance, incorrect, invites criticism thereon, either private or public

Since many of the villages in the rural districts have been omitted owing to

the Author's imperfect topographical knowledge of the sequestered nooks, any

information relating to the same would be gladly received. In the multitude

of counsellors there is safety.'" It is to be regretted that very few

criticisms were received. The full meaning of Byron's words, " Critics

all are ready-made," was not

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8225) (tudalen 000_e)

|

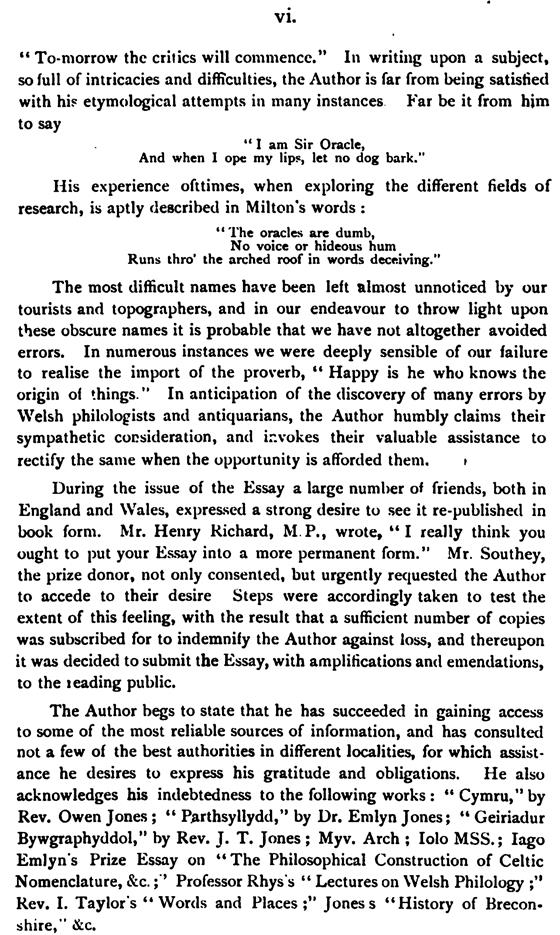

VI. "To-morrow the

critics will commence." In writing upon a subject, so full of

intricacies and difficulties, the Author is far from being satisfied with his

etymological attempts in many instances Far be it from him to say "lam

Sir Oracle, And when I ope my lips, let no dog bark." His experience

ofttimes, when exploring the different fields of research, is aptly described

in Milton's words: "The oracles are dumb, No voice or hideous hum Runs

thro' the arched roof in words deceiving." The most difficult names have

been left almost unnoticed by our tourists and topographers, and in our

endeavour to throw light upon these obscure names it is probable that we have

not altogether avoided errors. In numerous instances we were deeply sensible

of our failure to realise the import of the proverb, " Happy is he who

knows the origin of things." In anticipation of the discovery of many

errors by Welsh philologists and antiquarians, the Author humbly claims their

sympathetic consideration, and invokes their valuable assistance to rectify

the same when the opportunity is afforded them. » During the issue of the

Essay a large number of friends, both in England and Wales, expressed a

strong desire to see it re-published in book form. Mr. Henry Richard, MP.,

wrote, ** I really think you ought to put your Essay into a more permanent

form." Mr. Southey, the prize donor, not only consented, but urgently

requested the Author to accede to their desire Steps were accordingly taken

to test the extent of this feeling, with the result that a sufficient number

of copies was subscribed for to indemnify the Author against loss, and

thereupon it was decided to submit the Essay, with amplifications and

emendations, to the leading public. The Author begs to state that he has

succeeded in gaining access to some of the most reliable sources of

information, and has consulted not a few of the best authorities in different

localities, for which assistance he desires to express his gratitude and

obligations. He also acknowledges his indebtedness to the following works:

"Cymru/'by Rev. Owen Jones; " Parthsyllydd," by Dr. Emlyn

Jones; " Geiriadur Bywgraphyddol," by Rev. J. T. Jones; Myv. Arch;

Iolo MSS.; Iago Emlyn's Prize Essay on "The Philosophical Construction

of Celtic Nomenclature, &c.;"' Professor Rhys's " Lectures on

Welsh Philology;" Rev. I. Taylor's "Words and Places;" Jones s

"History of Breconshire," &c.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8226) (tudalen 000_f)

|

Vll. He has had to

consider some ingenious conjectures, far-fetched derivations, and wild

etymological dreams with great patience and caution before arriving at his

own conclusions. In a large number of examples he had no option but to

endeavour to ascertain their origin by conjecture. It was once intended to

supplement a chapter on Welsh place- names in England, but what with the

amplifications and appendices of the Essay, together with the addition of the

place-names of Monmouthshire, the dimensions assigned to the book have been

altogether occupied. Should the contents of this little volume be the means

of throwing any light on this interesting branch of Welsh literature, and

thereby enhance the vitality of the dear old language in the estimation of

the reader, the Author will be m.-.re than amply compensated. Dowlais,

January, 1887. THOMAS MORGAN.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8227) (tudalen 001)

|

THE ORIGIN OF

PLACE-NAMES IN WALES AND MONMOUTHSHIRE. INTRODUCTION. Jf T is surprising that

a subject so deeply interesting, [ and so full of historical value, should

not have ^ induced some competent Welsh scholar to explore every possible

field of research, and give the results of his etymological investigations to

the public in a permanent form. Welsh nomenclature has not had the attention

it deserves. This interesting field has been sadly neglected. Very few have

made it the ambition of their life to enter therein, and glean every possible

information necessary to throw light upon our Welsh place-names. The renowned

Lewis Morris was deeply engrossed in this branch of literature, and the

publication of his Celtic Remains would, assuredly, be an invaluable boon to

Welsh literati. Iago Emlyn's Essay which gained the prize at Carmarthen

Eisteddfod, September, 1867, is eminently calculated to be an admirable quota

rendered by the Eisteddfod to the elucidation of this sub ect. Most of our

Eisteddfodic productions are locked up in impenetrable secrecy, but this,

fortunately, has seen-the light of day. With the exception of the

above-mentioned essay our national institution has done but very little to

fill this gap in Welsh literature. Worthy attempts have been made by some

Welsh topographists to clear up the etymology of a moiety of our place-names.

Others have

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8228) (tudalen 002)

|

endeavoured to explain

their origin and meaning, but owing to their imperfect acquaintance with the

vernacular, many of their attempts have been futile and sfactory: as

Caermarthtn, the county of Merlin, Ish enchanter; Denbigh, a dwelling in the

vale; ke, the hill over the brook; Douglas is given to black-water;

Pontypridd, bridge of beauty; Tyr Bishop's tower; Llanfawr, the church of

four &c. &c. We might quote a large number of r misleading

explanations of Welsh words and that are found in English books written

evidently er than Welsh etymologists. The attempts made glishmen and others

ignorant of the language of )ld Cambria to explain Celtic names are often s

and something more. Alt macn, high rock, in ake district has been transformed

into the Old: Coniston; Bryn Huel or Hual, hill of shackles, is >elt Brown

Willy, a Cornish ridge, and Pensant sn designated Penzance. jurists' Guides

to Wales may be quite safe and )rthy in their geographical information, but

the:y of them are woefully misleading in their ogical peregrinations. Some of

their derivations deserve to be remitted to the cabinet of philocuriosities.

Out of many hundred place-names es very few of them are explained

satisfactorily Jtteers, and the most abstruse of them are left is needless to

say that Welsh philologists only can tisfactorily with purely Welsh names,

and even d it no easy task to investigate and ascertain gin of many of them,

especially those that andergone so many processes of corruption itation.

" Many Welsh appellations and local ' writes one eminent Welsh

historian, " have ) long corrupted that it would be affectation to: to

reform them." We may be allowed to give istances of names that have

already been grossly 2d: Llechwedd has been dislocated at Leckwith; Fro Nudd

has been cruelly distorted into ley; Caerau has been pulled down to Carew;

has been almost ruined in Magor; Cnwc-glas n twisted into the form of

Knucklas; Merthyr n brutally martyred at Marthrey; Tafam Yspytty m) has been

long converted into Spite Tavern; tfc

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8229) (tudalen 003)

|

. - - I Meinciau has

been minced into Minke; Gwentllwg has been changed into Wentlooge; Myddfai

has been muffled in Mothvey; Sarnau has been beaten down into Sarney, &c.

&c. Considering the rapid strides of English education in the

Principality we fear the time is not far distant when a moiety of our

mutilated Welsh place-names will be nothing less than a series of enigmatical

problems even to children of Welsh parentage. Many of them already seem to

them as a meaningless and unpronounceable jumble of letters. This process of

mutilation appears to be getting more prevalent. Our English friends, not

only do not exhibit any sign of bringing forth fruit worthy of repentance,

but they seem to persist in the error of their way in dealing with Welsh

names. Btynmawr, big hill, is pronounced with stentorian voice Brynmdr, which

signifies the hill by the sea. A complete stranger to the place, yet

conversant with the Welsh tongue, on hearing the latter pronunciation of the

name, would naturally expect he was going to inhale the salubrious sea-air;

whereas, after little enquiry, he would find himself in a tantalized mood

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8230) (tudalen 004)

|

distantly situated from

the sea. A few miles distant, at Nantybwch, the buck's brook, he might be

pardoned if he concluded from the pitiful cries of the railway officials that

there were none-to-book at that station. If he pursued his journey to

Llwydcoed, grey wood, which is pronounced by the railway men Lycod, he would

naturally conclude that the place must have been sometime noted for rats,

because Llygod is the Welsh for rats. In going through Loughor, provided his

geographical knowledge were deficient, he would imagine himself to have

reached Llotgr, which is the Welsh name for England. And a few miles lower

down he would find himself at Llanel/y, which is pronounced by certain

parties Lan-hcalthy r , where he would be induced to call his inhaling powers

into full play, positively thinking he was landed in a place famous for its

salubriousness. In North Wales he would discover the same aptitude in the art

of mispronunciation. Amid the din of the " fiery horse " he might

hear a name pronounced Aber-jeel, the suffix of which would remind him at

once of the Hindostanee for a morass, or a shallow lake; but a few minutes

talk with a villager would soon relieve him from the nightmare of this

confusion of tongues by furnishing him with the right pronunciation,

Aber-gele, an out-and-out Welsh name. At Dolgellau, which is pronounced

Dol-jelly, he might almost imagine the name to imply a doll made of jelly;

and at Llangollen, pronounced Lan-jolen, he would, both from a geographical

and etymological point of view, indulge himself in little self-congratulation

on being conveyed to a jolly place. Now he has travelled far enough to be thoroughly

convinced of the necessity of making an effort to save our local names from

the relentless hands of the foreigner before they become so distorted as to

be difficult of recognition even by Welsh etymologists. Pure Welsh names

should be left fntact those that have undergone any changes should, if

possible, be restored to their primitive form, and English equivalents or

names should be given to each and every one of them. An attempt is being made

in this book to assign English names to all the places that bear Welsh or

quasi- Welsh appellations. This was by no means an

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8231) (tudalen 005)

|

easy task. Fear and

trembling haunted us all along the line, lest we should fail to give

intelligible, short, and easily- pronounced names in English garb. Perhaps we

have sacrificed too much upon the altar of conciseness. A full, literal

translation of many of our place-names, designed for English Appellations,

would be none less than an etymological onus to others than Welshmen, so we

were naturally led to the other extreme. In order to avoid a repetition of a

literary ordeal to our dim-Cymraeg friends, we felt " 'tis better to be

brief than tedious." The enticing name Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwlltysiliogogcgogoch

has been reduced to Whitwood. It is said that a Welsh celebrity at a certain

railway station asked for a ticket to the last-named place, and the retort

given, ex cathedra, was that such a place was not in existence; whereas, if

he had only asked for a ticket to Llanfair P.G., the clipped form of the

name, he would have been supplied with it instantaneously.

Llanfair-mathafam-eit*iaf has been abbreviated to Meadton, &c. &c.

These longitudinal designations should be preserved intact, and transmitted

to the Welsh cabinet of curiosities in nomenclature, and brief English names,

such as Whitwood, Meadton, &c, should be adopted for the common purposes

of everyday life. In pursuing the study of Welsh place-names we were forcibly

reminded of Home Tooke's observation, as to " letters, like soldiers,

being very apt to desert and drop off in a long march." Contraction

increases our difficulties in endeavouring to get at the full and correct

import of words. If the American tendency to pronounce words exactly as they

are spelt and written were a universal principle, the burdens of

philologists would be considerably lessened. Such is not the case in Welsh

nomenclature. Although every Welsh letter is supposed to have its own distinct

sound, wherever placed, many of them have dropped off in long marches, and

some indeed in exceedingly short marches, and it is with great difficulty we

have induced some of them to return to their proper places in the

etymological army some, probably, never to return; hence the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8232) (tudalen 006)

|

primary form of many a

name cannot be obtained nor the true meaning ascertained. Latinized and

Anglicized forms of Welsh names considerably enhance our difficulties. M on

was transmuted to Mona, Aberconwy to Aberconovium, Abergafeni to

Abergavenniutn, Aberogwr to Ogtnore, Nedd to Ntdium, Coed-dy to Coyty,

Talyfan to Talavan, Sili to Sully, Llys-y-Fro-Nudd to Lisworney, Llanyffydd

to Lamphey y Llandeg to Lanteague, Gwynfa to Wenvoe, &c. Our names, like

our fathers, were mercilessly treated by our foreign invaders. Hybridism is

another element that renders Welsh nomenclature exceedingly difficult and

perplexing. Different nations visited our shores, and played sad havoc with

our local names, especially those having gutterals in them. " We have

names of such barbarous origin," writes one, " compounded one-half

of one language and the other of another, that it is impossible to fix a

criterion how they ought to be spelt." The Flemish colony in

Pembrokeshire, in the reign of Henry L f and the Norman settlement in the

south of Glamorgan, in the nth century, are chiefly responsible for this

etymological jumble. The Norman Conquest affected the English language more

than anything that happened either before or after it, but very little of its

effect is found in the Welsh, except in place-names. These hybrid names,

albeit, are full of historical value, because they give us geographical clues

to the inroads and settlements of these foreign invaders. Alluding to the

desirability of getting a correct definition of an effete nomenclature, one

writer remarks, " It must be borne in mind that the nomenclature of our

country greatly explains the early history of Britain from the time of the

first colonists, the settlement of the Druids, and their subsequent power

both in civil

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8233) (tudalen 007)

|

and religious matters,

and its continuance down to the age of Suetonius, and later still, as the old

superstition was not quite eradicated for many ages afterwards. Their

mythology has left its marks on numerous places, even where their lithonic

structures have been demolished." After all it is, as Defoe ironically

remarks in his " True-born Englishmen," With easy pains you may

distinguish Your Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman-English. Personal names enter very

largely into Welsh names of places. The first place-name we have on record

was formed after this fashion, " And he (Cain) builded a city, and

called the name of the city after the name of his son, Enoch." Gen. iv.,

17. These personal names are invariably in the vernacular affixed to words,

more or less, of a descriptive character, as T r dales; tre y the descriptive

first, then comes the personal, Laics; Porthmadog, porth, the descriptive,

then follows the name Madog. The majority of names beginning with Llan belong

to this section. In Saxon and Norse names the reverse of this is the general

rule. The descriptive part of the name comes last, preceded by a personal or

common name, such as Tenby; Ten, a mutation of Dane, and by y the Norse for a

dwelling, hence the dwelling-place of the Danes. Walton, Walter's town;

Williamston, William's town; Gomfreston, Gomfre's town; &c. It was

customary in olden times in Wales for men to take their names from the places

where they were born or resided, as Pennant, Mostyn, &c, and oftentimes

the case was reversed. Brecon was called after Brychan; Cardigan after

Ceredig; Merioneth after Meirion; Eaeyrnion after Edeytn; Dogfeilit after Dog

fad; Merfhyr Tydfil a'ter Tydfil, Brychan's daughter, &c. The names of

popular Welsh saints have been bestowed so liberally on the Llanau as to

occasion no little confusion. A similar practise prevails in the United State

from respect to their popular Presidents. The Rev. Isaac Taylor tells us that

no less than 169 places bear the name of Washington, 86 that of Jefferson,

132 that of Jackson, 71 that of Munroe, and 62 that of Harrison. Hagiology

has left a deep and wide impress upon our nomenclature. St. Mary's name has

been bestowed upon upwards of 150 churches and chapels in the Welsh sees,

that of St. Michael's upon about 100, and that of St. David's upon 60 or 70.

A great number of our place-names describe graphically the physical features

of the country. Mountains, hills, and mounds, rocks and cliffs, glens and

combes, moors and woods, rivers and brooks, all contribute their quota to the

treasury of our nomenclature. Many of them are traced to local traditions

which rarely command more than a local circulation. In making enquiries at

different localities we were more than amused to observe the prevalent

tendency of the inhabitants to trace the origin of their local names to

traditionary sources. The philologist is often superseded by the

traditionist. Graphic and descriptive names are frequently explained from a

traditional stand-point. Machynllaithdi name descriptive of the geographical

position of the place was very dogmatically referred by one to an ancient

legend concerning some " mochyn-yn-y-llaeth" the pig in the milk.

Trotdrhiwfuwch, explained another, means Troed-rhyw-fuwch, the foot of some

cow, in allusion to a local tradition about a cow that had gone astray.

Manorbier, the third

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8234) (tudalen 008)

|

8 opines, has reference

to a severe conflict between a man and a bear in times gone by. Wrexham, says

the fourth, is obviously a corruption of Gwraig Sam, Sam's wife. Crymmych,

the fifth avers, is *i transposition of " Ychyn crymu," the ox

stooping, &c, &c. The reader may take these fanciful and untenable

derivations for their worth as evidences of the tenacity with which some

people hold to their folk-lore. The majority of our place-names, as might

have been expected, have been derived from pure Celtic sources. Bishop Percy

says that " in England, although the names of the towns and villages are

almost universally of Anglo-Saxon derivation, yet hills, forests, rivers,

&c, have generally preserved their old Celtic names." In

illustrating the prevalence of Celtic names in Britain, the Rev. Isaac Taylor

writes: " Throughout the whole island almost every river-name is Celtic,

most of the shire-names contain Celtic roots, and a fair sprinkling of names

of hills, valleys, and fortresses, bear witness that the Celt was the

aboriginal possessor of the soil; while in the border counties of Salop,

Hereford, Gloucester, Dorset, Somerset, and Devon, and in the mountain fastnesses

of Derbyshire and Cumberland, not only are the names of the great natural

features of the country derived from the Celtic speech, but we find

occasional village-names, with the prefixes Ian and tre, interspersed among

the Saxon patronymics." What is true of England is pre-eminently true of

Wales, where the great bulk of place-names are distinctly Cymric, everywhere

thrusting themselves upon our notice as standing proofs of the vitality of

the language of our progenitors. Many are the false prophets that have

sarcastically declared, from time to time, that the days of the Welsh

language have been numbered. We might observe, en passant, that it contains

more vitality than the Gaelic. The latter is only talked in some parts of

Scotland, but the Cymric is the domestic language of the vast majority of the

Welsh people, wheresoever situated. It is calculated that more than a million

of the inhabitants of Wales and Monmouthshire use the vernacular in domestic

conversation, in literary and newspaper reading, and in religious exercises.

What with the continuation of the Cymric in the curriculum of our

Universities and Theological Colleges, its introduction as a specific subject

into our public elementary schools, the ardency and faithfulness with which

it is taught in our Sunday schools from Caergybi to Caerdydd, the

ever-increasing attention paid and the new life infused into it by various

institutions, as the Eisteddfod, the Honourable Society of Cymrodorion, the

Society for Utilising the Welsh language, and the proverbial clannishness of

the Kymry; looking retrospectively and prospectively our conviction is that

the dear old language contains germs of a long and healthy life, and when it

shall cease to be a vernacular much of its intrinsic value and glory will be

preserved in its local names.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8235) (tudalen 009)

|

PREFIXES AND SUFFIXES.

We shall now deal briefly with the chief prefixes and suffixes that occur so

frequently as components in names of places in Wales, in order to avoid

entering largely into details in tracing their origin in the subsequent

pages. Many of them contain the geographical and historical clues to a large

number of names, and since they enter so extensively into Welsh nomenclature,

we think it essential to offer a few explanatory notes thereon. Aber means

the mouth of a river, a particular point at which the lesser water discharges

itself into the greater. In the old Welsh it is spelt apcr, and Professor

Rhys, Oxford, derives it from the root ber, the Celtic equivalent of fer, in

Lat. fer-o t Greek phero % English bear. It originally meant a volume of

water which a river bears or brings into the sea, or into another river; but

it is now generally used to denote an estuary, the mouth of a river. Some

think it is cognate with the Irish inver: Inverary, mouth of the Airy; and

that inver and aber are suitable test-words in discriminating between the two

chief branches of the Celts. Mr.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8236) (tudalen 010)

|

IO Taylor says that "if we

draw a line across the map from a point a little south of Inverary to one a

little north of Aberdeen we shall find (with very few exceptions) the invers

lie to the north-west of the line, and the abers to the south-east of

it." The Welsh form occurs repeatedly in Brittany: Abe*vrack, Avranches.

The Norman French haver is identified with the Welsh abet. In the lowlands of

Scotland we find it in Aberdeen, Abernethy, Abercorn, Abertay, &c, and in

England we find it in Aberford, Berwick, &c. Wherever found in Welsh

place-names it is almost invariably followed by a proper or common name,

indicating a brook or river flowing into another river, or the sea. Ach is a

Celtic derivative particle denoting water. Agh in Ireland means a ford, och

signifies the same in Scotland, and the Latin aqua has the same meaning. The

Sanscrit ux, uks, means to water. We find many brooks and rivers called Clydach,

sheltering water; Achddu means black water, amdgwyach is a general term for

several species of water-fowl. Afon, a river, comes probably from the Celtic

awon, the moving water. In the Manx language it is written Aon, in the Gaelic

abhainn (pronounced avain), and in the Itinerary of Antonius it is Abona. It

is found in English in the form of Avon, which, in the opinion of Professor

Rhys, appears to have been entitled to a v as early as the time of Tacitus.

This form occasions redundancy in the English language. To say " Bristol

is on the river Avon " is tantamount to saying " Bristol is on the

river river." Afon, a common name, has become a proper name in England,

but in Wales it is the generic term for a river. Ar signifies " ploughed

land." Arddu, to plough. The Greek word for a plough is arotron, the

Latin is ardtrum, the Norse is ardr, the Irish is arathar, and the Welsh is

aradr. The English " harrow " was originally a rude instrument

drawn over ploughed land to level it and break the clods, and to cover seed

when sown. Ploughing and reaping are called " earing and harvest."

Compare Gen. xlv., 6.; Ex. xxxiv.,-21.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8237) (tudalen 011)

|

II When at is used as a

suffix it generally has an agricultural signification, but when used as a

prefix it is a preposition, meaning on, upon: Ardwr, on the water; Argoed, on

or above a wood. Bettws forms a part of a large number of our local names.

Some think it is a Welshified form of the Latin beatus, blessed, and that it

refers to the religious institutions of St. Beuno. Others derive it from

abbatis, an appendage to a monastery or an abbey, taking it as one of the few

Latin words which found a permanent place in the Welsh language. It is

derived by some from bod-cwys, a place of shelter, but the most prevalent

opinion is that the word is a Welshified form of bead-house, an

ecclesiastical term signifying a hospital or alms-house, where the poor

prayed for their founders and benefactors. " Beads are used by Roman

Catholics to keep them right as to the number of their prayers, one bead of

their rosary being dropped every time a prayer is said; - hence the

transference of the name from that which is counted (the prayers) to that which

is used to count them. The old phrase to ' bid one's beads' means to say

one's prayers (Imp. Diet)." In a recent communication to us, Professor

Rhys says " Bettws would be phonologically accounted for exactly by

supposing it to be the English bed-Ms or house of prayer, but if that origin

be the correct one to assume there is the historical difficulty: where is

there any account of this institution bearing an English name? " There

is the rub. We cannot find a single instance of the name being perpetuated in

England. The Rev. J. Davies, F.S.A., Pandy, is of opinion that "Bettws

was never an institution properly* speaking, and it never existed as a

distinct religious house, but undoubtedly it did exist in some instances as a

cell in connection with large Abbeys. Soon after the principal Abbeys had

been founded in this country, and their fame as seats of piety and learning

had spread far and wide, pilgrims began to flock to them, many of whom had

long distances to travel, on account of which houses of prayer, called

Bead-houses, were erected at long intervals along their

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8238) (tudalen 012)

|

12 course into which the

' wearied pilgrims ' entered to offer prayers on their way to and from the

Abbey. I believe we never have a Bead-house (Bettws) but on the way to an

Abbey. When the Abbeys were suppressed, most of these Bead-houses fell into

ruin, as a matter of course, while a few of them may have developed into

parish Churches and Chapels of Ease, after the Reformation. I do not think it

has a Welsh origin, for the reason that the thing itself was imported from

Normandy, and I am of opinion that Bettws as a place- name was not in

existence prior to the Norman Survey." Blaen means extremity, the top of

anything. It is frequently used as a prefix in the names of places that are

situated at the extreme end of a valley or near the sources of brooks and

rivers. Blaenau afonydd, the sources of rivers. Dwfry blaenau, water or

stream from the height. Bod originally meant a lord's residence. Having fixed

upon a certain spot of land, he would build a dwelling-house thereon, which

was called bod, and the name of the builder or owner was added to distinguish

it from other dwelling-houses, hence we have Bodowain, Bodedeyrn, &c. He

had two residences _yr Hafod, the summer residence, and Gauafod, the winter

residence. But in course of time bod was used to designate any house or

dwelling-place. Compare the English " abode." Bron means a round

protuberance, and is equivalent to the English breast. In place-names it signifies

the breast of a hill. Ar frest y mynydd, is a very common expression, meaning

on the breast of the mountain. Bryn seems to be a compound of bre, a

mountain, and the diminutive yn; hence breyn, afterwards contracted into

bryn, a small mountain, a hill. It enters largely into Welsh place-names, and

we find it also Anglicized in Breandown, a high ridge near Weston-

super-Mare; Brendon, a part of the great ridge of Exmoor; Brinsop, Hereford,

&c. Bwlch signifies a break or breach. It is generally found in names of

places where there is a narrow pass in the mountains.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8239) (tudalen 013)

|

13 Caer is one of our

enchorial names for a wall or mound for defence, the wall of a city or

castle, a fortress. Perhaps the root is cau, to shut up, to fence, to enclose

with a hedge. Cae means a field enclosed with hedges. Caerau were the most

ancient military earthworks in the Principality, and when the Britons began

to build cities they surrounded them by a fortified wall called caer. The

city of Chester is still popularly called Caer, from the ancient wall that

has encircled it for ages. Chester a Saxonized form of the Latin castrum, a

fort, and one of the six words recognised as directly inherited from the

Roman invaders is a common prefix and suffix in English place-names; as

Colchester, Manchester, Chesterford, Chesterton. In the Anglian and Danish

districts we find " Chester " is replaced by "caster"; as

Doncaster, Lancaster, &c, but both forms are allied to castrum, which is

a Latinization of the Celtic caer. As the Latin castrum will always be an

etymological souvenir to future generations of the Roman incursions, and the

havoc they committed here ere " Britannia ruled the waves," even so

the Celtic word caer, which is found in so many Welsh and a few English

place-names, will ever be an historical finger- post, pointing to the

necessity which was laid upon our forefathers to defend themselves against

foreign bands of invaders. The word is also a standing proof in England that

the dominion of the ancient Kymry was sometimes considerably more extensive

than that of little Wales. If the reader will be so fortunate as to find a

map of England which was published in the time of Ella, the first Bretwalda

of the Saxon race, the recurrent caer would make him almost imagine he was

perusing the map of Wales. There he would find Caer-legion, Chester, which is

still called Caerlleon; Caer-Badon, Bath; Caer-Glou, Gloucester; Caer-Ebrawe,

Eboracum of the Romans, and the Saxon York; and Caer-Lundcne, London, &c.

In course of time the vowel e was elided, hence we have such examples as

Carmarthen, Cardiff, Carlisle, Carsey, Carsop, Pencarow (Pen caerau), Carew,

&c. Carn, Carnedd, or Cairn, means a heap of stones. These cairns or

tumuli are found in large numbers in

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8240) (tudalen 014)

|

Wales. They were,

according to some, either family cemeteries or monuments raised to

commemorate the relics of a number of heroes who fell in defence of their

country. But others are inclined to think they were thrown, as tokens of

disgrace, over executed malefactors. Dr. Owen Pugh says " The

carneddau and the tumuli of earth were the common monuments that the ancient

Britons erected in honour of their great men. Which of the two kinds was

probably determined by the circumstance of the country being stony or

otherwise. These modes of interment continued in use many years after the

introduction of Christianity; but when the custom of burying in churches

became general, the former ways were not only disused, but condemned as fit

only for the great criminals. When the carncdd was considered as the

honourable tomb of a warrior, every passenger threw his additional stone out

of reverence to his memory. When this heap came to be disgraced by being the

mark where the guilty was liid, the custom for everyone that passed to fling

his stone still continued, but nowise a token of detestation. "

Professor Rhys, in his " Celtic Britain," gives a graphic description

of the removal of one of these cairns in the vicinity of Mold, in 1832.

" It was believed," he writes, " in the country around to be

haunted by a spectre in gold armour, and when more than 300 loads of stones

had been carted away the workmen came to the skeleton of a tall and powerful

man placed at full length. He had been laid there clad in a finely- wrought

corslet of gold, with a lining of bronze: the former was found to be a thin

plate of the precious metal, measuring three feet seven inches long by eight

inches wide. Near at hand were discovered 300 amber beads and traces of

something made of iron, together with an urn full of ashes, and standing

about three yards from the skeleton. The work on the corslet is believed to

have been foreign, and is termed Etruscan by Prof. Boyd Dawkins. The burial

belongs to an age when cremation was not entirely obsolete in this country,

and we should probably not be wrong in attributing it to the time of the

Roman occupation. On the whole, the duty of commemorating the dead

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8241) (tudalen 015)

|

15 among the Celts may

be supposed to have devolved on the bards, to whom we are probably indebted

for the seventy or more triplets devoted to this object and preservei in a

Welsh manuscript of the twelfth century. The last of them, which, remarkably

enough, has to do with a grave in this same district of Mold, runs as

follows, when freely rendered into English: Whose is the grave in the great

glade? Proud was his hand on his blade There Beli the giant is laid."

Castell, frequently contracted into cas, is the Welsh for a castle, a

fortified residence. It is difficult to ascertain the exact time when castles

were first introduced into Wales. The Romans probably began to erect

fortresses in the territories conquered by them, and the Saxons followed

their example; but strong castles of defence were comparatively few here ere

the commencement of the Norman Conquest. Feudalism gave rise to castles in

the sense of fortified residences, and it is from the advent of the Normans

to our land we must date the castle as an institution. A large number was

also erected during the reign of Edward III. and his immediate successors.

" That old fortress," said Mr. Gladstone, pointing with his stick

to the remains of Hawarden Castle, " is one of the emblems of the

difficulty the English had in governing the Welsh in former times. They had

to plant their strongholds all along the Welsh border." Cefn, in names

of places, means a high ridge. It is but natural that this prefix should be

applied to so many places in mountainous Wales. The Chevin Hills in

Yorkshire, and Cevennes in France, derive their names from the same root. Cil

implies a sequestered place, a place of retreat. Cil haul means the shade or

where the sun does not shine. Cil y llygad, the corner of the eye. In Ireland

it is spelt kil (the c being changed to k) signifying a church, and is found

in no less than 1,400 names, and in \ many in Scotland. Kilkenny, church of

Kenny; Xilpatrick, church of Patrick; Kilmore (Cilmaivr), the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8242) (tudalen 016)

|

i6 great church. Gilmor

is still a surname in the Scottish lowlands, and we find G'lmorton in

Leicester. We find the root in cilio, to retreat, to go away. Cilfach, a

place to retreat to, a creak, a nook. Some Welsh historians think that cil is

a local memorial of those Irish missionaries, who, about the 5th century,

visited the shores of Wales for evangelistic purposes, and founded churches

in the most quiet and sequestered spots they could find. Clyd means

sheltering, warm, comfortable. Lie clyd y a warm, comfortable place. We have

it in different forms in Clydach, Clydlyn, Clyder, Clyde, Strathclud,

Clodock. Clyn signifies a place covered with brakes, Clyn o eithin, a furze

brake. Cnwc literally means a bump, a swelling: Cnwc y gwegil, the back part

of the skull; but its geographical signification is a knoll or mound. We find

it corrupted in a few Welsh names, Knucklas (Cnwc-glas), &c, and in Irish

names, Knockglass (Cnwc-glas), Knockmoy (Cnwc-tnai), Knockaderry

(Cnwc-y-deri), &c , and in England we have Nocton, Nacton, Knockin,

Knook,&c. Coed is the Welsh for wood, trees. In remote times the summits

of Cambria's hills were covered with wood, which accounts for the word coed

being still applied to barren and hilly districts. Craig, a high rock or

crag, and sometimes it is applied to a steep, woody eminence. It takes the

form of carraig or carrick in Ireland; Carrigafoyle (Craigyfoel), the barren

rock; Carrickfergus, the rock where Fergus was drowned; and in England we

find it in Crick, Cricklade, &c. Croes means a cross. Croes-ffordd, a

crossway. The word evidently points to the Roman epoch, and also to the

ancient Welsh custom of burying malefactors near the cross roads.

Croes-feini, stone-crosses, in the time of Howell the Good, were used

principally to mark land property, and sometimes, when placed in hedges, to

caution travellers not to cross the fields. Some of them, with the names of

the primitive British

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8243) (tudalen 017)

|

17 saints inscribed upon

them, were placed by the roadside in commemoration of the blessed fact that

the Gospel had been preached there. Crug means a heap, a mound. Crug o

gerryg, a heap of stones. It appears that the Britons held their bardic and

judicial gorseddau or assemblies on these mounds, and hence " crug"

and " gorsedd," according to Dr. Owen Pughe, are sometimes used as

synonymous terms. " Crug " is a frequent component in Welsh names,

and we find it Anglicized in Crich

(derby), Creach (Somerset), &c. Cwm denotes a low place enclosed with

hills. It has a large place in Welsh nomenclature, and it often occurs in

English local names, especially in the western counties. In Devonshire the

Saxonized form comb or combe meet us frequently: Wide-comb, W r el-comb,

Ilfra-combe, Babba-comb, Burles-comb, Challa-comb, Hac-comb, Para-comb,

Yarns-comb, &c. In Somerset it is more plentiful than in any other

English county: we have Nettle-comb, Od-comb, Timber-comb, Charls-comb,

Wid-comb, Moncton-comb, Comb-hay, Cros-comb, Wins-combe, &c. We find

King-combe, Rat-combe, Bos-comb, &c, in Dorset. Cumberland, a Celtic

county, is derived by some from the combes with which it abounds. So writes

Anderson, a Cumberland poet, of his native county: There's Cumwhitton,

Cumwhinton, Cumranton, Cumrangan, Cumrew, and Cumcatch, And many mair Cums i'

the county, But cone with Cumdivock can match. Cymmer means a junction or

confluence, and is frequently applied to places situated near the junction of

two or more rivers. The root is related to aber (vide abet). Din is an

ancient Welsh word for a fortified hill, a camp, from which we have our

dinas, a fortified town or city, and probably the English denizen. Our cities

were once surrounded by fortified walls, like Chester, on account of which

every one of them was denominated dinas. Proffessor Rhys groups the Welsh din

with the Irish dun, the Anglo-Saxon tun, and the English town.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8244) (tudalen 018)

|

i8 The dunum, dinum, and

dinium of the Romans are probably allied with it. The English suffix bury is

closely related to it in meaning. Very few Welsh place-names have the

termination burgh, bury, or borough. The root is almost an English monopoly.

Home Took says that 44 a burgh or borough formerly meant a fortified town."

In the ' Encyclopaedia Britannica" we find the following exposition of

the word: Bourgignons or Burgundians, one of the nations who over-ran

the Roman Empire, and settled in Gaul. They were of great stature and very

warlike, for which reason the Emperor Valentinian the Great engaged them

against the Germans. They lived in tents, which were close to each other,

that they might the more readily unite in arms on any unforeseen attack.

These conjunctions of tents they called burghs, and they were to them what

towns are to us." It is supposed that the Burgundians introduced the

word to the Germans, and they, again, left it in England as a trace of their

settlement here. Dol signifies a meadow. Dol-dir, meadow-land. We find it in

many of our place-names, and also in various forms in Arundel, Kendal (Pen

-ddol), Annandale, Dalkeith, Dalrymple, Dovedale, &c. The word is found

in names of places situate in valleys all over Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany.

Dwfr is the modern Welsh for water. It is frequently spelt dwr: Cwmdwr, the

watervale. In English it has suffered much from phonetic decay: Derwent,

Dover, Appledore, Durham, Dore, Thur, Durra, &c. It is also found in

European names: Dordogne, Adour, Durbian, Durbach, Douron, Dwerna, Oder,

&c. (" Words and Places/' p. 200). It may be compared with the

Cornish dour, the Gaelic and Irish dur % and dobhar, pronounced doar, and the

Greek udor, all derived probably from the Celtic dubr. Dyffryn is popularly

derived from dwfr, water, and hynt, a way, a course; literally a

water-course, or a vale through which a river takes its course. In the

ancient Welsh laws the word dyffrynt is used to denote a river. 44 Ynysoedd

yn nyffrynt," islands in a river. It may be

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8245) (tudalen 019)

|

19 a compound of

dwfr-bryn, signifying a hilly place through which water flows. Gallt means an

ascent, a slope. Gallt o goed, a woody slope or eminence. In North Wales it

signifies "a steep hill," and in South Wales "a coppice of

wood." Garth originally meant a buttress, an inclosure. The Norse garth,

the Persian gird, and the Anglo-Saxon yard, denote a place girded round, or

guarded. Garden is a place fenced round for special cultivation. Buarth, from

bu, kine, and garth, a small inclosure, was situated on a hill in perilous

times. Lluarth from llu, a legion, and ga>th, inclosure, means an

entrenchment on a hill. In course of time the word became to signify a ridge,

a hill, a rising eminence, a promontory. Gelli-CcM means a wood, a copse. The

simpler form cell meant a grove, and the Irish coill bears an identical

meaning. Cell ysgaw, an elder grove. The aborigines of Scotland were called

Cceoilldaoin, which meant " the people of the wood," which name was

changed by the Romans to Caledonia. A great number of places have received

their names from species of trees, as Clynog, Pantycelyn, Clyn eiddw, &c.

Glan means brink, side, shore. Glan yr afon, the river side, or the bank of

the river. Glan y tnor, the sea shore. The word is generally prefixed to

river-names, as Glan-Conwy, Glan Taf, &c. Glas is used to denote blue,

azure, green. When applied to water it signifies blue Dulas, black-blue;

but when applied to land it means green; Caeglas, green field. The word is

supposed by some Cymric scholars to be allied to the Greek glaukos, both

expressing the same colours those of the sea. Glaucus was a seadeity. Glyn

implies a vale narrower but deeper than a dyffryn, through which a river

flows. It generally precedes the name of a river that flows through a vale,

as Glyn Ceiriog, Glyn Dyfrdwy, &c. From the same root we have the Gaelic

" gleann " and the Anglo-Saxon "glen," both expressing a

small valley.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8246) (tudalen 020)

|

20 Gwydd signifies wood,

from which we have gwyddel, which means a brake or bush. Tir gwyddtlawg, land

overrun with brambles. Gwyddel is also the Welsh for Irishman, and some view

the few place-names that contain the word only as ethnological evidences of

the temporary sojourn of the Gaels in Wales. Some, evidently, have the latter

signification, but the majority of them have no reference to Irishmen, as

Gwyddelwern, &c. Hafod is a compound of haf and bod, signifying a summer

house. The ancient farmers had their summer dairy-houses, and in that season

they resorted thither, as the farmers in the Swiss Alps do to their Sennes.

The hafod consisted of a long, low room, with a hole at one end to emit the

smoke from the fire which was made beneath. Its stools were stones, and beds

were made of hay ranged along the sides. Llan is identified with nearly all

the names of parish churches in Wales, from which an exceedingly large number

of places take their names. It has been said that " England is

pre-eminently the land of hedges and inclosures." The terminations, ton,

ham, worth, stoke, fold, garth, park, burgh, bury, brough, burrow, almost

invariably convey the notion of inclosure and protection. The Welsh prefix

Llan, which signifies a sacred inclosure, probably suggested the idea to the

Saxon colonists. We find the word in perllan, orchard; gwinllan, vineyard;

corlan, sheep-yard, in Welsh place- names it generally means a church,

probably including the church-yard. Mynedfrllan means'* going to

church." The British saints, having been deprived of their possessions

by the powerful and ever-increasing foreigners and invaders, retired to the

most solitary places in the country to live a wholly religious life, and

founded churches which will bear their names as long as hagiology will remain

a part of Welsh history. Judging from the number of churches dedicated to the

saints, it appears that the most popular among them were St. Mary, St.

Michael, and St. David, the patron saint of Wales. It is needless to say that

the first two never founded churches, although we find that

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8247) (tudalen 021)

|

21 26 churches in the

see of Bangor; 27 in the see of St. Asaph; 59 in the see of St. David's; and

a few in the see of Llandaff; in all about 150 churches and chapels have been

dedicated to St. Mary, and to St. Michael: 48 in the see of St. David's; 8 in

the see of St. Asaph; 16 in the see of Bangor; 20 in the see of Llandaff; and

a few in the see of Hereford, making a total of nearly 100. Next comes St.

David. We find that 42 sacred edifices bear his name in the see of St.

David's; 8 in the see of Llandaff; and a few in the see of Hereford. Many

churches were also named from their contiguity to water, as well as to -other

objects: Llanwrtyd (Llan- wrth-y-rhyd), the church by the ford; Llanddf % the

church on the Taff, &c. The llan, a public house, and a few cottages,

formed the nucleus of the majority of our rural villages and parishes, and

when the village or parish became worthy of an appellation, the name of the

llan was almost invariably applied to them. The word sant, saint, never

became a popular term in Wales. We have simply the llan and the unadorned

name of the saint to whom it was dedicated, not Llansantddewi, St. David's

church, but Llanddcwi, David's church. When several churches are dedicated to

the same saint some differential words are added, and so we have those long

names which arouse the curiosity of our English friends, and often supply a

healthy exercise to their risible faculties, such as Llanfair-Mathafarn-

eithafy &c. For the sake of euphony and brevity we have, in many of our

English equivalents, omitted the word llan % and have given the names of the

saints only, except when they are translatable. When differential words are

added to the hagiological names, as Penybryn, Helygen, &c, we have

thought it advisable to omit the ecclesiastical term, and give the mundane

portion of the name only as an English quasi-equivalent. For instance,

Llandewi-Aberarth, omitting St. David's, and render Aberarth into an intelligible

English name. We find the word llan in many place-names in England, in the

Cymric part of Scotland, as Lanark, Lanrick, &c, and in Brittany, as

Langeac, Lannion, Lanoe, &c. It is

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8248) (tudalen 022)

|

22 now superseded by the

word egluys, church, in most parts of the Principality. Llech, a flat stone,

a flag, refers probably to the Druidical circle stones. Notice should be made

of the difference between Cromlech and Cistfaen. The former was a sepulchral

monument and always above ground, and the latter was the coffin, concealed

either by a tumulus of earth or stones. The cromlech generally had a cistfaen

under it. The English league is probably derived from this word, a

"league*' was a measure of distance marked by a stone standing on end.

Llwch is the ancient Welsh for an inlet of water, a lake. It corresponds to

the Scotch lock, the Irish lough, and the English lake. Loch Leven smooth

lake. Llwyn in its primary' sense means a bush, but it is frequently used to

denote a grove. Llys originally meant a royal court, a palace. Llysdin, a

city where a prince's court was kept, but it is now the common appellation

for a court. Maenor originally meant a division of land marked by stones,

from maen, a stone; hence it became to signify a district, a manor. The

macn-hir, long-stone monument, is considered by Professor Rhys to be as old

as the cromlech, but not so imposing and costly. Crots-faen. (See Crccs).

Maes, an open field, in contradistinction to cat, an enclosed field. It is

sometimes used as a military term signifying a battle-field. Cad at faes is a

pitched battle, and colli y macs is to lose the battle. In the majority of

names where this component occurs we may fairly infer that a battle has been

fought there. Mai means an open, beautiful plain. It is also the Welsh for

May, the month when nature induces one to go out to the open fields to view

her gems of beauty f Moel when used as a substantive signifies a bald,

conical hill. Dynpenfoel, a bald-headed man. In olden times it was used as a

surname. Hywel Foel, Howell, the bald-headed. It is derived by some from the

Celtic root mull y a bald head. Moylisker (Westmoreland) is a

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8249) (tudalen 023)

|

2 3 corrupted form of

Moel-esgair, bare ridge. Malvern is supposed to be a contraction of

Moel-y-fartt, the hill of judgment. In Ireland we find it corrupted to moyle:

Kilmoyle, bald church; Dinmoyle, bald fort. Mynydd is the popular Welsh word

for mountain, from mwn, what rises considerably above the surface of the

surrounding land. Myn'd t fynydd or fyny means going upwards. Nant in its

primary sense signified a ravine, a dingle; but now it is mostly used to

denote a brook, a streamlet. The root enters largely into Welsh nomenclature,

and it is also found in many place-names in the region of the High Alps.

Nannau and Nanney are plural forms of it, omitting t, and adding the plural

termination au. Pant means a low place, a hollow. It is considerably less

than a cwm or dyffryn, combe or valley, being somewhat similar to a glen.

Parc is an inclosure, equivalent to cae, a piece of land enclosed with

hedges. It is used in the latter sense in the south-west counties. Parth

comes from the same root, which means a division of land. Parthau Cytnru, the

divisions of Wales. The English " park " is a derivative, which has

a more extensive meaning. Pen in geographical names means the highest part or

the extreme end, as of a mountain or a field, or a meadow. We find it intact

in names of places in Cornwall, as Penzance (saint's head), Penrhyn

(headland), and in the north of England we have Penrith; but in its native

country the consonant n has been omitted in many instances, and m

substituted, as in Pembroke, Pembrey, &c. Ben, a mountain, enters largely

into the composition of place-names in Scotland, especially in the Highlands,

as Ben-more, (Penmawr), great mountain, &c. Cen or cenn is another Gaelic

form, signifying the same as pen and ben. Cantyre (Pentir), headland; Kenmore

(Penmawr), great mountain; Kinloch (Penllwch), head of the lake. In South

Scotland ben is replaced by pen, the Cymric form, as Pencraig, the top of the

rock; Penpont, the end of the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8250) (tudalen 024)

|

24 bridge, &c. We

find it also in European names pointing out the earlier settlements of the

Celtic race, as Pennine, Apennines, Penne, Penmark, &c. Pont is generally

derived from the Latin pons,pontis f a bridge. The monks were great

bridge-builders, and it is supposed that they introduced the word to us.

Pontage is a duty paid for repairing bridges. The Roman pontiff was so called

because the first bridge over the Tiber was constructed and consecrated by

the high priest. Pontefract is a pure Latin name, from pons, a bridge, and

frangerc, to break, signifying a broken bridge, so called from the bridge

breaking down when William, Archbishop of York, was passing over. Porth is

referred by some to the Latin porta, a passage-way, a gate, an opening. Rhiw

is the Welsh for ascent, acclivity, slope. It has an analogous meaning to

Eppynt, the name of a chain of mountains in Breconshire, probably from eb, an

issuing out, and hynt, a way, a course, signifying a way rising abruptly.

Hyntio means to set off abruptly. Rhos means a moor. Some think the Latin rus

is a cognate word, signifying undrained moorland. The Cymric rhos is

frequently confused with the Gaelic ros, which signifies a promontory. Ross,

the name of a town in Herefordshire, is probably a corruption of the former.

Rhyd in its primary sense means a ford, but its secondary meaning a stream,

is frequently given to it. Rhyd-erwin means the rough, dangerous ford,

whereas Rhydfclin designates a stream of water that turns a mill. Sakn is the

Welsh for the old Roman paved road, and wherever it occurs one may almost

certainly find traces of a Roman road. Unlike almost every other road the

Roman strata was distinguished for its straightness. It ran from fortress to

fortress, as straight as an arrow course, in order to facilitate communications

between those who were stationed in the chief strategic positions of Britain.

It was generally about 15 feet wide, the sides being fenced by huge stones,

and the middle well paved. Remains of it are

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8251) (tudalen 025)

|

25 still discernible in

many parts of the Principality, such as the neighbourhood of Caersws,

Montgomery; Gaer, Brecon; Neath, Glamorgan; and many other places. Tal when

applied to places means end, but when applied to persons it denotes front.

Taliesin means radiant front or luminous head, but Talybont signifies the end

of the bridge. From this comes the English tall. Ton originally meant a piece

of unploughed or uncultivated land, perhaps from twn, which implies a piece

of land taken for the purpose of cultivation. It is used in Glamorgan to

denote a green. sward. Tref was the primitive Welsh appellative for a

homestead, a dwelling-house. Myned tua thref going home, is still a common

expression in South Wales. In course of time the term was extended to

indicate a group of homesteads. Having built a house for himself the lord

would proceed to build dwellings for his people and his cattle, and these

formed what was called tref. The word gradually became to be applied to an

aggregate of houses, hence the reason why it is used so frequently in village

as well as in town -names. The root is widely distributed over Britain and

Europe. The Norse by, the Danish thorpe, the German dorf, and the English ham

and ton may be considered as its equivalents. It is spelt treu in Domesday

Book, hence we have Treuddyn for Treddyn. - Hendref forms the names of many

old mansions, and is synonymous with the English Aldham and Oldham. Hydref

(October) was the harvest season the time to gather the produce of the

fields to the barns, and leave the hafod, summer-house, to spend the winter

months in the hendref, the older establishment. The original meaning of

cantref (canton or hundred) is supposed to have been a hundred homesteads.

Troed is the Welsh for foot, base. The Irish traig signifies the same, both

of which, Professor Rhys thinks, are of the same origin as the Greek trecho,

" I run." The English tread means to set the foot. The word is

frequently applied to places situated at the foot of a moun-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8252) (tudalen 026)

|

26 tain. The Welsh

Troedyrhiw and the Italian pie di monte are almost synonymous terms. Ty

generally means a house, a dwelling-place, but in Welsh nomenclature it is

occasionally used to denote a church or place of worship, as. Ty Ddewi, St.

David's. The house of God is considered by many as equivalent to the church

of God. Ty has an inferior meaning to bod; the latter was the residence of a

superior, and the former is of a later date, signifying an ordinary house, a

cottage. W r Y Gwy is an obsolete Celtic word for water, mostly used as a

suffix in river-names, as Elwy, Tawy; and sometimes "as a prefix, as

gwyach, a waterfowl; gwylan, sea-gull; gwydd, goose. Gwysg is related to it,

which means a tendency to a level, as of a fluid or stream. We find the root

in various forms, as Wysg 9 task, uisge, usk, esh, ex, is-ca, &c. Ynys

anciently signified, a quasi-island in the marshes, answering to inch in Scotland,

Inch Keith; and inis or ennis is Ireland, Ennis Killen, Ennis Corthy,

Inniskea, &c The word is applied to some places with no river or water

near them, nor anything suggesting the probability that they had, in remote

times, been islands. Ystrad is a general term for a low or flat valley

through which a river flows. The Latin strata, the Scotch strath, and the

English street are supposed to be of the same origin. The term ystrad was

used sometimes to denote a paved road.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8253) (tudalen 027)

|

27 PLACE-NAMES IN WALES.

Wales. The real and correct name is Cymru, or as the late Mr. T. Stephens

invariably spelt it, Kymru, from cym-bro, the compatriot, the native of the

country, in contradistinction to ail-fro, the foreign invader who came to

dispossess him of his native land. Professor Sylvan Evans derives it from

cyd, the d being changed to m for assimilation with the following b; and bro,

a vale, a country. Some think it is a compound of cyn, first, prior; and

bru, matrix, hence implying Primitive Mother, an expression signifying that

the aboriginal Brythons, to sustain their inalienable claim to the country,

considered themselves as descended from the direct offspring of their native

soil. According to some the name is synonymous with the Cimmerrii and Gomari.

A few derive the name from Camber, the son of Brutus, whilst others insist

upon a remoter origin, and trace it back to Gomer, the eldest son of Japhet.

In the laws of Hywel Dda the name is spelt Cybru, and in G. ap Arthur's

Chronicle the names Kymry and Kymraec are respectively given to the nation

and the language. Mr. Stephens derives Kymry from Homer's Kim meroi and

Germania's Cimbri. These people gave their name to Cumberland, and

subsequently they settled in their present country, and called themselves

Kymry or Cymry, and the country Cymru, Professor Rhys thinks the ties of

union between the Brythons of Upper Britain proved so strong and close that

the word Kymry, which meant merely fellow-countrymen, acquired the force and

charm of a national name, which it still retains among the natives of the

Principality. It is also popularly called Gwalia, of which Wales is a

Saxonized form. Very many favour the German derivation wal, foreign; wallet,

foreigner. The general name given by the Teutonic races to their neighbours

is Walsch, foreigners

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8254) (tudalen 028)

|

28 or strangers. "

The word Dutch is an adjective signifying national, and was the name by which

the old Teutons called themselves in contradistinction to other people, whose

language they were unable to understand. They styled themselves the

(intelligible) people, but called others, as the Romans, and the Kelts in

Britain, iValsch and Welsh.** (Morris* Hist. Gram.). Walsch-land is the

German name of Italy, and Weal-land is the name given by the Saxon Chronicle

to Brittany. Cornwales was the original form of Cornwall 9 which signifies

the country inhabited by the Welsh of the Horn. Some derive the name from

Gal, the ancient Gal, whilst others give the preference to gal, an open,

cultivated Country. " Le Prince de Galles " is the name given to

the Prince of Wales in France. The people of Galatia in the time of St. Paul

possessed some characteristic features of the Celtic race. Mr. Jacob Grim

traces the name back to Galli (Gaules, Fr.), which was taken by the Germans

from the neighbouring Gauls. It is generally supposed that when the Saxons

settled among the Britannic Loegrians (the Kymry of England) they called them

VeaUs, Weala, or Weal has, from which the name Wales probably originated.

Cambria. Some derive it from Camber of fabulous record, but we rather think

it is a distorted Latinized form of Kymry. We shall now proceed to deal with

the names of the ancient territories of Wales, namely, Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed,

and Gwent. Gwynedd, or Venedocia. This territory comprised the counties of

Anglesey, Carnarfon, and Denbigh, or Gwynedd is Gonwy, Venedocia below

Conway, and Gwynedd uch Gonwy, Venedocia above Conway. It was sometimes

applied to all North Wales. The root of the word evidently is Celtic, gwy,

water; nedd, a dingle, a resting place, an abode. The Welsh for a dwelling is

an-nedd. Professor Rhys thinks " the word Veneti is most likely of the

same origin as the Anglo-Saxon wine, a friend, and meant allies; the Irish

fine, a tribe or sept, is most likely related, and so may be the Welsh

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8255) (tudalen 029)

|

2 9 Gwytudd. The Veneti

have left their name to the part of Brittany called by the Bretons Guened,

Vannes, and it is this name probably that laid the foundation for the tales

which trace an army of Kymry from Gwynedd to Guened." (Celtic Britain,

p. 307.) Powys. This included the counties of Meirioneth, Flint, and

Montgomery. The word, according to Dr. Pughe, means a state of rest. Pwyso

means to lean; gorphwyso, to rest. It is said that Ceridwen placed Gwion, the

son of Gwreang, the herald of Llanfair, the fane of the lady, in Caer

Einiawn, the city of the just in Powys, the land of rest. (Davies' Myth., p.

213.) Dyfed, or Demetia. This province embraced the counties of Pembroke,

Carmarthen, and Cardigan; the former constituted the principal part, and is

called Dyfed even to-day by the old inhabitants. In the seventh century Dyfed

consisted only of Pembrokeshire. Some derive the name from Dehtubarth, which

is rather far- fetched. Baxter derives it from defaid, sheep, and bases his

belief on the fact that that part of the country in olden times was noted for

its large number of sheep and goats. We are induced to think the root is

dwfn, deep or low, indicating the geographical position of Dyfed, which is

the lowest part of the Principality. Devon is probably of the same origin.

Demetia is Dyfed Latinized. Gwent. This territory comprised Glamorgan,

Monmouth, Brecon, and Radnor counties. The word denotes an open or fair

region, and was Latinized by the Romans into Venta. Vtnta Silurum is now

Caerwent, in Monmouthshire. ANGLESEY. Anglesey. The Welsh name is Ynys M6n,

the Isle of Mona. M6n is variously derived. Philotechnus derives it from the

Greek monos, alone, left alone, standing alone, from its being separated by

sea from the counties of North Wales. Dr. Owen Pughe seems to endorse the

above: " Man, what is isolated, an isolated one, or that is

separate." The author of Mona

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8256) (tudalen 030)

|

30 Antique derives it

from bdn, a stem, a base, a foundation, from its situation at the extreme

point of the Principality, or, perhaps, from its being called " Mdn, mam

Cymru," Mona, the mother of Wales. We are induced to think that the Isle

of Mona and the Isle of Man derive their names from mon, which means what is

isolated, separate. The English name was bestowed upon it after the battle of

Llanvaes, in which Egbert proved himself victor over Merddyn. In 818 or 819

the Saxon king subdued Mona, and called it Anglesey, or the Isle of the

Angles, or English. The terminal syllable, ey, is the Norse for island.

Aberffraw. This seaport village is situate at the mouth of the river Ffvaw.

Aber, estuary; ffraw means agitation, activity, swiftness. Effraw, awake,

vigilant. The Romans called it Gadavia; gada, to fall or run down; via, way,

signifying the swift or running water. English name Swiftmouth. Amlwch

This name has elicited various conjectures. Some think it is a compound of

aml-Uwch, signifying a dusty place. Others derive it thus: am, round, about;

llwch, a lake, an inlet of water, signifying- a circular inlet of water.

Llwch is cognate with the Scotch loch. Many places in Wales take their names

from this word, as Penllwch, Talyllychau, Llanlhvch, and, perhaps, Amlwch. In

an ancient book, " The Record of Carnarvon," supposed to be written

about 1 451, the name is spelt Amlogh, which induces us to think the right

wording is Aml-och, signifying a place of many groans. Several names in the

district point to the probability that bloody battles were waged here in

ancient times, such as Cadfa, battleplace; Cerryg-y-llefau, stones of

weeping; R.iyd y Galanastra, the ford of massacre; and here Aml-och, 2l place

of many groans. Groaning and weeping are universally the concomitants of

bloodshed and war. English name- Groanston. Beaumaris, Various names are

given to this town Bumaris, Bimaris, Beumarish, Bello-Mariseum, and

Beaumaris. In the Myvyrian list of the parishes of Wales it is spelt

Bywmares. Edmunds derives it from buw, a cow; mor, the sea; and is, low;

signifying the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8257) (tudalen 031)

|

3* low place of cows by

the sea. Some think the name is a compounded form of bis, twice; and maris,

the sea, founding their reason upon the position of the town as lying between

two seas, the Irish Sea and St. George's Channel. Others think the radices

are beau, beautiful, fine, and marie, sea; signifying a place near the

beautiful sea. Many will have the suffix to be marish, marsh, a tract of low

land occasionally covered with water, hence the name signifies the beautiful

marsh. The town was anciently called Forth Wygyr; porth, port; wygyr, perhaps

a contraction of Gwaed-gwyr, men's blood; or it may be a corruption of

Wig-ir; wig gwig, an opening in the wood, a wood; ir, fresh, florid. Pren

ir, a green tree. The new name, Beaumaris, it is said, was given to the town

by Edward I. He built the castle about the year 1285, and changed the name of

the place to Beaumaris, descriptive of its pleasant situation in low ground.

Belan. An abbreviation of Llanbeulan, the church dedicated to Beulan, son

of Paulinus. English name Beulan. Bethel. So called after a Nonconformist

chapel in the village. The sacred edifices of the Established Church are

generally dedicated to eminent Welsh saints; but the Nonconformist

sanctuaries are generally denominated after Scriptural place-names. Bodedern.

Bod, a dwelling-place, an abode; Edern, or Edeyrn, the son of Nudd, the son

of Belt, He was a warrior and a poet, and before the end of his earthly career

he became very devoted to religion, and built a church in this place, which

was dedicated to him, hence the name. English name Kingham. Bodewryd.

This place is situated about four miles west of Amlwch. Bod, a dwelling;

ewryd, a contraction, perhaps, of ewiar, smooth, clear, and rhyd, a ford; the

name, therefore, signifies a mansion at the clear ford. English name

Clearford. Bodffordd. Bod, a dwelling; ffordd, a way, a road; the name,

therefore, signifies a residence by the way or road. English name Wayham.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8258) (tudalen 032)

|

32 Bodwrog. Bod, a

dwelling; Twrog, supposed to be the son of Ithcl Wael, of Brittany, to whom

the church is dedicated. The name signifies a fortified dwelling. English

name Towerham. Brynsiencyn. Bryn, a hill; Siencyn, a Welshified form of

Jenkin, which means little and pretty John. English name Jenkin 's Hill.

Capel Gwyn. Capel, chapel; Gwyn, a contracted form, probably, of Gwyngenau,

the son of Pawl, the elder; or, perhaps, gwyn here has an ecclesiastical

meaning, signifying blessed. " Gwyn ei fyd y gwr," blessed is the

man. English name Blisschapel. Capel Meugan. Capel, chapel; Meugan, son of

Gwyndaf Hen, the son of Emyr Llydaw. Meugan means «* my song." English

name Praise-chapel. Ceirchiog. This name means "abounding with oats.

,, The soil of the district is remarkable for yielding large crops of oats.

English name Oatham. Cemaes. This name is very common in Wales. It is a

compound word, made up of cefn, back, ridge; and mats, a field, signifying a

high field. Some think the name denotes ridged or arable land, from the

fertility of the soil in the district. Others think it is a compounded form

of camp, a feat, a game; and maes, a field. The Welsh had 24 games, or

qualifications, that may be called their course of education. We rather think

the word must be understood here in a martial sense, signifying a field on a

high place, forming a vantage-ground for military operations. The name

indicates signs of the defensive conflict of the Kymry from the time of

Cadwaladr down to the fall of Llewellyn, with whom the independence of

Cambria terminated. English name Highfield. Cerryg Cbinwen. Cerryg,

stones; Ceinwen, the daughter of Brychan Brycheiniog, to whom the church is

dedicated. English name Fairstone. Cerryg y Gwyddyl. Cerryg, stones;

Gwyddyl, Irishmen. Caswallon Law-Hir (Long Hand), about the year 500, fought

valiantly against the Irish invaders in North Wales. Having achieved such a

*ndGfc Gwis DY.. L^U SB" -

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd 8259) (tudalen 033)

|

33

noble victory at a

certain place in Mona, he built a church thereon, and called it Llany

Gwyddyl, but now it is known by the name of Cerrygy GwyddyL English name

Woodstone. Clegyrog. The root, probably, is clegr, which means a rock, a

cliff.

Clegyrog, rocky, rugged;

the name is quite descriptive of this craggy district. English name

Kockton.

Coedana. Coed, wood;

Ana- Anne, supposed to be a Welsh lady to whom the parish church is