|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6001) (tudalen i)

|

Clarendon

Press Series

THE PHILOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH TONGUE

BY JOHN EARLE, M.A. Professor of

Anglo-Saxon in the University of Oxford

THIRD EDITION. NEWLY REVISED AND IMPROVED

Oxford AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

MDCCCLXXIX

(All Rights Reserved)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6002) (tudalen ii)

|

MACMILLAN

AND CO.

PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6003) (tudalen iii)

|

PREFACE

TO THE FIRST EDITION.

Philology may be described as a science of language based upon the comparison of languages. It is the

aim of Philology to order the study of

language upon principles indicated by language itself, so that each part and

function shall have its true and

natural place assigned to it, according to the order, relation, and proportion dictated by the nature of

language. What the nature of language

is, can be ascertained only by a wide comparison of languages taken at

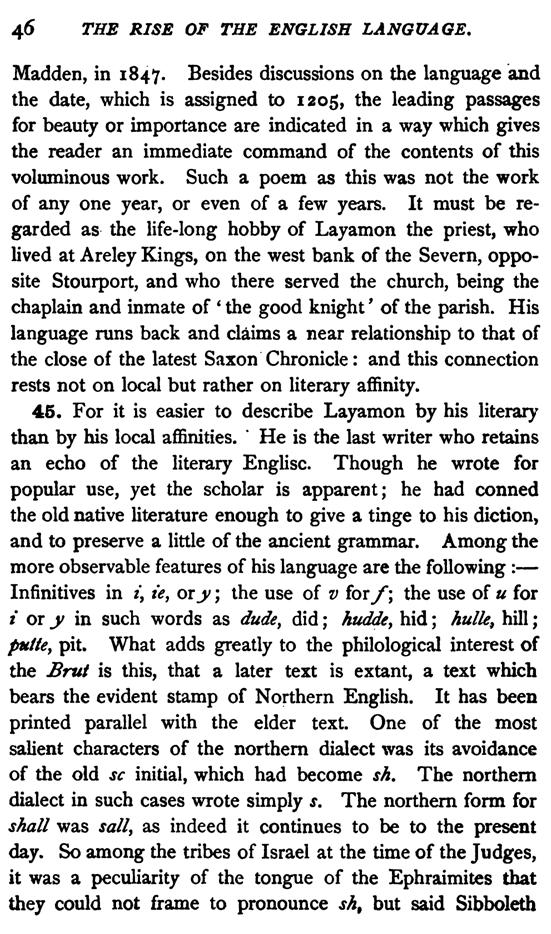

various stages of development. Such a

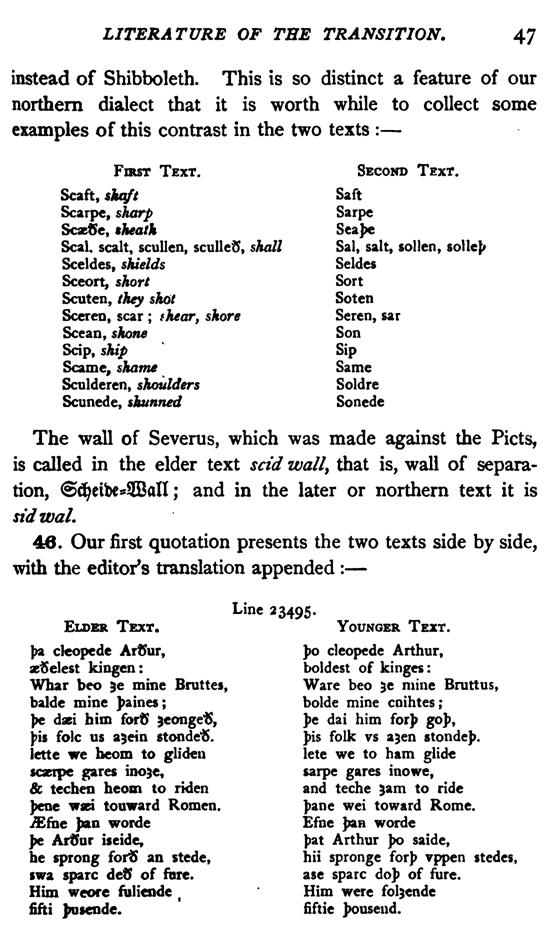

work is to be performed, not by any one man, but by the co-operation of many : and many have now

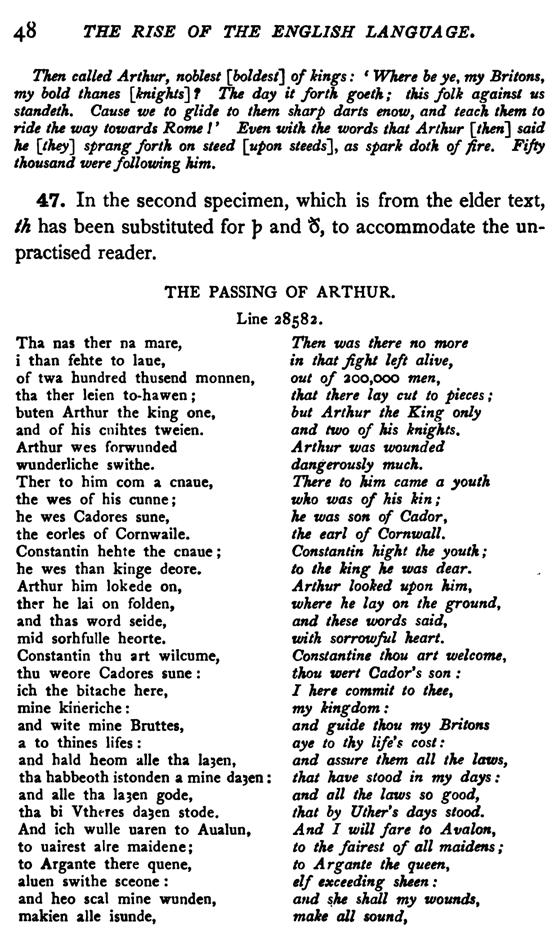

been co-operating for three quarters

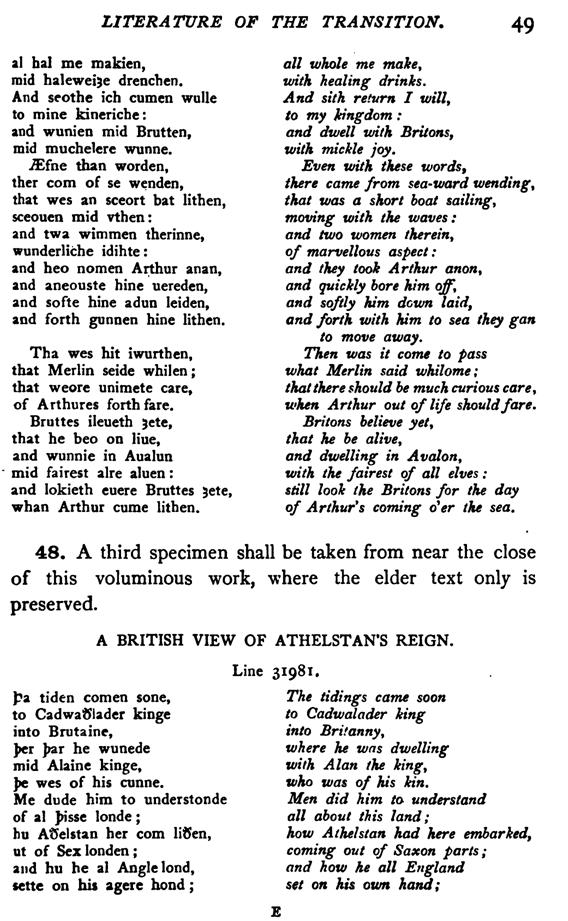

of a century past, and sending in from every

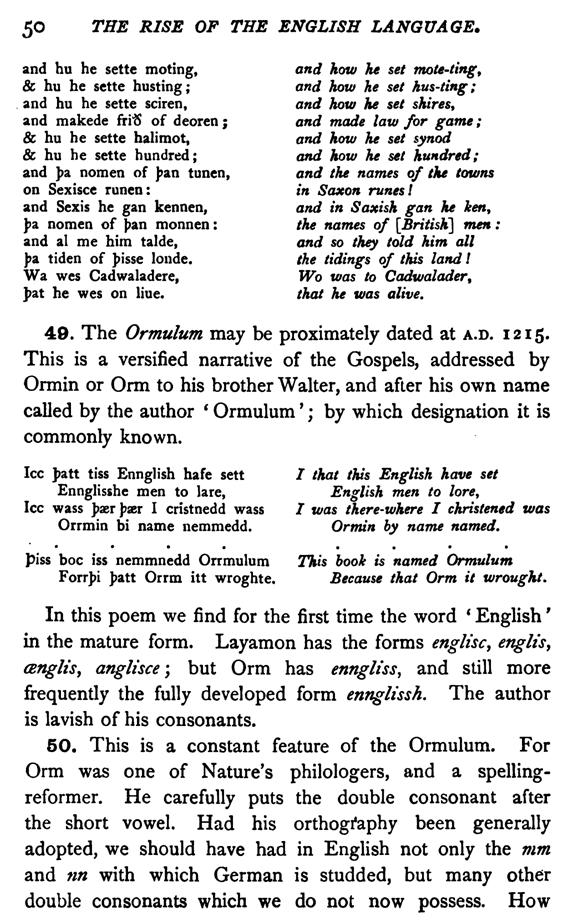

land their contributions towards it.

In this newly gotten knowledge of human language there is matter for educational use. The relations

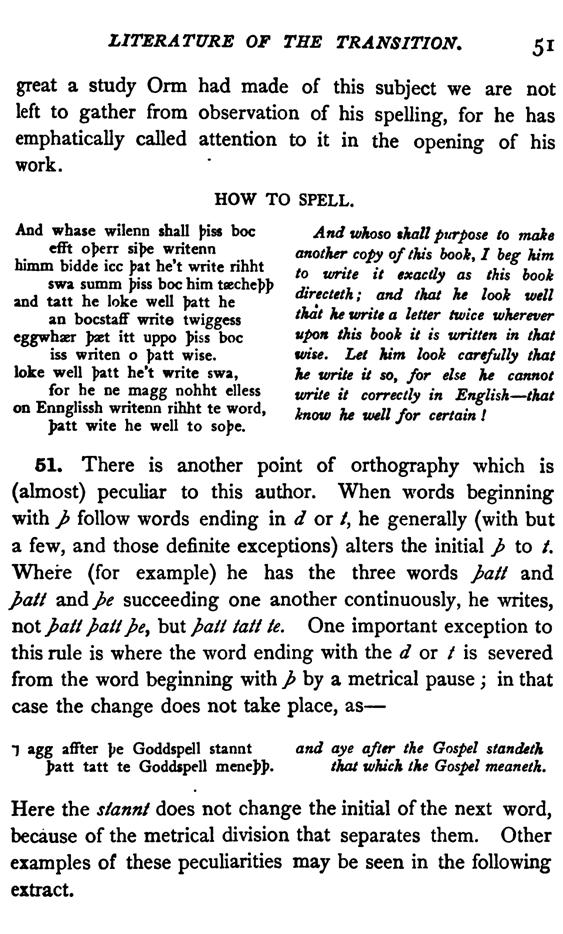

of language to culture are so intimate

tliat what betters our knowledge of the one

should improve the process of the other. It is an open question, in what way the lessons of language may

best be converted to the purpose of

education, but there is one fault which might at least be somewhat mended : our knowledge of

language has been too broken and

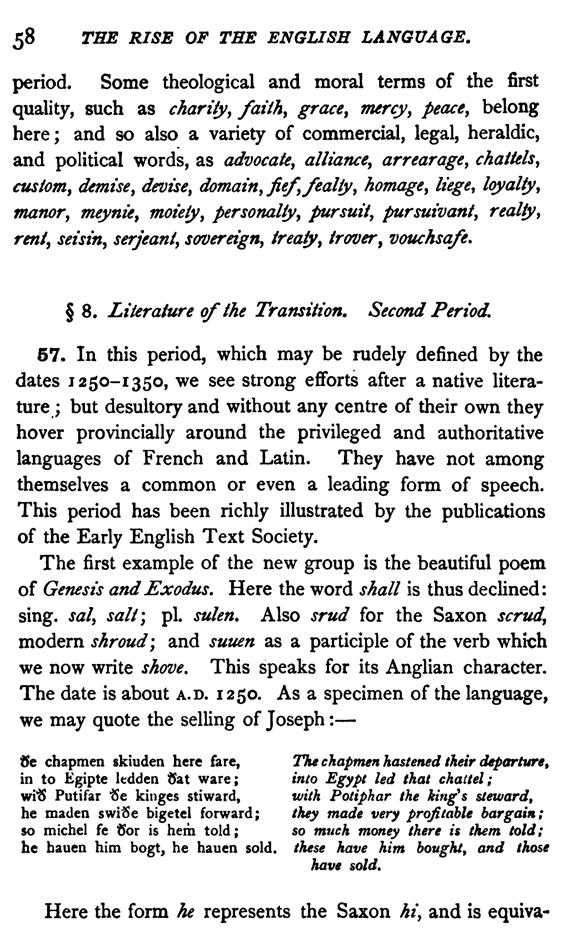

divided : we have most of us known one language best vernacularly, and another best

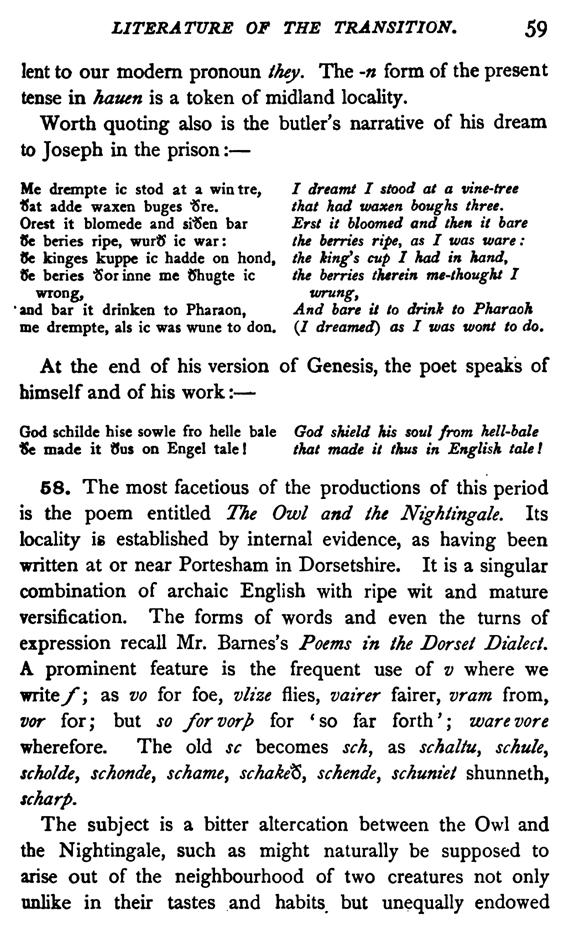

grammatically. Something would be

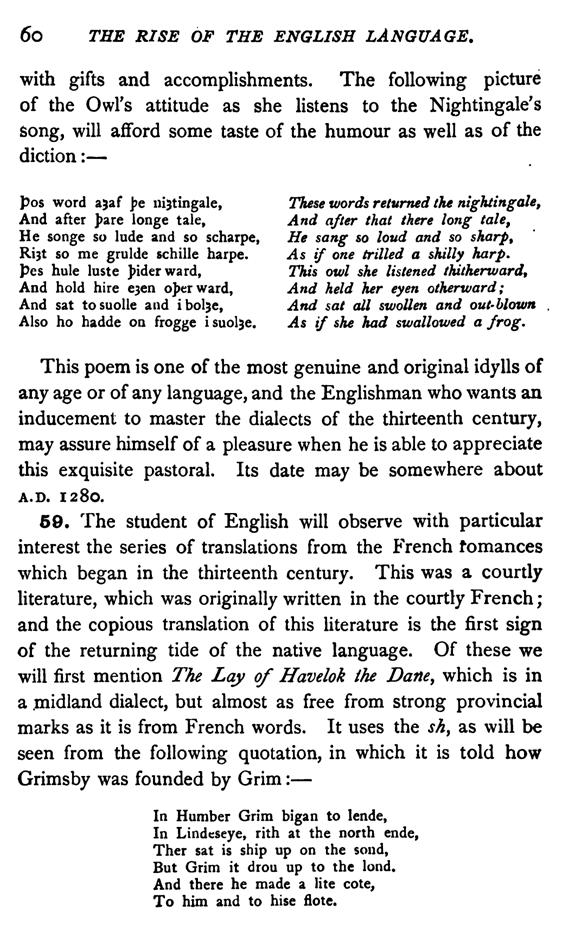

gained if our cultivation of language could be rather more centred upon the mother tongue, so

that our vernacular and our

philological acquirements might more effectually support one another. The lessons of philology would

be taught more thoroughly, as well as

more conveniently, if the materials for the

instruction were supplied by the mother tongue. The effect of philological study is to quicken the

perception of analogy between

languages; and this advantage would be more immediate in its

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6004) (tudalen iv)

|

IV

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

returns if our philology were more based on the mother tongue. Nothing would put the learner so readily or

so implicitly in possession of all the

essence of philological gains ; nothing would

be of such good practical avail whenever the knowledge of our language was needed to bear upon the

acquisition of another. Were the

English language studied philologically, the faculty of acquiring other languages would be more

generally an English faculty. .

There are two chief ways of entering upon a scientific study. One is by the way of Principles, and the

other is by the way of Elements. If

the learner approaches Philology by the way of principles, it is necessary that the

principles should be familiarised to him by the aid of examples and

illustrations drawn from various

languages. Each of the methods excels in its own peculiar way ; and the

excellence of this method is, that the subject is presented with the greatest fullness and

totality of effect as a mountain is

most imposing to the view on its most precipitous side. But it has this great drawback,

that the learner can ill judge of the

examples ; he must take them on authority ; and so far forth as the instruction is based on

facts which are not within the

cognisance of the learner, the teaching is unscientific.

The other method is by the examination of a single language ; and here the course of treatment follows

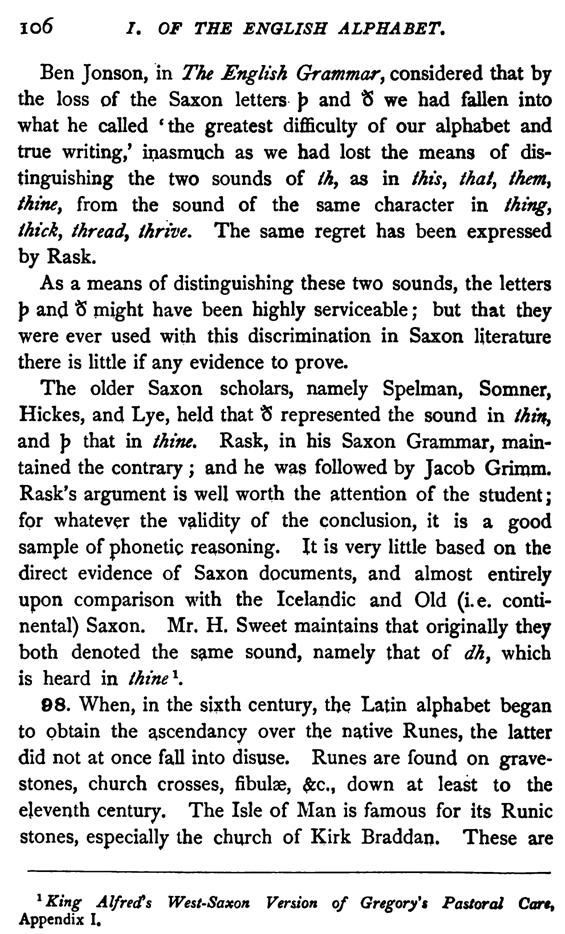

the order of natural growth,

introducing the principles in an occasional and incidental manner, just as they happen to be called

for in the course of the

investigation. If the object-language be the learner's own vernacular, this course will be something

like climbing a mountain by the side where the slope is easiest. "When

this path is chosen, the complete and

compact view of principles as a whole

will be deferred until such time as the learner shall have reached them severally by means of facts which lie

within his own experience. It is upon this, which may be called the

Elementary method, that the present

manual has been constructed ; the aim

of which has been to find a path through most familiar ground up to philological principles.

It was assumed at starting that the English language would furnish examples of all that is most

typical in human speech, and

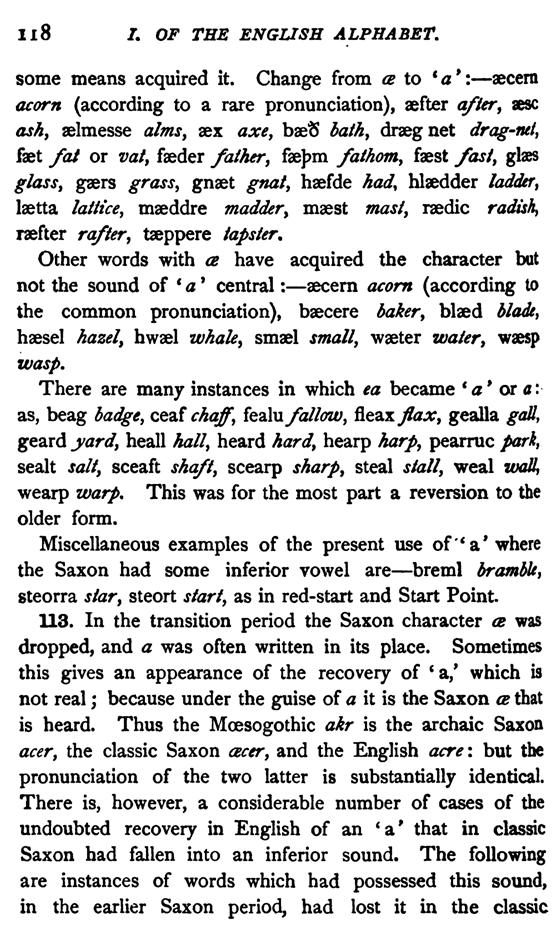

|

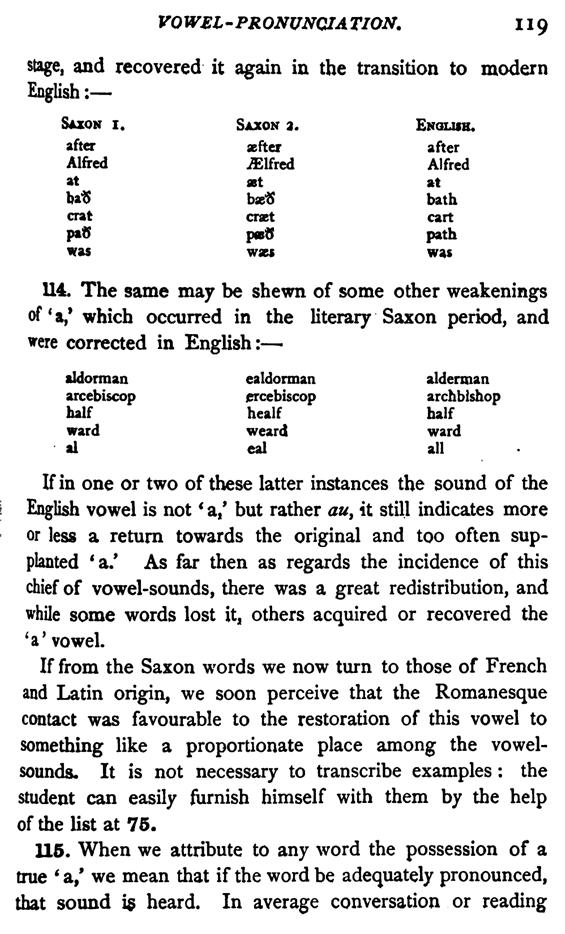

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

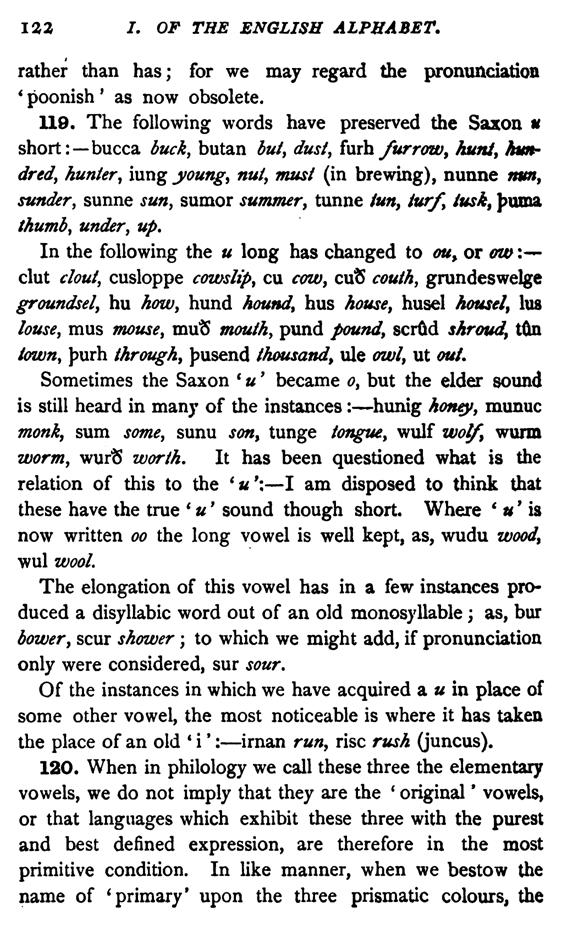

|

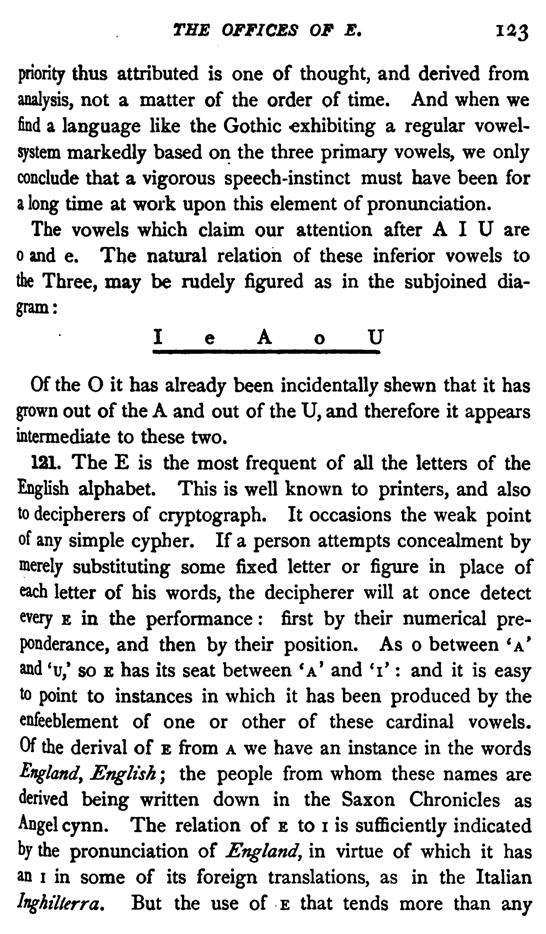

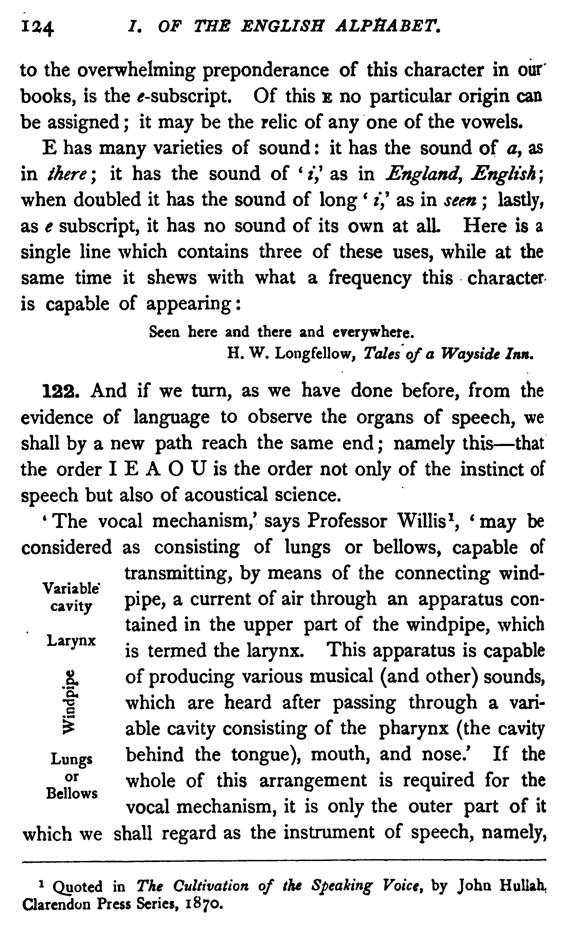

|

|

(delwedd E6005) (tudalen v)

|

PREFACE

TO THE SECOND AND THIRD EDITIONS. V

it has been the reward of the labourer in this instance that his anticipation of the fecundity of his

material has been most abundantly and

even unexpectedly verified.

The excellent verbal Index is the work of H. N. Harvey, Esq., of the Ordnance Survey Office, Southampton

; and while it is the most valuable

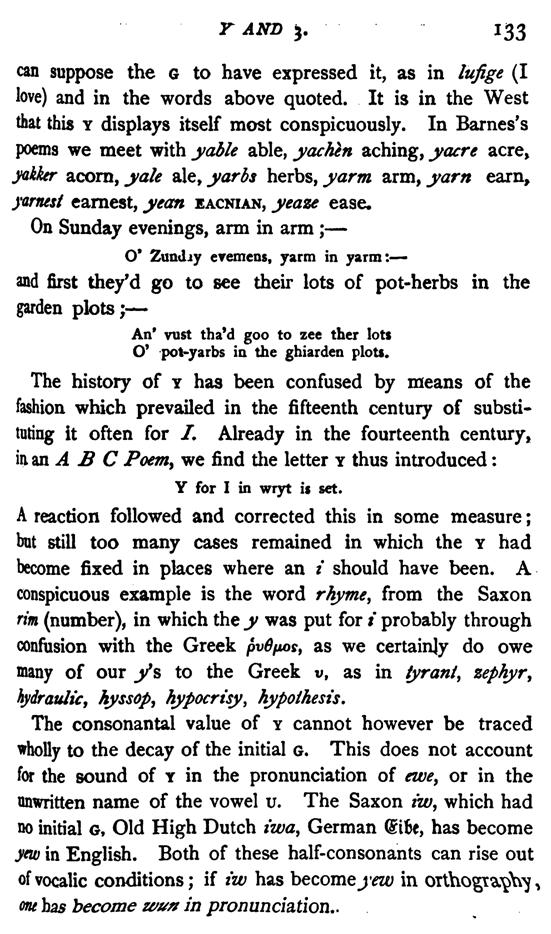

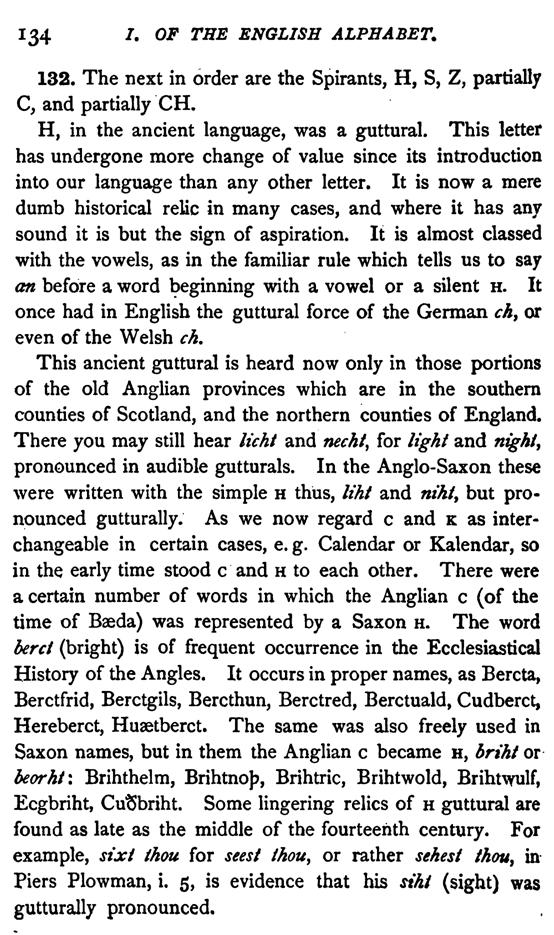

addition that this handbook could have received, it is by me still more highly esteemed as a

new token of an old friendship.

Whatley Rectory, July, 1871.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

In this Edition I have freely altered wherever I thought I could improve; but this has not occasioned

a single change in matter of

principle, or in the general plan of arrangement. Notwithstanding many

variations of detail, this Edition is essentially one with the First.

The most considerable additions are in the Phonology of the First and Second Chapters, and in the

Particle-Composition of the Eleventh.

The division into paragraphs has made it necessary to reconstruct the Index

anew, and for this work I am again indebted to the same unwearied friend as before.

SwANSwicK, April 21, 1873.

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION.

Any one who has considered the extensive range and the manifold complexities of the English

language, will not marvel if a

describer of it has still found room for improvement, even in a Third Edition. Apt illustrations

cannot always be caught when required,

they must be waited for. Some such have been

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6006) (tudalen vi)

|

VI PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION.

secured in the interval since the Second Edition, and have taken their place in the text. Also many little

points of arrangement and proportion

have received their due attention. Diminutives are treated more fully. Some remarks upon

Adjectives of Vogue, incidentally

sprinkled, have been collected into one place. But these improvements never alter the plan,

and often they do but fill it out. Not

only is the original framework left intact;

it is lifted into higher relief. Such is plainly the eiFect where the number of verbal examples has been increased.

For the consequent expansion of the

Word-Index, I have again to record my

hearty thanks as twice before.

Some petty changes are for economy of space and compactness of view. When an

English word is mated with a remoter

word unlabelled, that word is generdly of the language which gives note to the Section. Thus, in 'main

maegen,* p. 299, the heading indicates

that the unlabelled maegen is Saxon. If this is not perfectly carried out, the exceptions

are such as to cause no uncertainty. '

The oft-repeated names, Chaucer, Shakspeare,

Spenser, Milton, Tennyson, are frequently indicated by abbreviations

which speak for themselves.

In the Verbal Index some further progress has been made in distinguishing classes of words by

diversities of type. The Index of

Subjects has been considerably enlarged, and I hope it will be found serviceable for occasions of

reference. But at the same time I wish

to say that the book was cast as a whole, and that as a whole it is commended to the student's

attention ; because an adequate

notion of the English language is not to be acquired from this or that interesting particular,

nor from any number of such ; but only

from a resolute endeavour to apprehend the language in its living unity, as

well in the rich and almost; endless

variety of its parts and functions, as also in the admirable freedom

and simplicity of its action.

Maltby, July 2, 1879.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6007) (tudalen vii)

|

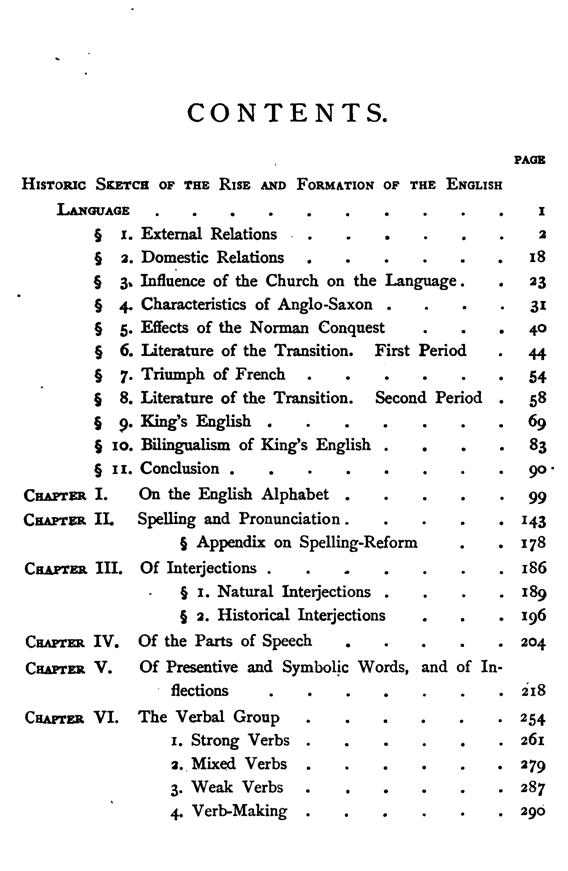

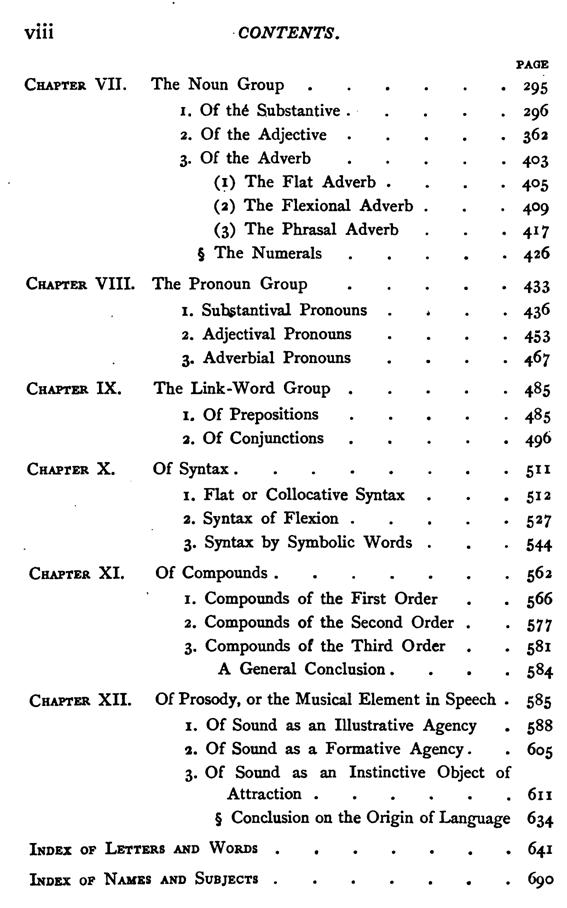

CONTENTS.

PAGE

Historic Sketch of the Rise and Form/^tion op the English

Language i

§ I. External Relations 2

§ 2. Domestic Relations 18

§ 3k Influence of the Church on the Language . . 23

§ 4. Characteristics of Anglo-Saxon .... 31

§ 5. Effects of the Norman Conquest ... 40

§ 6. Literature of the Transition. First Period . 44

§ 7. Triumph of French 54

§ 8. Literature of the Transition. Second Period . 58

§ p. King's English 69

§ 10. Bilingualism of Eling's English .... 83

§ II. Conclusion 90

Chapter I. On the English Alphabet 99

Chapter IL Spelling and Pronunciation 143

§ Appendix on Spelling-Reform . .178

Chapter IIL Of Interjections 186

§ I. Natural Interjections . . . .189

§ 2. Historical Interjections . . .196

Chapter IV. Of the Parts of Speech 204

Chapter V. Of Presentive and Symbolic Words, and of Inflections 218

Chapter VI. The Verbal Group 254

1. Strong Verbs 261

2. Mixed Verbs 279

3. Weak Verbs 287

4. Verb-Making 290

viii

CONTENTS.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6008) (tudalen viii)

|

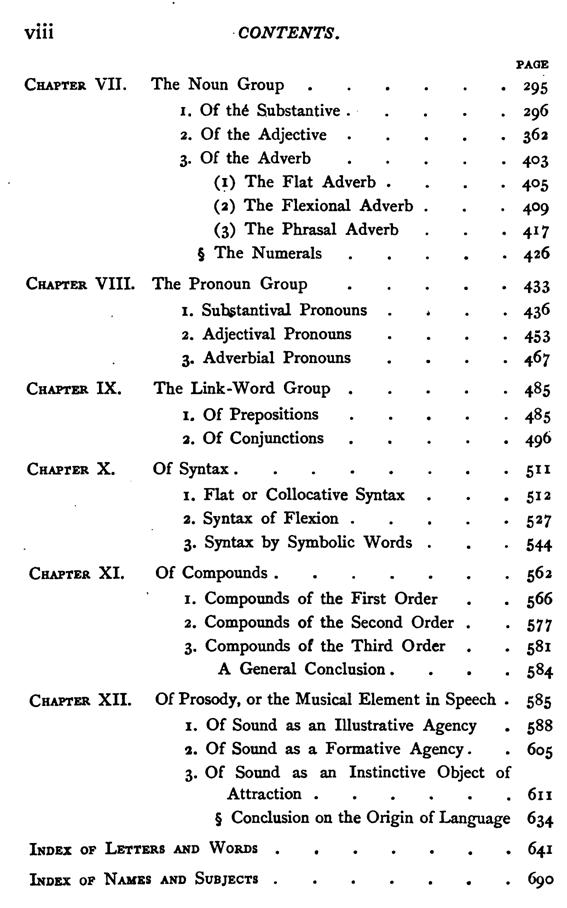

PAGE

Chapter VII.

The Noun Group

295

I. Of th6 Substantive . .

. 296

2. Of the Adjective

. 362

3. Of the Adverb

403

(I) The Flat Adverb .

405

(2) The Flexional Adverb .

409

(3) The Phrasal Adverb .

. 417

§ The Numerals

. 426

Chapter VIII.

The Pronoun Group

433

I. Substantival Pronouns .

. 436

2. Adjectival Pronouns

453

3. Adverbial Pronouns

. 467

Chapter IX.

The Link -Word Group .

. 485

I. Of Prepositions

. . 485

2. Of Conjunctions

. 496

Chapter X.

Of Syntax

. 511

I. Flat or CoUocative Sjmtax

. 512

2. Syntax of Flexion .

527

3. Syntax by S)rmbolic Words

544

Chapter XI.

Of Compounds ....

. 562

I. Compounds of the First Order

. . 566

2. Compounds of the Second Order

577

3. Compounds of the Third Order

. 581

A General Conclusion .

. . 584

Chapter XII.

Of Prosody, or the Musical Element in

Spi

sech . 585

I. Of Sound as an Illustrative Agenc

y . 588

2. Of Sound as a Formative Agency

. 605

3. Of Sound as an Instinctive Obj<

;ct of

Attraction ....

. 611

§ Conclusion on the Origin of I^n

guage 634

Index of Letters and Words

. 641

Index op Names and Subjects ....

. 690

li

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6009) (tudalen 001)

|

HISTORIC

SKETCH

OF THE RISE AND FORMATION

OF THE

ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

\ 1. The Philology of a language includes all that is meant by its Grammar, and yet it is at the same

time a distinct study. This difference

hinges upon the point of view from

which the language is contemplated. In grammar the view is confined to the particular language,

while in philology the language is

considered in regard to its external relations. In grammar we seek rules for the regulation

of domestic usage : in philology we

seek principles to explain the habits

of speech. Further, the rules of grammar are justified by reference to the logical sense : the

laws of philology have to be

established by external comparison and induction. Thus grammar is a local and internal study

of language : philology is outward and

(in its tendency) universal.

This outward look of philology takes two principal directions. In the first

place it will lead us to enquire into

the earlier habits of the particular language, that we may be able to trace by what process of

development it

B

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6010) (tudalen 002)

|

2, THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

reached its present condition. This is the historical aspect of philology. In the second place, it will

lead us to seek further historical

knowledge with a view to the comparison

of our language with other languages, in order that we may be able to discover principles of

development and structure, and base

the framework of our particular language as far as possible upon lines which are common to

many languages, with the ultimate aim

of seeking that which is universal and

essential to all.

The position which our language assumes in the comparative scheme, is

remarkable and peculiar. Starting as

one of the purest and least mixed of languages, it has come to be the most composite in the world. And

the particular greatness of the

English language is inseparable from this

characteristic. Languages there may be which surpass ours in this or that quality, but there is none

which unites in itself so many great

qualities, none in which functions so

diverse and various harmonidusly cooperate, none which displays so full a compass of the powers

and faculties of human speech.

The details of this statement will occupy the twelve chapters below: but first I will

endeavour to indicate the historical

events which prepared for the English language its remarkable career; and this calls for

an Introductory discourse.

§ 1. External Relations,

2. The English is one of the languages of the great IndoEuropean (or Aryan)

family, the members of which have been

traced across the double continent of Asia and Europe through the Sanskrit, Persian, Greek,

Latin, Slavonic, Gothic, and Keltic

languages. In order to illustrate the right of our

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6011) (tudalen 003)

|

MXTERNAL

RELATIONS. 3

English language to a place in this series, it will suflSce to exhibit a few proofs of definite

relationship between our language on

the one hand, and the classical languages of

Greece and Italy on the other. The readiest illustration of this is to be found in the Transition of

Consonants. When the same words appear

under altered forms in diflferent members

of the same family of languages, the diversity of form is found to have a regular method and analogy.

Such an analogy has been established

between the varying consonants which

hold analogous positions in cognate languages, and their variation has been reduced to rule by

the German philologer Jacob Grimm. He

has founded the law of Consonantal Transition, or consonantal equivalents.

A few easy examples will put the reader in possession of the nature of this law. When a Welshman

speaks English in Shakspeare he often

substitutes p for b, as Fluellen in

Henry K, v. i : * Pragging knave, Pistoll, which you and yoiu-self and all the world know to be no

petter than a fellow, looke you now,

of no merits : hee is come to me, and

prings me pread and sault yesterday, looke you, and bid me eate my leeke,' &c. The Welsh parson.

Sir Hugh Evans, in Merry Wives, puts t

for d : * It were a goot motion ' * The

tevil and his tarn ' and * worts * for words, as : ^

* Evans. Pauca verba ; (Sir /okn) good worts.

F^TAFFE. Good worts? good cabidge.'

Likewise f for v : * It is that ferry person for all the orld' ; and 'fidelicet* for 'videlicet' *I most

fehemently desire you,' &c.

3. This familiar illustration has lost none of its force since the time of Shakspeare. A recent traveller

in North Wales saw a railway truck at

Conway on which some Welsh porter had

chalked ' Chester goots.' This variation, at which we

B 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6012) (tudalen 004)

|

4 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

smile as a provincial peculiarity, ofifers the best clue to a universal law of phonetic transition. It is

not confined to one country or to one

family of languages.

The Semitic family, which is the great contrast to the Indo-European, follows the same path in the

phonetic variations of its dialects.

Between the Hebrew and Chaldee there is a well-marked interchange of z and d; while a third

dialect, the Phoenician, seems to have put a t for z (ts). The Hebrew pronoun for this is zeh; but in Chaldee it

becomes DAA and DEN and di : the

Hebrew word for male is zakar ; but in

Chaldee it appears as dekar: the Hebrew verb to sacrifice is zavach ; but in Chaldee it is

devach : the Hebrew verb for being

timid is zachal ; but in Chaldee it is

DECHAL. If we compare Hebrew with the third dialect we get T for z. The Hebrew word for rock is

zoor or tsoor, after which a famous

Phoenician city seated on a rock was

called ZoR, as it is always called in the Old Testament ; but this word sounded in Greek ears from

Phoenician mouths so as to cause them

to write it Tv^oy, Tyrus^ whence we have

the name Tyre. It is to this sort of play upon the gamut or scale of consonants, a play which is

kept up between kindred dialects, that

Grimm, when he had reduced it to a

law, gave the name of Lauiverschiebungy or Consonantal Transition, reciprocity of consonants.

As, on the one hand, we find this reciprocity where we find cognate dialects ; so, on the

other, if we can establish the fact that there is or has been such a

consonantal reciprocity between two

languages, we have obtained the

strongest proof of their relationship. There are traces of this kind between the English on the one

hand and the Classical languages on

the other.

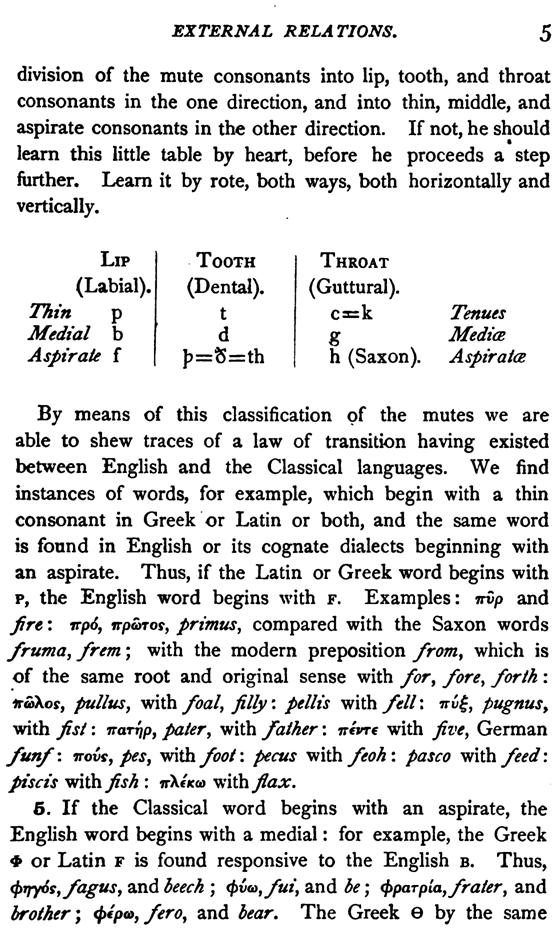

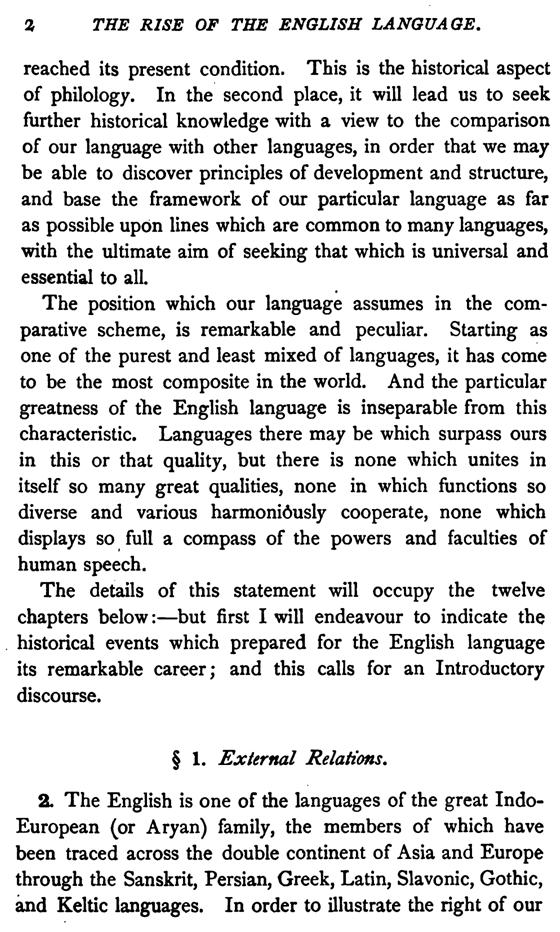

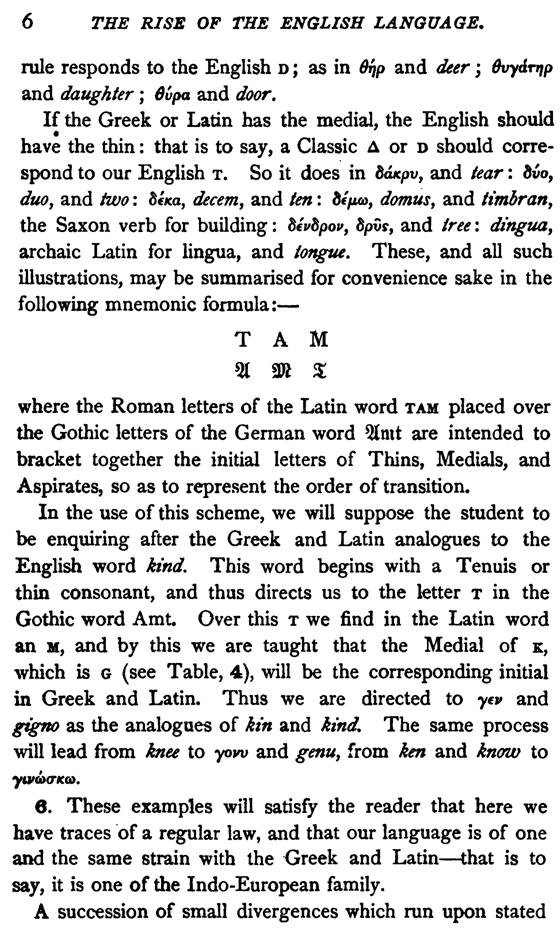

4. We suppose the reader is familiar with the twofold

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6013) (tudalen 005)

|

EXTERNAL

RELATIONS. 5

division of the mute consonants into lip, tooth, and throat consonants in the one direction, and into

thin, middle, and aspirate consonants

in the other direction. If not, he should

learn this little table by heart, before he proceeds a step further. Learn it by rote, both ways, both

horizontally and vertically.

Lip

Tooth

Throat

(Labial).

Tkin p Medial b Aspirate f

(Dental).

t

d

]?=8=th

(Guttural).

c=k

g

h (Saxon).

Tenues

MedicB AspiratcB

By means of this classification of the mutes we are

able to shew traces of a law of transition having existed

between English and the Classical languages. We find

instances of words, for example, which begin with a thin

consonant in Greek or Latin or both, and the same word

is found in English or its cognate dialects beginning with

an aspirate. Thus, if the Latin or Greek word begins with

p, the English word begins with f. Examples: injp and

fre : irp6, irpSiros, primus, compared with the Saxon words

fruma, /rem ; with the modern preposition /romf which is

of the same root and original sense with /or, /ore, forth :

fr^Xof, pullus, with foal, filly : pellis with /ell : irv^, pugnuSy

with fist : Trarrip, pater, with /ather : Ttkim with five, German

/un/\ irovi, pes, vf\\h/oot\ pecus withy^^^: pasco vf\\h/eed:

piscis vn\}ci.fish : ttXcico) with^aji;.

6. If the Classical word begins with an aspirate, the English word begins with a medial : for

example, the Greek * or Latin f is

found responsive to the English b. Thus,

4>rr/^s,/agus, and beech ; <^va),y«/, and be ; <l>paTpia,

/rater, and brother; <l>pa,

/ero, and bear. The Greek e by the same

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6014) (tudalen 06)

|

6 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

rule responds to the English d ; as in ^p and deer ; Ovydrrip and daughter ; ^upo and door.

If the Greek or Latin has the medial, the English should have the thin : that is to say, a Classic A

or d should correspond to our English t. So it does in daicpu, and tear :

dvo, duo, and two : hkKa, decern, and

ten : dcfia>, domus, and timhran,

the Saxon verb for building : dhdpou, dpvs, and /r^f^ : dingua, archaic Latin for lingua, and torque.

These, and all such illustrations, may

be summarised for convenience sake in the

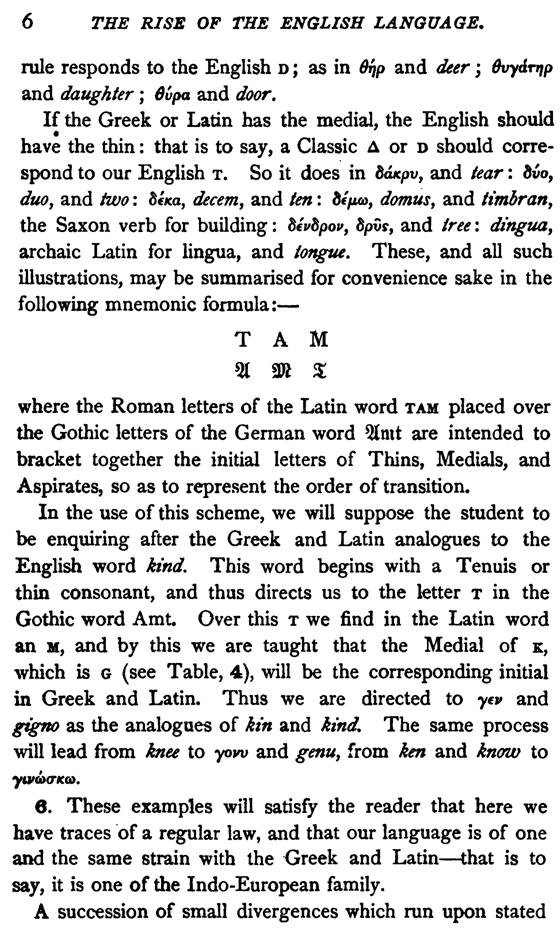

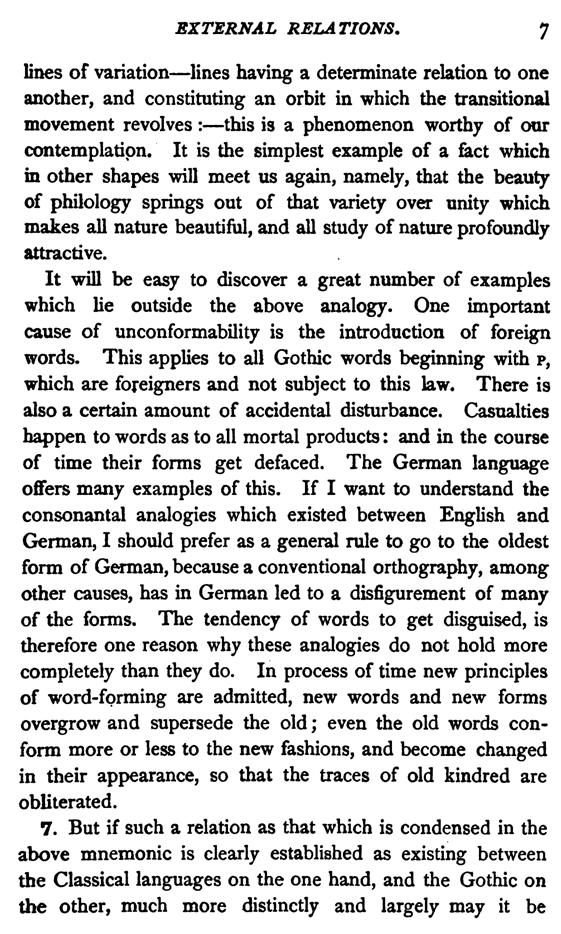

following mnemonic formula:

T A M

% m %

where the Roman letters of the Latin word tam placed over the Gothic letters of the German word ?tmt

are intended to bracket together the

initial letters of Thins, Medials, and

Aspirates, so as to represent the order of transition.

In the use of this scheme, we will suppose the student to be enquiring after the Greek and Latin

analogues to the English word kind.

This word begins with a Tenuis or thin

consonant, and thus directs us to the letter x in the Gothic word Amt. Over this t we find in the

Latin word an M, and by this we are

taught that the Medial of k, which is

G (see Table, 4), will be the corresponding initial in Greek and Latin. Thus we are directed to

y^v and gigno as the analogues of kin

and kind. The same process will lead

from knee to yow and genu, from ken and know to

6. These examples will satisfy the reader that here we have traces of a regular law, and that our

language is of one and the same strain

with the Greek and Latin that is to

say, it is one of the Indo-European family.

A succession of small divergences which run upon stated

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6015) (tudalen 007)

|

EXTERNAL

RELATIONS. 7

lines of variation lines having a determinate relation to one another, and constituting an orbit in which

the transitional movement revolves :

this is a phenomenon worthy of our

contemplation. It is the simplest example of a &ct which in other shapes will meet us again, namely,

that the beauty of philology springs

out of that variety over unity which

makes all nature beautiful, and all study of nature profoundly attractive.

It will be easy to discover a great number of examples which He outside the above analogy. One

important cause of unconformability is

the introduction of foreign words.

This applies to all Gothic words beginning with p, which are foreigners and not subject to

this law. There is also a certain

amount of accidental disturbance. Casualties

happen to words as to all mortal products : and in the course of time their forms get defaced. The German

language offers many examples of this.

If I want to understand the

consonantal analogies which existed between English and German, I should prefer as a general rule

to go to the oldest form of Gwinan,

because a conventional orthography, among

other causes, has in German led to a disfigurement of many of the forms. The tendency of words to get

disguised, is therefore one reason why

these analogies do not hold more

completely than they do. In process of time new principles of word-forming are admitted, new words and

new forms overgrow and supersede the

old ; even the old words conform more or less to the new fashions, and become

changed in their appearance, so that

the traces of old kindred are

obliterated.

7. But if such a relation as that which is condensed in the above mnemonic is clearly established as

existing between the Classical

languages on the one hand, and the Gothic on

the other, much more distinctly and largely may it be

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6016) (tudalen 008)

|

8 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE,

shewn that a like relation exists internally between the two main subdivisions of the Gothic family.

These two parts arethe High Dutch and

the Low Dutch. The Modern or New High

Dutch is what we now call * German/ the great

literary language of Central Europe, inaugurated by Luther in his translation of the Bible. Behind

this great modern speech we have two

receding stages of its earlier forms,

the Middle High Dutch or the language of the Epic of the Nibelungen, and the Old High Dutch or

the language of the Scripture

paraphrasts Otfrid and Notker. The

Alt-Hoch-Deutsch goes back to the tenth century; the Mittel-Hoch-Deutsch goes back to the

thirteenth; and the Neu-Hoch-Deutsch

dates from the Reformation of the

sixteenth century. This is the High Dutch division of the Gothic languages.

Round about these, in a broken curve, are found the representatives of the Low Dutch family.

Their earliest literary traces go back

to the fourth century, and appear in

the villages of Dacia, in lands which slope to the Danube ; where the country is by foreigners called

Wallachia. It is from this region that

we have the Moesogothic Gospels and

other relics of the planting of Christianity. But the greatest body of the Low Dutch is to

the north and west of Germany. Along

the shores of the Baltic, and far

inland, where High Dutch is established in the educated ranks, the mass of

the folk speak Low Dutch, which

locally passes by the name of Platt-Deutsch. The kingdom of the Netherlands, where it is a

truly national speech, the speech of

all ranks of the community the

kingdom of Belgium, where, under the name of Flemish, it is striving for recognition, and has

gained a place in literature through

the pen of Hendrik Conscience the

old district of the Hanseatic cities, the Lower Elbe,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6017) (tudalen 009)

|

EXTERNAL

RELATIONS. 9

Hamburgh, Ltibeck, Bremen, all this is Nieder-Deutsch, Low Dutch.

8. To this family belongs the English language in respect of that which is the oldest and most

material part of it. It has received

so many additions from other sources, and

has worked them up with so much individuality of effect, as to have in fact produced a new language,

and a language which, from external

circumstances, seems likely to become

the parent of a new strain of languages. But all the outgrowth and

exuberance of the English language clusters

round a Low Dutch centre.

It would be a departure from the general way of philologers to include under the

term of Low Dutch the languages of

Scandinavia. The latter have very strong individualising features of their own, such as the

post-positive article, and a form for

the passive verb. The post-positive article is highly curious. In modern Danish or Swedish

the indefinite article a or an is represented by en for masculine and feminine, and ef for neuter. Thus en skov

signifies a wood (shaw) and ei irce

signifies a tree. But if you want to say

the wood, the tree, you suffix these syllables to the nouns, and then they have the effect of the

definite article ; skoven, the wood ;

trceet, the tree ; Juletrceet, the Christmas tree.

9. The possession of a form for the passive is hardly less remarkable, when we consider that the

Gothic languages in general make the

passive, as we do in English, by the aid

of the verb to be. Active to love, passive to be loved. But the Scandinavian dialects just add an s to

the active, and that makes it passive.

This j is a relic of an old reflexive

pronoun, so that it is most like the French habit of getting a sort of a passive by prefixing the

reflexive pronoun se. Thus in French

marier is to marry (active), of parents who

marry their children ; but if you have to express to marry

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6018) (tudalen 010)

|

10 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

in the sense of to get married or to be married, you say se marier. Examples of the Danish passive form

:

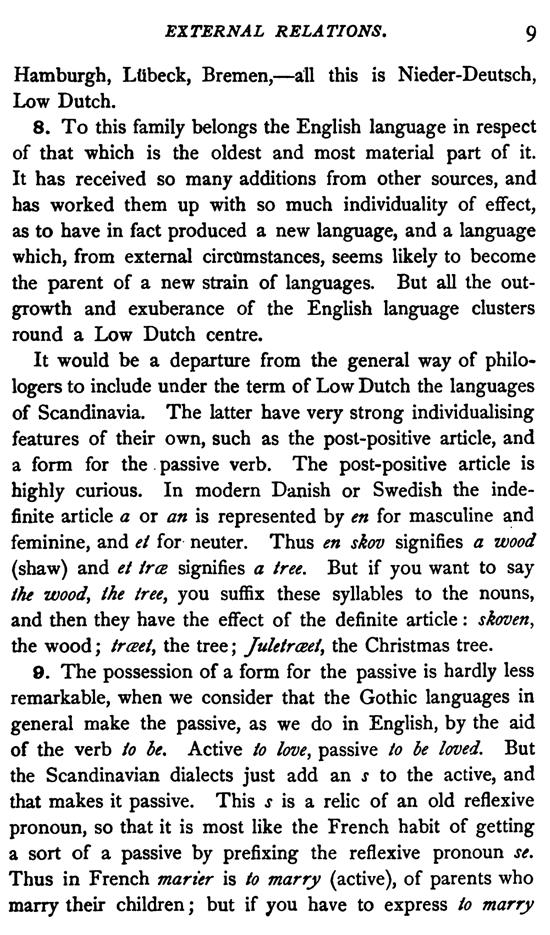

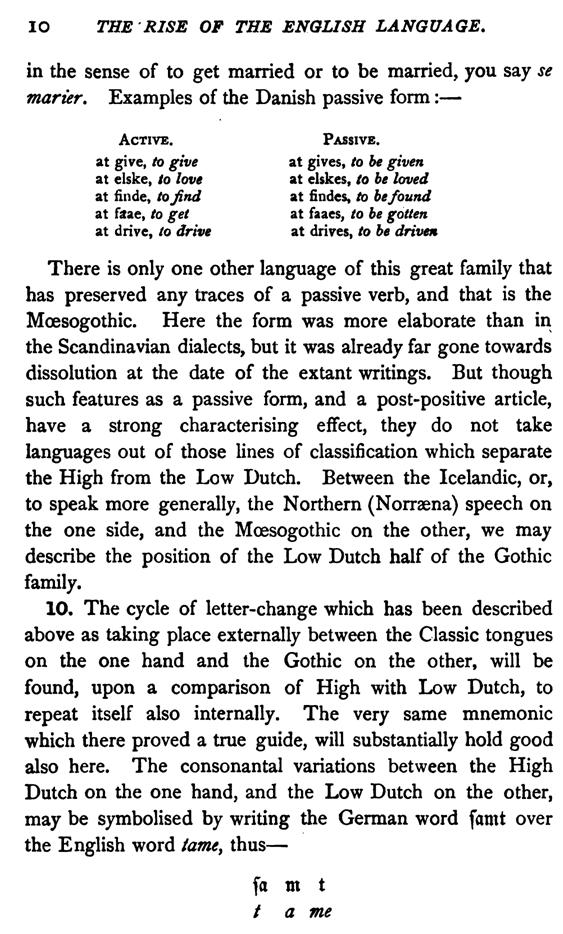

Active. Passive.

at give, to give at gives, to he given

at elske, to love at elskes, to be loved

at finde, to find at findes, A) he found

at fsae, to get at faaes, to he gotten

at drive, to drive at drives, to he driven

There is only one other language of this great family that has preserved any traces of a passive verb,

and that is the Moesogothic. Here the

form was more elaborate than in the

Scandinavian dialects, but it was already far gone towards dissolution at the date of the extant

writings. But though such features as

a passive form, and a post-positive article,

have a strong characterising effect, they do not take languages out of those lines of

classification which separate the High

from the Low Dutch. Between the Icelandic, or, to speak more generally, the Northern

(Norraena) speech on the one side, and

the Moesogothic on the other, we may

describe the position of the Low Dutch half of the Gothic family.

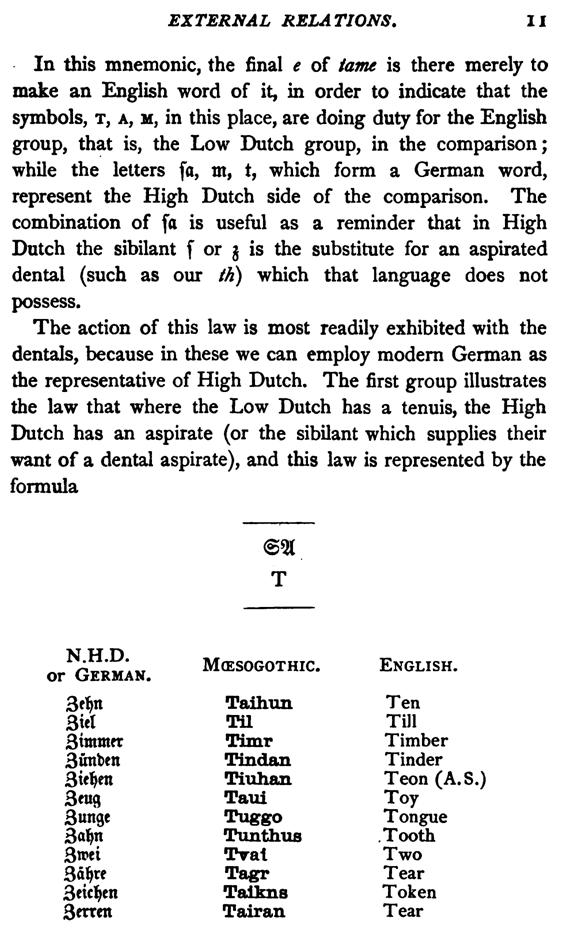

10. The cycle of letter-change which has been described above as taking place externally between

the Classic tongues on the one hand

and the Gothic on the other, will be

found, upon a comparison of High with Low Dutch, to repeat itself also internally. The very

same mnemonic which there proved a

true guide, will substantially hold good

also here. The consonantal variations between the High Dutch on the one hand, and the Low Dutch on

the other, may be symbolised by

writing the German word famt over the

English word iame^ thus

fa m t t a me

EXTERNAL RELATIONS.

II

In this mnemonic, the final e of fame is there merely to make an English word of it, in order to

indicate that the S3nnbols, t, a, m,

in this place, are doing duty for the English

group, that is, the Low Dutch group, in the comparison; while the letters fa, tn, t, which form a

German word, represent the High Dutch

side of the comparison. The

combination of fa is useful as a reminder that in High Dutch the sibilant f or g is the substitute

for an aspirated dental (such as our

/^) which that language does not

possess.

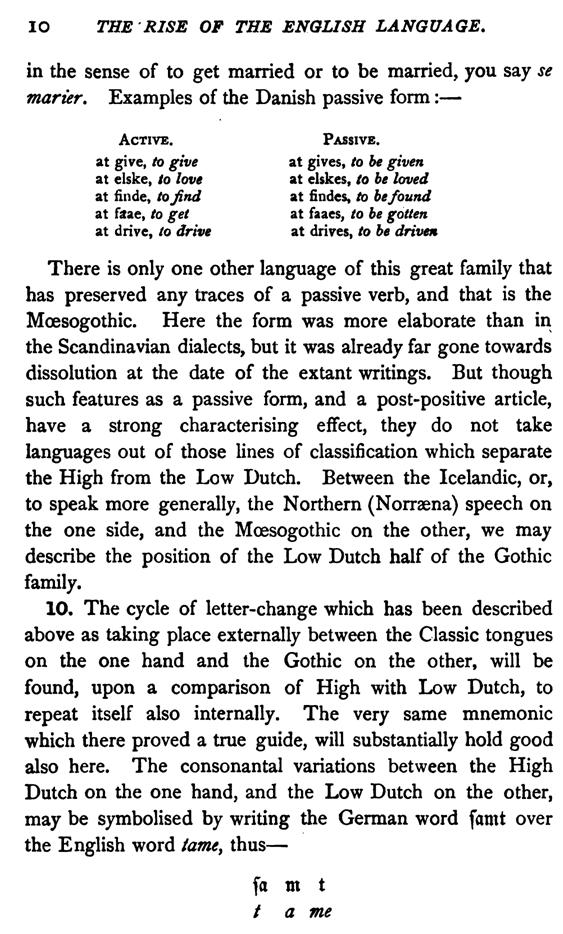

The action of this law is most readily exhibited with the dentals, because in these we can employ

modem German as the representative of

High Dutch. The first group illustrates

the law that where the Low Dutch has a tenuis, the High Dutch has an aspirate (or the sibilant

which supplies their want of a dental

aspirate), and this law is represented by the

formula

N.H.D. or German.

3e^tt

3tel

3t«ttttfr

Bunben

3tel^m

3eu(j

3unge

3al^n

3wei

3a^rf

3etc]^cn

Serrm

®?t

T

(ESOGOTHIC.

English.

Taihiin

Ten

Til

TiJl

Timr

Timber

Tindan

Tinder

Tiuhan

Teen (A.S.)

Tatd

Toy

Tuggo

Tongue

Tunthtus

Tooth

Tval

Two

Tagr

Tear

Taikns

Token

Tairan

Tear

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6019) (tudalen 011)

|

12

THE RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

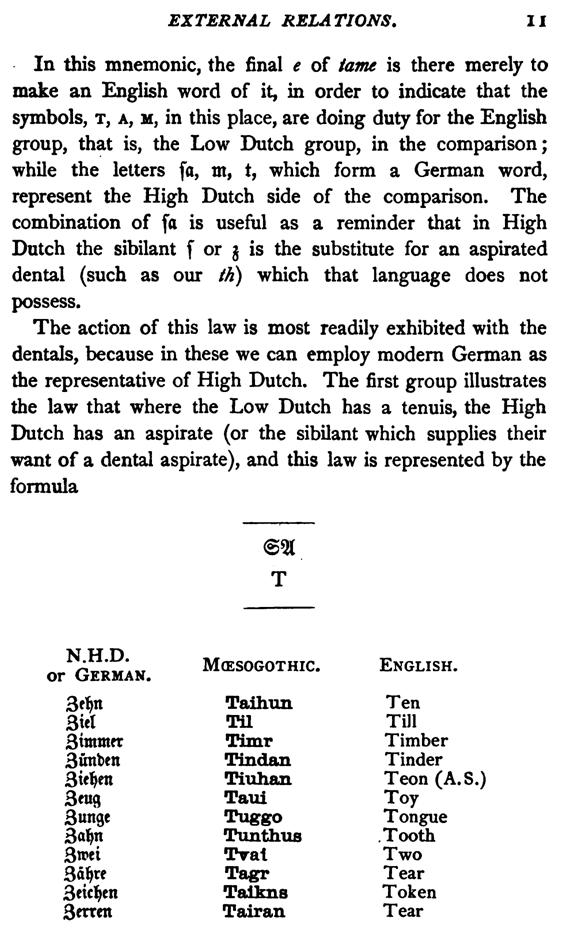

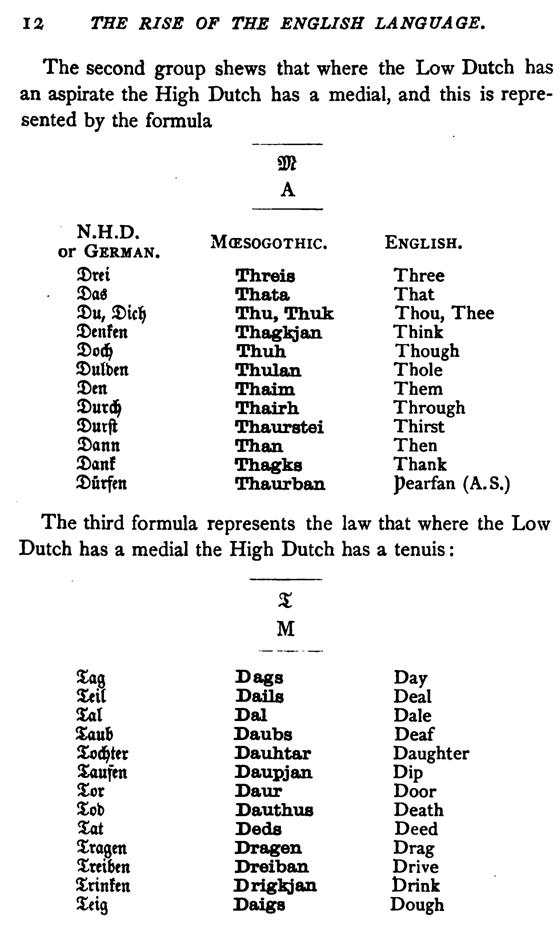

The second group shews that where the Low Dutch has an aspirate the High Dutch has a medial,

and this is represented by the formula

«ro

A

N.H.D.

or German.

MCESOGOTHIC.

English.

JDrei

Threis

Three

S)a«

Thata

That

JDu, 2)ic^

Thu, Thuk

Thou, Thee

JDcnfen

Thagkjan

Think

SDod^

Thuh

Though

JDulben

Thulan

Thole

JDctt

Thaim

Them

2)urd^

Thairh

Through

JDurjl

Thaurstei

Thirst

2)ann

Than

Then

2)anf

Thagks

Thank

2)urfen

Thaurban

pearfan (A.S.)

The third formula represents the law that where the Low Dutch has a medial the High Dutch has a

tenuis :

% M

2:a9

Dags

Day

Xeil

Dails

Deal

%oX

Dal

Dale

%QXA

Daubs

Deaf

Xod^ter

Dauhtar

Daughter

^ufen

Daupjan

Dip

%ex

Daur

Door

Xob

Dauthus

Death

%Qi

Deds

Deed

Xragen

Dragen

Drag

Xreiben

Dreiban

Drive

Xrinfen

Driglsjan

Drink

Xeig

Daigs

Dough

EXTERNAL RELATIONS.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6020) (tudalen 012)

|

13

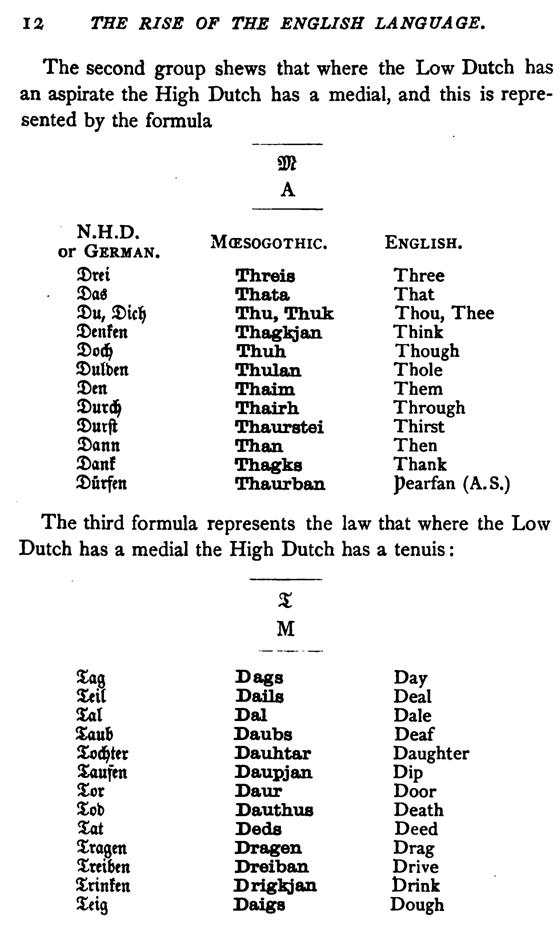

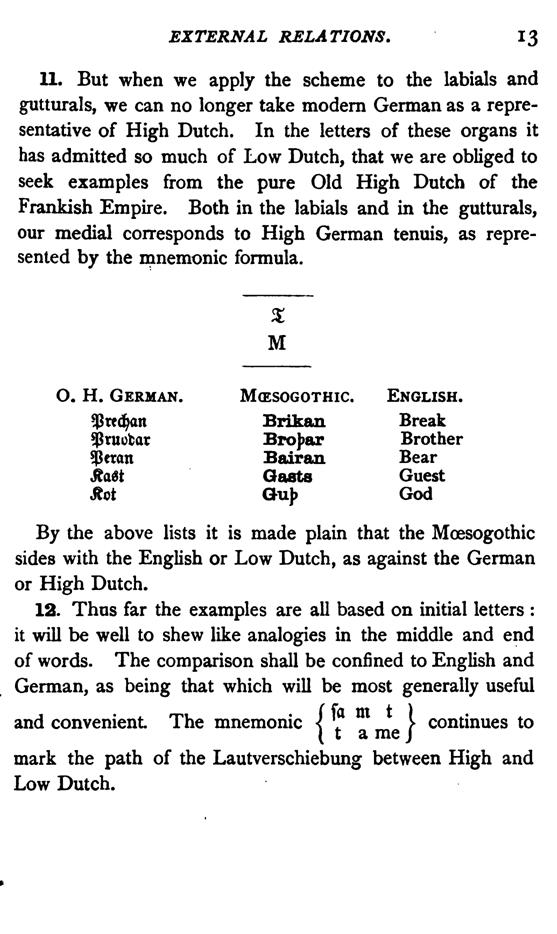

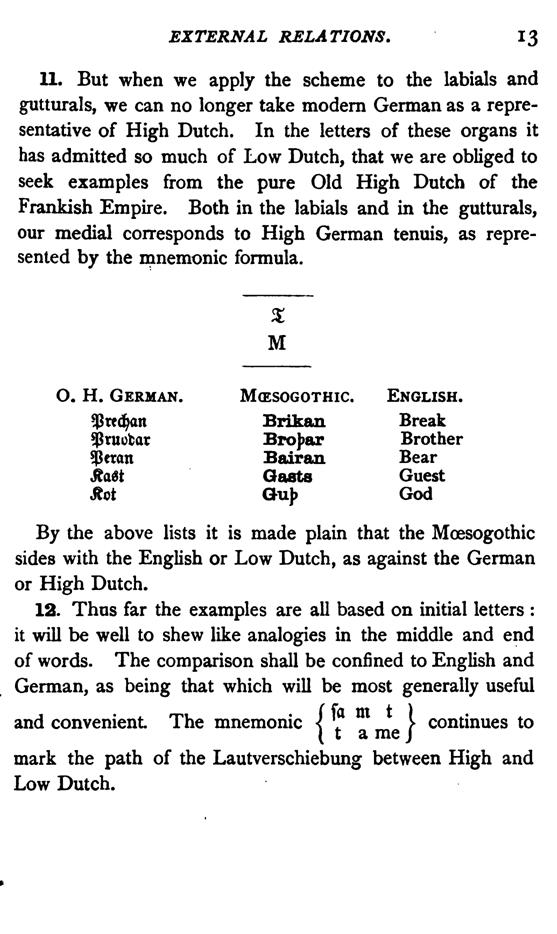

11. But when we apply the scheme to the labials and gutturals, we can no longer take modem

German as a representative of High Dutch. In the letters of these organs

it has admitted so much of Low Dutch,

that we are obliged to seek examples

from the pure Old High Dutch of the

Prankish Empire. Both in the labials and in the gutturals, our medial corresponds to High German

tenuis, as represented by the mnemonic formula.

M

0. H. German.

MffiSOGOTHIC.

English.

$re^n

Brika.n

Break

$ruotar

Bro})ar

Brother

$etan

Bairan

Bear

^a6t

Gaats

Guest

^ot

Gu^

God

By the above lists it is made plain that the Moesogothic sides with the English or Low Dutch, as

against the German or High Dutch.

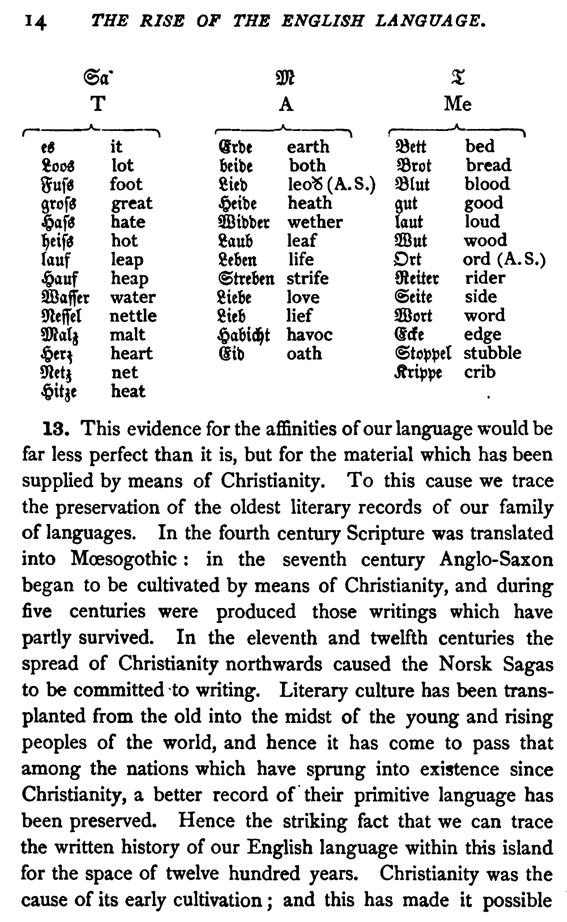

12. Thus far the examples are all based on initial letters : it will be well to shew like analogies in

the middle and end of words. The

comparison shall be confined to English and

German, as being that which will be most generally useful

and convenient The mnemonic \ \ > continues to

( t a me J

mark the path of the Lautverschiebung between High and

Low Dutch.

|

|

|

|

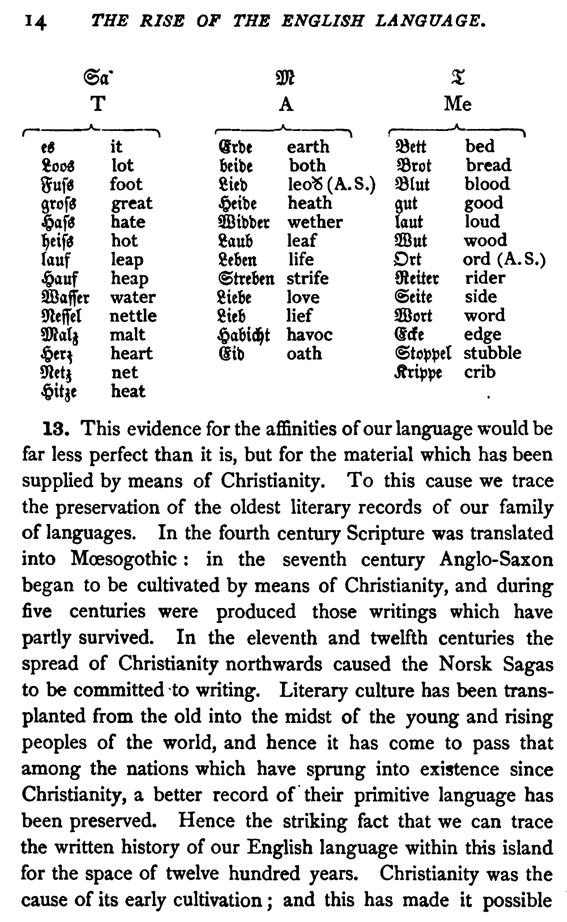

|

(delwedd E6021) (tudalen 013)

|

14

THE RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

®a-

a^^

X

T

A

Me

e« it

drbe

earth

$8ctt

bed

«oo« lot

Bcibe

both

S3rot

bread

guf« foot

fileb

leo«(A.S.)

«(ut

blood

grof« great

^etbe

heath

gut

good

^af^ hate

aiJibber

wether

laut

loud

^cip hot

«auB

leaf

ai^ut

wood

lauf leap

ScBctt

life

Drt

ord (A.S.)

J&auf heap

(Streben

strife

(Reiter

rider

Gaffer water

8icbe

love

eeite

side

0leffel nettle

8teB

lief

mcxt

word

3»alj malt

^abid^t

havoc

mt

edge

$er^ heart

@ib

oath

^tcp)ptl stubble

snctj net

^ip)pt

crib

^itge heat

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6022) (tudalen 014)

|

13.

This evidence for the affinities of our language would be far less perfect than it is, but for the

material which has been supplied by

means of Christianity. To this cause we trace

the preservation of the oldest literary records of our family of languages. In the fourth century

Scripture was translated into

Moesogothic : in the seventh century Anglo-Saxon began to be cultivated by means of Christianity,

and during five centuries were

produced those writings which have

partly survived. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the spread of Christianity northwards caused

the Norsk Sagas to be committed to

writing. Literary culture has been transplanted from the old into the midst

of the young and rising peoples of the

world, and hence it has come to pass that

among the nations which have sprung into existence since Christianity, a better record of their

primitive language has been preserved.

Hence the striking fact that we can trace

the written history of our English language within this island for the space of twelve hundred years.

Christianity was the cause of its

early cultivation ; and this has made it possible

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6023) (tudalen 015)

|

EXTERNAL RELATIONS. 1 5

for us to follow back the traces of our language into a far higher relative antiquity than that in

which the languages of Greece and Rome

first begin to emerge into historic view.

14. This has been very generally the case with the Christian nations of the

world. Their literature begins with their

conversion; and but for that event it would have been long delayed. The rude tribes of the distant

islands have now, by means of the

missionaries, the best books of the world

translated into their own tongues; and this at a stage of their existence in which they could not

of themselves produce a written

record. How carefully the Moesogothic

language was considered and adapted to the expression of Scripture, becomes manifest to the

philological student, when he examines

those precious relics of the fourth century which bear the name of Ulphilas. Here we often

meet the very words with which we are

so familiar in our English Bible, but

linked together by a flexional structure that finds no parallel short of Sanskrit. This is the

oldest book we can go back to, as

written in a language like our own. It

has therefore a national interest for us ; but apart from this, it has a nobility and grandeur all

its own, being one of the finest

specimens of ancient language. It is

by this, and this alone, that we are able' to realise to how high a pitch of inflection the speech of

our own race was once carried.

Inflections which in German, or even in

Anglo-Saxon, are but fragmentarily preserved, like relics of an expiring fashion, are there seen

standing forth in all their archaic

rigidity and polysyllabicity.

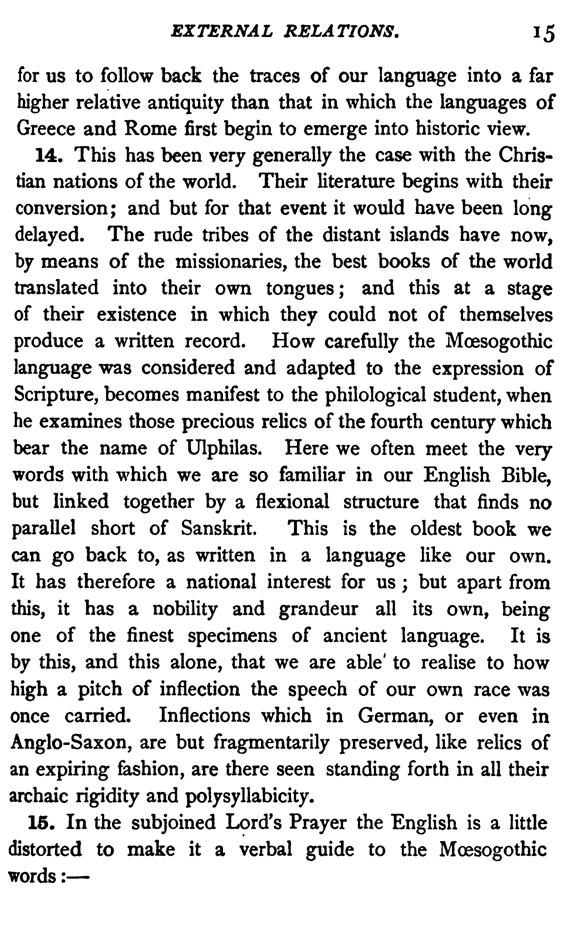

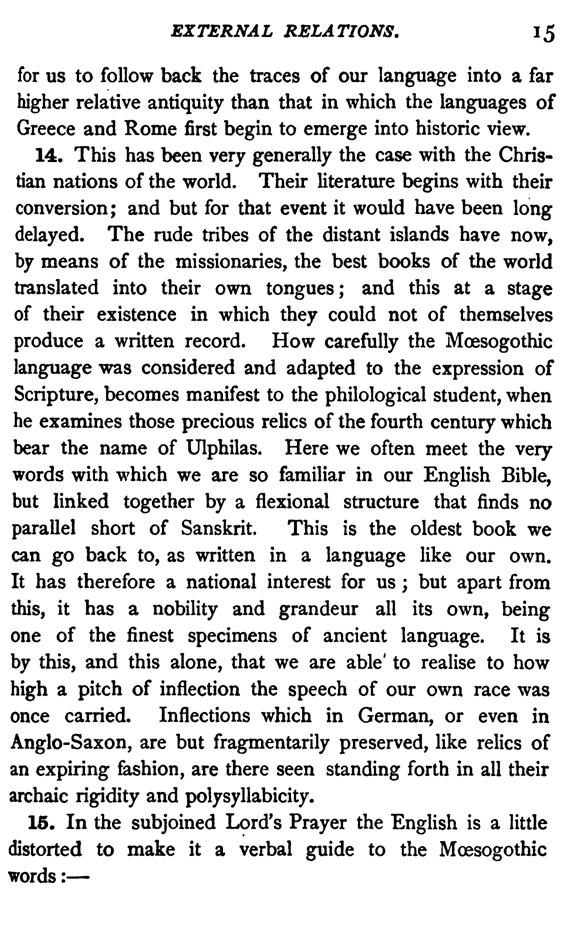

16. In the subjoined Lord's Prayer the English is a litde distorted to make it a verbal guide to the

Moesogothic words :

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6024) (tudalen 016)

|

l6 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

THE LORD'S PRAYER.

From the Mcesooothic Version of Ulphilas ; made about a.d. 565.

Aivaggelyo thairh Matthaiu. Gospel

through Matthew,

Atta unsar thu in himinain Father our

thou in heaven

Veilmai namo thein Be-hallowed name

thine

Kvimai thiudinassus theins Come

kingdom thine

Vairthai vi]ja theins. svd in himlTia yah ana airthai Be-done will thine as in heaven yea on

earth

Hlaif unsarana thana sinteinan gif una himma daga Loaf our the continuous give us this day.

Yah aflet uns thatei sknlans siyaima

Vea off-let us that-which owing we4>e

Svasve yah veis afletam thaim skulam unsaraim

So-as yea we offAet those debtors ours

Yah ni briggais uns in fraistubnyai

Vea not bring us in temptation

Ak lausei uns af thamma ubilin But

loose us of the evil

ITnte theina ist thiudangardi For

thine is kingdom

Yah mahts Yah vulthus Fea might Yea

glory

In aivins. Amen. In eternity. Amen,

16. The Low Dutch family of languages falls into two natural divisions, the Southern or Teutonic

Platt-Deutsch, and the Northern or

Scandinavian. It was at the point of

junction between these halves at the neck of the Danish

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6025) (tudalen 017)

|

EXTERNAL

RELATIONS. 1 7

peninsula, along the banks of the Elbe, and along the southwest coasts of the

Baltic that our continental progenitors

lived and spoke.

17. The Saxons were a border people, and spoke a Low Dutch strongly impregnated with

Scandinavian associations. But the

more we go back into the elder forms on either side, the more does it seem to come out clear,

that our mother tongue is, in

fundamentals, to be identified with the P/a/fDeutsche the dialect of the

Hanseatic cities, the dialect which

has been erected into a national language in that which we call the Dutch, as spoken in the kingdom of

the Netherlands. The people of Bremen

call their dialect Nieder Sdchisch, i. e.

Lowland Saxon ; and the genuine original * Saxony' of European history was in this part, namely,

the middle and lower biet of the Elbe.

The name of * Saxon* has always

adhered to our nation, though we have seemed almost as if we had been willing to divest ourselves

of it. We have called our country

England, and our language English : yet

our neighbours west and north, the Welsh and the Gael, have still called us Saxons, and our language

Saxonish. It has become the literary

habit of recent times to use the term

* Saxon' as a distinction for the early period of our history and language and literature, and to reserve

the term

* English' for the later period. There is some degree of literary impropriety in this, because the

Saxons called their own language

Englisc. On this ground some critics insist

that we should let the word English stand for the whole extent of our insular history, which they

would divide into Old English, Middle

English, and New English. But on the

whole, the terms already in use seem bolder, and more distinct. They enable us to distinguish

between Saxon and Anglian; and they

also comprise the united nation under

Uie compound term Anglo-Saxon. As expressive of the

c

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6026) (tudalen 018)

|

1 8

THE RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

dominant power, it is not very irregular to call the whole nation briefly Saxon.

§ 2. Domestic relations.

18. We have no contemporary account of the Saxon colonisation. The story which Bseda gives

us in the eighth century, is, that

there were people from three tribes, Angles,

Saxons, and Jutes. The latter were said to be still distinguishable in

Kent and the Isle of Wight; but, except in this statement, we have lost all trace of the

Jutes. The Angles and Saxons long

stood apart and distinct from one another ;

they had each a corner of their own. The Anglians occupied the north

and east of England, and the Saxons the

south and west. The line of Watling Street, running from London to Chester, may be taken as the

boundary line between these races,

whom we shall sometimes speak ol

separately, and sometimes combine, according to prevalent usage, either under the joint name of

Anglo-Saxons, oi under the dominant

name of Saxons.

When the Anglo-Saxons began to make themselves masters of this island, they found here a

population which is known in history

as the British race. This people spoke the language which is now represented by the Welsh. It

was an ancieni Keltic dialect somewhat

tinctured with Latin. The BritonJ had

been in subjection to Roman dominion for a space o between three and four centuries. This

would naturally hav( left a trace upon

their language. And hence we find tha

of the words which the Saxons learnt from the Britons some are undoubted Latin, others are

doubtful whether the] should be called

Latin or Keltic. Of the first class are thosi

elements of local nomenclature, -Chester^ from castrum^ i fortified place Saxon form, ce aster :

street^ from strata^ i. e

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6027) (tudalen 019)

|

DOMESTIC

RELATIONS. , 1 9

*via strata' = a causeway Saxon form, street. Port, a word derived from the Latin porfa, a gate,

signified in Saxon times just *a town,

a market-town:' this is the sense of it in

such a compound as Newport Pagnell. Wall, Saxon weall, is through the same filtered process a

descendant of the Latin vallum, 2l

rampart: mt'le, Saxon mil, from the Latin

*mz'lia passuum/ a thousand paces, has lived through all the ages to our day, and we are the only people

of Western Europe who still make use

of this Roman measure of distance. The

French keep to their leagtte {It'eue), the

measure which they had in use before the Romans troubled them, the old Keltic leuga. In Saxon poetry

we find the old highways called by the

suggestive name of milpa^as, the

mile-paths. Carcern, a prison, is the Latin career, with the Saxon word ern, a building, mingled into

the last syllable : TiGOL, a tile, is

the Roman tegula. At this time, too, we

must have received the names of many plants and fruits, as PYRiGE, the pear, Latin pyrus,

19. Many of the words which pertain to the personal and social comforts of life, were in this

manner learnt at secondhand from Roman culture : as disc, a dish ; from his

handing of which a royal ofificer all

through the Saxon period bore the tide

of disc-J?egn, dish-thane.

When we consider that there was much originally in common between the Latin

and the Keltic, it is no matter of

surprise that after so long a period we should find it difficult to sift out with absolute distinctness the

words which are due to the British.

The most certain are those names of rivers

and mountains, and some elements in the names of ancient towns, which have been handed on from

Keltic times to ours. Thus the

river-name Avon is unquestionably British,

and it is the common word for river in Wales to this day. So again with regard to that large class of

river-names which

C 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6028) (tudalen 020)

|

20 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

are merely variations of the one name Isca Usk, Ux, Wis(in Wisbech), The

Wash, Axe, Exe, Esk (in the Lothians),

Ouse: all these are but many forms of one Keltic word, ut'sg, water ; which is found in usquehagh, the

Irish for eau-de-vie^ and in the word

whiskey. There are however, on our map,

a great many names of rivers and cities and mountains, of which, though so precise an account cannot

be rendered, it is generally concluded

that they are British because they

run back historically into the time when British was prevalent because they are not Saxon ^because, in

short, they cannot otherwise be

accounted for. Such are, Thames,

Tamar, Frome, Derwent, Trent, Tweed, Severn, and the bulk of our river-names.

20. In like manner of the oldest town- names, and some names of districts. The first syllable in

FFi'wchester appears, through the

Latin form of Venta^ to have been the same as

the Welsh gweni, a plain or open country. The first syllable in MancYiQ^itT is probably the old Keltic

man, place; just as it probably is in

the archaic name for Bath, Ak^-manchester. Fork is so called from the Keltic

river-name Eure ; from an elder form

of which came the old Latin form of the

city -name Ebur-acum. But often where the sense cannot be so plainly traced, we acquiesce in the

opinion that names are British,

because their place in history seems to require it. Such are, for instance, Keni^ London^

Gloucester.

We will add a few words that have a fair Keltic reputation, basket, bran, breeches, clout, crag, crock,

down, den, hog, manor , paddock, park,

wicket. The word moor, for wild or waste land, I imagine to be Keltic, but

naturalised by the Saxons on the

continent before the immigration.

It is very probable that a few Keltic words are still living on among us in the popular names of wild

plants. The cockle of our corn-fields

has been with great reason attributed

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6029) (tudalen 021)

|

DOMESTIC

RELATIONS. 21

to the Britons. The Saxon form is coccel, but the word is not found in the kindred dialects. This is

the more re* markable, because most of

the tree and plant names are common to

us with the German, Dutch, Danish, &c. The words alder, apple, ash, aspen, beam, bean,

beech, bere, birch, bloom, blossom,

bramble, clover, corn, elm, flax, grass, holt, leek, lime, moss, nightshade, oak, radish,

reed, root, rye, shaw, thistle, thorn,

tree, way bread, weed, wheat, wood, wormwood,

wort, yarrow, yew, are more or less common to the cognate languages. This is not the case with

cockle, and therefore it may perhaps

be British. Another plant-name, which is probably British, is willow. This

may well be traced to the Welsh helig

as its nearer relative, without interfering with the more distant claims of saugh, sallow,

salix. Whin also, and furze, have

perhaps a right here. With strong probability also may we add to this

botanical list the terms hisk^ haw,

and more particularly cod, a word that merits

a special remark. In Anglo-Saxon times it meant a bag, a purse or wallet \ Thence it was applied

to the seedbags of plants, as pease-cod. This seems to be the Welsh cwd. The puff-ball is in Welsh cwdy-mivg,

bag of smoke. Owen Pughe quotes this

Welsh adage : * Egor dy gwd pan

gaech borchell'; i.e. *Open thy bag when canst get a pig!* an expression which for

picturesqueness must be allowed the

palm over our English proverb * Never say no to a good offer.' What establishes the British

origin of this word is the large connection

it has in Welsh, and its appearance also in Brittany. Thus in Welsh there is

the diminutive form cydyn, a little

pouch, and the verb cuddio, to hide, with

many allied words ; in Breton there is kSd, pocket.

' See a spirited passage in the Saxon Chronicle of Peterborough, a.d. i

131, and my note there.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6030) (tudalen 022)

|

22 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

The compound cock-boat \s probably a bilingual compound of which the first part is the Welsh avch,

a boat, a wore which has several

derivatives in Welsh.

Bard is unquestionably British, and so is gletiy and \\\it\f\^t flannel ) but

then these made their entry later, and dc

not belong to the present subject, which is the immediate influence of the British on the Saxon,

21. We can never expect to know with anything like precision what were the

relations of the British and Saxor

languages to each other and to the Latin language, until eacfc has been studied comparatively to a degree

of exactness beyond anything which has

yet been attempted. All 'the Gothic

dialects must be taken into comparison on the one hand, and all the Keltic dialects on the

other. The interesting question for us

is Haw far the British population at largi

was Romanised ? Some think that habits of speaking Latin were almost universal, and they

appeal to the rude inscribed stones of

the earlier centuries which are found in

Wales, and which are in a Latin base enough to be attributed to

illiterate stonemasons. These stones are called in evidence to shew that a knowledge of

Latin was diffused through the whole

community. On this view, which receives support also from the number of Latin

words in Welsh, the arrival of the

Saxons prevented this island from

becoming the home of a Romanesque people like the French or Spanish.

22. The British language as now spoken in Wales is called, by those who speak it, Cymraeg; but

the AngloSaxons called it Wylscy and the people who spoke it th&y called WalaSy which we have modernised into

Wales and Welsh. So the Germans of the

continent called the Italians and

their language SBelfd^. At various points on. the frontiers of our race, we find them giving

this name to the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6031) (tudalen 023)

|

INFLUENCE

OF THE CHURCH ON THE LANGUAGE.

2^

conterminous Romance-speaking people. This is the most probable account of the names Wallachia^

the Walloons in Belgium, and the

Canton Wallis in Switzerland. Oa this

principle we called the Romanised Britons, and the Germans called the Italians, by the same

name Welsh. In Acts X. I, where we

read ' Cornelius, a centurion of the band

called the Italian band,* Luther's version has * Cornelius, ein Hauptmann von der Schaar, die da heisst die

Welsche.' The French, who were such

unwelcome visitors and settlers in this

country in the reign of Edward the Confessor, are called by the contemporary annalist * f>a welisce

men.' When Edward himself came from

the life of an exile in France, he was said

by the chronicler to have come ' hider to lande of weallande.* It is the same word which forms the last

syllable in Cornwall, for the Kelts who dwelt there were by the Saxons named the Walas of Kernyw.

The word was weal or wealh^ feminine wylen ; and it is an illustration of the servile condition to

which the old inhabitants were

reduced, that the words wealk and zuylen came to signify male and female slave.

§ 3. hifluence of the Church on the Language,

23. About the year a.d. 6oo, Christianity began to be received by the Saxons. The Jutish kingdom

of Kent was the first that received

the Gospel, and the Church was supreme

in Kent before Northumbria began to be converted. Yet the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria gained

afterwards the leading position as a

Christian nation in Saxondom ; and

being distinguished for learning and literature as well as for zeal, this people exerted a permanent

influence on the national language.

Intimately connected with this is the

political supremacy which the northern kingdom enjoyed

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6032) (tudalen 024)

|

24 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

in this island for a hundred years. It is evident that there was great and substantial progress in

religion, civilisation, and learning ;

of which fact the permanent memorial is the name and works of Baeda, who died in 735, after

having seen the decline of the

greatness of his people.

Canterbury was the metropolis of Christianity, but the kingdom of Northumbria was its most

powerful seat. It was the attachment

of this northern Church to the Roman

interest that effectually put a stop to the progress of the Scotian discipline in this island. The

power of this Anglian nation and the

admiration she excited in her

neighbours, caused them to emulate her example, to read her books, to form their language after

hers, and to call it ENGLisc. The Angles

first produced a cultivated bookspeech, and they had the natural reward of

inventors and pioneers, that of setting

a name to their product. Of all the

losses which are deplored by the investigator of the English language, perhaps there is none

greater than this, that the whole

Anglian vernacular literature should

have perished in the ravages of the Danes upon the Northhumbrian

monasteries. Of the existence of such a native literature there is no room for doubt.

Baeda tells us of such ; and he

himself was occupied on a translation when he died. Thus the obscure name of Angle emerged into

celebrity, and furnished us with the

comprehensive names of English and

England, which have continued to designate our country, tongue, and nation. The name of England is

confined by geographic limits; but the

name of English has widened with the

growing area of the countries, colonies and dependencies that are peopled or

governed by the children of our

tongue.

24. The extant works of Baeda are all in Latin, but they afford occasional glimpses of information

about the spoken

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6033) (tudalen 025)

|

INFLUENCE

OF THE CHURCH ON THE LANGUAGE.

25

Englisc of his day. As for example, in the Epistle to Ecgberhi^ he advises that prelate to make

all his flock leam by heart the Creed

and the Lord's Prayer. In Latin, if they

understand it, by all means, says he, but in their own tongue if they do not know Latin. Which, he adds,

is not only the case with laity, but

with clerks likewise and monks. And markedly

insisting on his theme, as if even then the battle of the vernacular had to be fought, he goes on

to give his reasons why he had often

given copies of translations to folk that

were no scholars, and many of them priests too.

One of his most interesting chapters is that in which he gives the traditional story of the

vernacular poet Caedmon, who by divine

inspiration was gifted with the power of song, for the express purpose of rendering the

Scripture narratives into popular

verse. The extant poems of the Creation and

Fall and Redemption, which are preserved in archaic Saxon verse, are attributed to this Caedmon ; and

it is possible that they may be his

work, having undergone in the process

of copying a partial modification. We gather from the account in Baeda, that the practice of

making ballads was in a high state of

activity, and also that vernacular poetry was

used as a vehicle of popular instruction in the seventh century in Northumbria. And it is

interesting to reflect that in all our

island there is no district which to this day has an equal reputation for lyric poetry, whether

we think of the mediaeval ballads, or

of Burns, or of the Minstrelsy of the

Scottish Border.

26. It was in the monastery of Whitby, under the famous government of the abbess Hilda, that the

first sacred poet of our race devoted

his life to the vocation to which he had been

mysteriously called. If something of the legendary hangs over his personal history, this only shews

how strongly his poetry had stirred

the imagination of his people. A nation

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6034) (tudalen 026)

|

26 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

that could believe their poet to be divinely called, was the nation to produce poets, and to elevate the

genius of their language. Such was the

Anglian kingdom of Northumbria, and

here it was that our language first received high cultivation.

It is remarkable that, while the peoples of the southern and western and south-eastern parts of the

kingdom continually called themselves Saxons (witness such local names as Wessex, Essex, Sussex, Middlesex), yet

they never appear in any of their

extant literature to call their language Seaxisc, but always Englisc^ The explanation of this

must be sought, as I have already

indicated, in that early leadership

which was enjoyed by the kingdom of Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries. The

office of bretwalda, a kind of

elective chieftainship of all Britain, was held by several Northumbrian kings in

succession. How high this title must

have sounded in the ears of cotemporaries

may be imagined from the fact that it is after the same model as their name for the Almighty. The

latter was ALWALDA, the All-wielding.

So Bretwalda was the wielder of

Britain, or the Emperor of all the States in Britain.

26. The culture of Northumbria overlived the term of its political supremacy. For a century and a

half the northern part of the island

was distinguished by the growth of a native

Christian literature, and of Christian art. Two names there are prominently associated with this

Northumbrian school, which mark the

extremities of the brightest part of its duration. The first is Benedict

Biscop, an Anglian by birth, who made

five visits to Rome, and founded the monastery ol

^ Yet we find the Latin equivalent of Seaicisc, as in Asser's Life of

Alfred, where the vernacular is called

Saxonica lingua. Asser however was a Welshman. Also in Cod. Dipl. 241, * in

commune silfa q' nos saxonice in gemennisse dicimus.' Also 833, 867.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6035) (tudalen 027)

|

INFLUENCE

OF THE CHURCH ON THE LANGUAGE.

37

Wearmouth in 672. The other was Alcuin, by whose aid Charlemagne laid the foundations of

learning in his vast dominions. Alcuin

died in 805.

This new vernacular literature of Northumbria perished in the ravages of the Danes, and not enough

remains to give an intimation of what

is lost. Meantime, the old mythic

songs still held their own in the south, where no strong growth of Christian literature appeared to

contest the ground against them. But

even these could not escape without

some colouring from the new religion and its sacred literature, and we

may assign the eighth century as the time when the Beowulf received those last superficial

touches which still arrest the

reader*s eye as masking or softening the heathendom of the poem. Alfred was a

lover of this old national poetry.

With the mention of Alfred's name, we enter upon a comparatively modem era of

the language, and quit the obscurity

of the pre-Danish period. Wessex, or the country of the West Saxons, becomes the arena of our

narrative henceforth, and the Anglian

does not claim notice again until the fourteenth century, when that dialect

had shaped itself into a new and

distinct national language for the kingdom of Scotland. Barbour in his poem of the Brtice

determined the character of modern

Scottish, and cast it in a permanent mould, just as his contemporary Chaucer did for our

English language. Again, in the

eighteenth century there was a brilliant revival of the Anglian dialect, out

of which came the poetry of Allan

Ramsay and of Robert Bums, and the dialogues

in * brad Scots,' which so charmingly diversify the novels of Sir Walter Scott. It is odd that this

language, which is Anglian tinged with

Norsk, should have received the Keltic

name of * Scotch ' from the Scotian dynasty which mounted the Anglian throne; and that in taking a

modern name

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6036) (tudalen 028)

|

28 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

from its northern neighbours it should have furnished a geographical parallel to the adoption of

the name of * English ' by the West

Saxons.

27. Wessex had not been entirely destitute of Christian learning during the period of Northumbrian

pre-eminence. Aldhelm is the first

great name in southern literature. He

died in a.d. 709. He translated the Psalms of David into his native tongue, and composed popular

hymns to drive out the old pagan

songs. But though we can point to Aldhelm,

and one or two other names of cultivated men in Wessex, they are exceptions to the general rudeness

of that kingdom before Alfred's time.

Wessex had been distinguished for its

military rather than for its literary successes. Learning had resided northward. But in the ninth century

a great revolution occurred. Northumbria and Mercia fell into the hands of the heathen Danes, and culture was

obliterated in those parts which had

hitherto been most enlightened. It was

Alfred's first care, after he had won the security of his kingdom, to plant learning. We have it in

his own words, that at his accession

there were few south of Humber who

could understand their ritual, or translate a letter from Latin into Englisc ; * and,' he adds, ' I ween

there were not many beyond Humber

either ' pointing to the heathen darkness

in which the north was then shrouded.

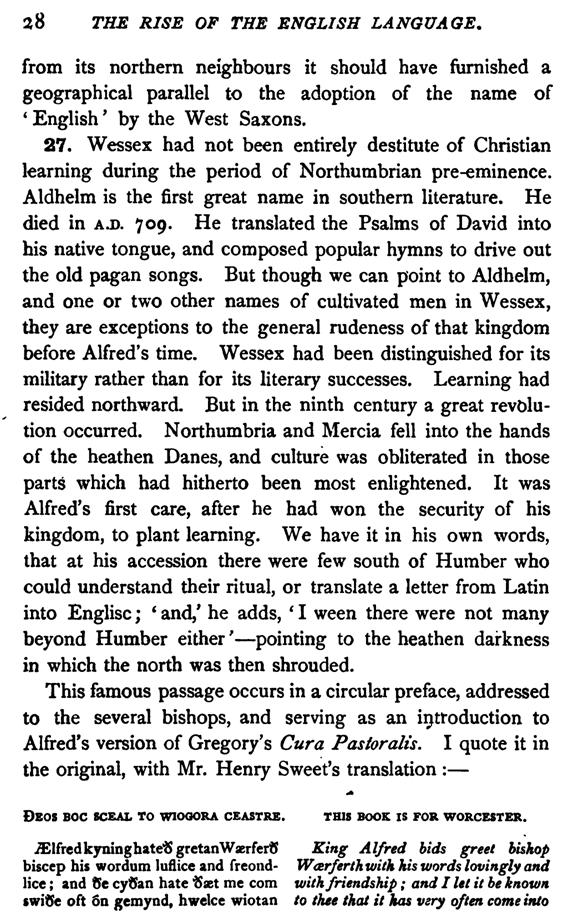

This famous passage occurs in a circular preface, addressed to the several bishops, and serving as an

irjtroduction to Alfred's version of

Gregory's Cura Pasioralts. I quote it in

the original, with Mr. Henry Sweet's translation :

DEOS BOC SCEAL to WIOOORA CEASTRE. this book is for WORCESTER.

Alfred kyning hate's grctanWacrferC King Alfred bids greet bishop

biscep his wordum luflice and freond- Warferthwith his words lovingly and

lice ; and 9e cyOan hate ISxt me com with friendship ; and I let it be known

swiOe oft 6n gemynd, hwelce wiotan to thee that it has very often come into

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6037) (tudalen 029)

|

INFLUENCE

OF THE CHURCH ON THE LANGUAGE.

29

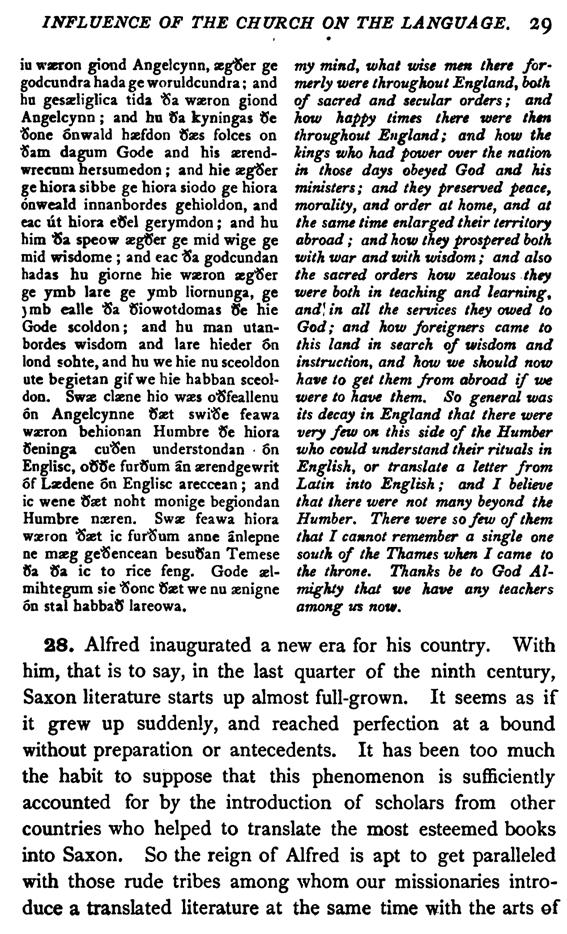

iu wanron giond Angelcynn, sBgt»er ge my mind, what wise men there for-

godcundra hada ge woruidcundra ; and merly were throughout England, both

ha geszliglica tida t$a waeroa giond of sacred and secular orders ; and

Angelcynn ; and hn t$a kyningas 0e how happy times there were then

"$006 6nwald haefdon iSxs folces on throughout England; and how the

"Sam dagum Gode and his xrend- kings who had power over the nation

wrecnm hersumedon ; and hie aeg^er in those days obeyed God and his

gehiorasibbe ge hiora siodo ge hiora ministers; and they preserved peace,

onweald innanbordes gehioldon, and morality, and order at home, and at

eac lit hiora eCel gerymdon ; and hu the same time enlarged their territory

him "Sa speow aegf^er ge mid wige ge abroad ; and how they prospered

both

mid wisdome ; and eac 9a godcundan with war and with wisdom ; and also

hadas hu giorne hie waeron aeg'Ser the sacred orders how zealous they

ge ymb lare ge ymb liornunga, ge were both in teaching and learning,

) mb ealle iSz t^iowotdomas 9e hie and] in all the services they owed to

Gode scoldon; and hu man utan- God; and how foreigners came to

hordes wisdom and lare hieder 5n this land in search of wisdom and

lond sohte, and hu we hie nu sceoldon instruction, and how we should now

ute begietan gif we hie habban sceol- have to get them from abroad if we

doQ. SwaB claene hio waes o'Sfeallenu were to have them. So general was

on Angelcynne ©act swi'Se feawa its decay in England that there were

wacron behionan Humbre t5e hiora very few on this side of the Humber

Seninga cut$en understondan 6n who could understand their rituals in

Englisc, oCCe furSum an aerendgewrit English, or translate a letter from

6f Lzdene on Engh'sc areccean ; and Lcuin into English ; and I believe

ic wene tJset noht monige begiondan that there were not many beyond the

Humbre naeren. Swae feawa hiora Humber. There were so few of them

waeron "Saet ic furtSum anne anlepne tlmt I cannot remember a single one

ne maeg ge'Sencean besu&an Temese south of the Thames when I came to

8a t^a ic to rice feng. Gode aeU the throne. Thanks be to God Al-

mihtegum sie tSonc t^aet we nu senigne mighty that we have any teachers

on stal habbaO lareowa. among us now.

28, Alfred inaugurated a new era for his country. With him, that is to say, in the last quarter of

the ninth century, Saxon literature

starts up almost full-grown. It seems as if

it grew up suddenly, and reached perfection at a bound without preparation or antecedents. It has

been too much the habit to suppose

that this phenomenon is suflBciently

accounted for by the introduction of scholars from other countries who helped to translate the most

esteemed books into Saxon. So the

reign of Alfred is apt to get paralleled

with those rude tribes among whom our missionaries introduce a

translated literature at the same time with the arts of

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6038) (tudalen 030)

|

30 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

reading and writing. It has not been sufficiently considered that such translations are dependent on the

previous exercise of the native

tongue, and that foreign help can only bring up a wild language to eloquence by very slow

degrees. There is a vague idea among

us that our language was then in its

infancy, and that its compass was almost as narrow as the few necessary ideas of .savage life. A modern

Italian, turning over a Latin book,

might think it looked very barbarous ;

and perhaps even some moderate scholars have never appreciated to how great a power the Latin

tongue had attained long before the

Augustan era. Great languages are not

built in a day. The fact is that Wessex inherited a cultivated language from the north, and

that when they called their

translations Englisc and not Seaxisc, they acknowledged that debt. The

cultivated Anglian dialect became the

literary medium of hitherto uncultured Wessex ; just as the dialect of the Latian cities set the

form of the imperial language of Rome,

and that language was called Latin.

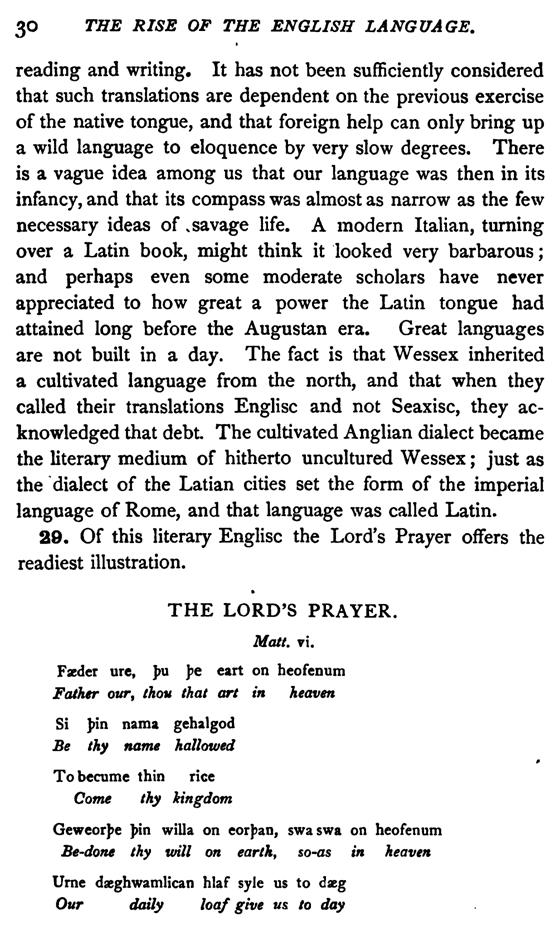

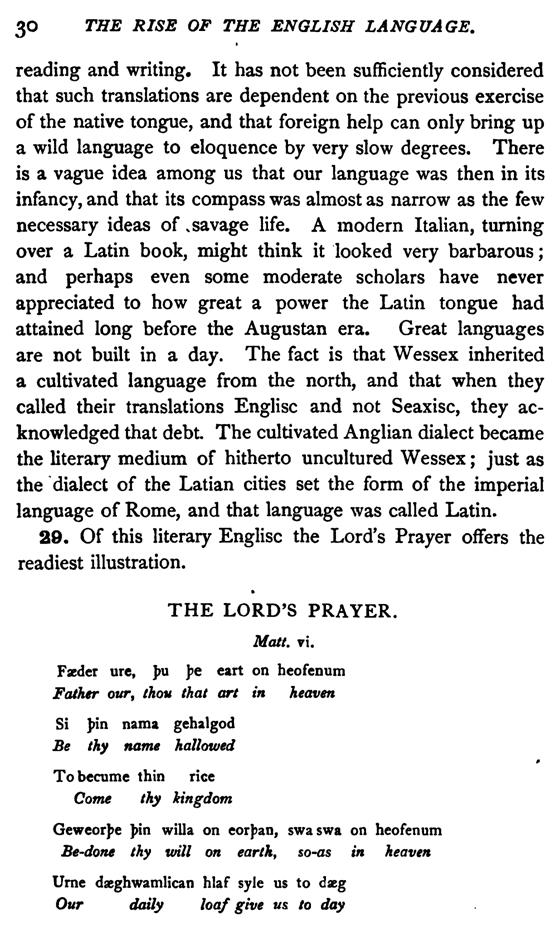

29. Of this literary Englisc the Lord's Prayer offers the readiest illustration.

THE LORD'S PRAYER.

Matt. VI.

Faeder ure, ]>u J^e eart on heofenum

Father our, thou that art in heaven

Si ]>in nama gehalgod Be thy name

hallowed

Tobecume thin rice Come thy kingdom

Geweor]}e ]>in willa on eor})an, swaswa on heofenum Be-done thy vnll on earthy sohis in heaven

Urae daeghwamlican hlaf syle us to dxg

Our daily loaf give u& to day

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6039) (tudalen 031)

|

CHARACTERISTICS

OF ANGLO-SAXON. 3I

And forgyf us ure gyltas, swa swa we forgifaj? urum gyltendum And forgive us our debts, so-as we forgive

our debtors

And ne gelsede |>u us on costnunge, ac alys us of yfle And not lead thou us into temptation^ but

loose us of evil

So]}lice. Soothly {Amen),

The period of West- Saxon leadership extends from Alfred to the Conquest, about a.d. 880 to a.d.

1066. These figures represent also the

interval at which Saxon literature was

strongest ; but its duration exceeds these limits at either end. We have poetry, laws, and annals before

880, and we have large and important

continuations of Saxon Chronicles

after 1066. Perhaps the most natural date to adopt as the close of Saxon literature would be a.d.

1154, the year of King Stephen's death,

the last year that is chronicled in

Saxon.

§ 4. Characteristics of Anglo-Saxon,

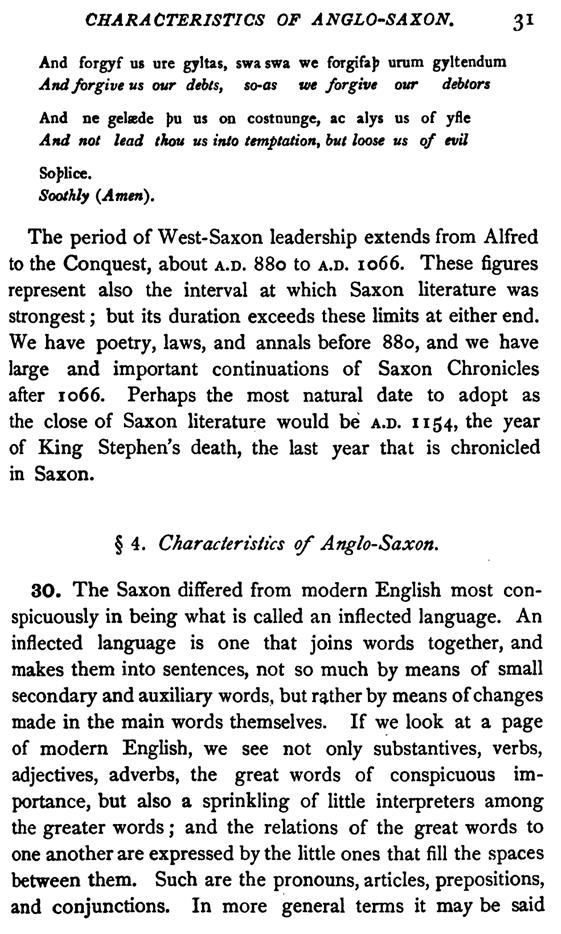

30. The Saxon differed from modern English most conspicuously in being what

is called an inflected language. An

inflected language is one that joins words together, and makes them into sentences, not so much by

means of small secondary and auxiliary

words, but rather by means of changes

made in the main words themselves. If we look at a page of modem English, we see not only

substantives, verbs, adjectives,

adverbs, the great words of conspicuous importance, but also a sprinkling of

little interpreters among the greater

words ; and the relations of the great words to one another are expressed by the little

ones that fill the spaces between

them. Such are the pronouns, articles, prepositions, and conjunctions. In more general terms it

may be said

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6040) (tudalen 032)

|

32 THE

RISE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

that the essence of an inflected language is, to express by modifications of form that which an uninflected

language expresses by arrangement of

words. So that in the inflected

language more is expressed by single words than in the noninflected.

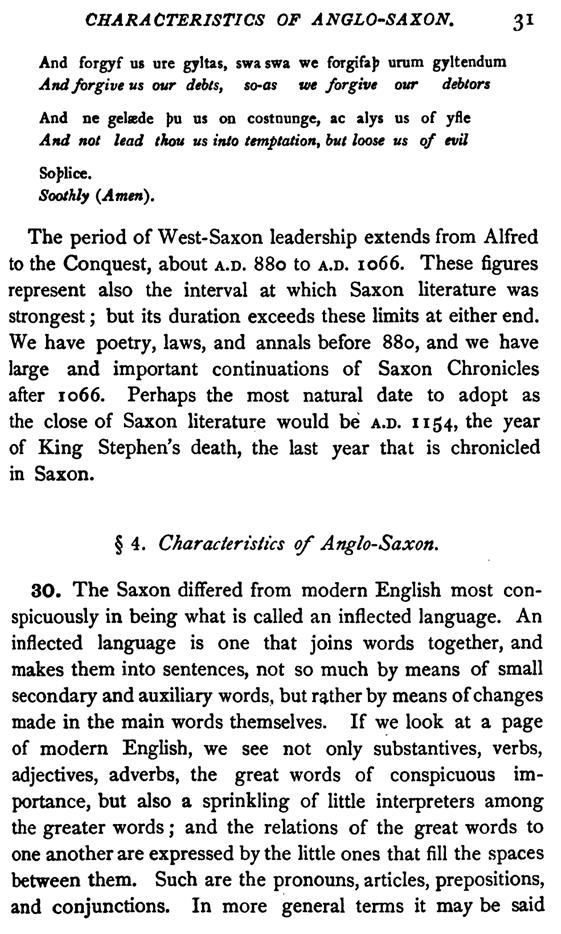

Take as an example these words of the Preacher, and see how differently they are

constructed in English and in Latin :

Eccles. iii,

Tempus nascendi, et tempos mo- A time io be born, and a time to riendi ; tempus plantandi, et tempus die ;

a time to plant, and a time to

evellendi quod plantatum est. pluck vp that which is planted.

Tempus occidendi, et tempus sa- A time to kill, and a time to heal ; nandi; tempus destruendi, et tempus a time

to break down, and a time to

aedificandi. build up,

Tempus flendi, et tempus ridendi ; A time to weep, and a time to tempus plangendi, et tempus saltandi. laugh

; a time to mourn, and a time

to dance,

Tempus spargendi lapides, et tem- A time to cast away stones, and pus colligendi. a time to gather stones

together.

There are no words in the Latin answering to the words which are italicised in the English version

a, to^ be, up, that^ away, together

yet the very sense of the passage

depends upon them in English, often to such a degree that if one of these were to be changed, the

sense would be completely overturned.

The Latin has no words corresponding to these symbols, but it has an

equivalent of another kind. The

terminations of the Latin words undergo

changes which, are expressive of all these modifications of sense ; and these changes of form are

called Inflections,

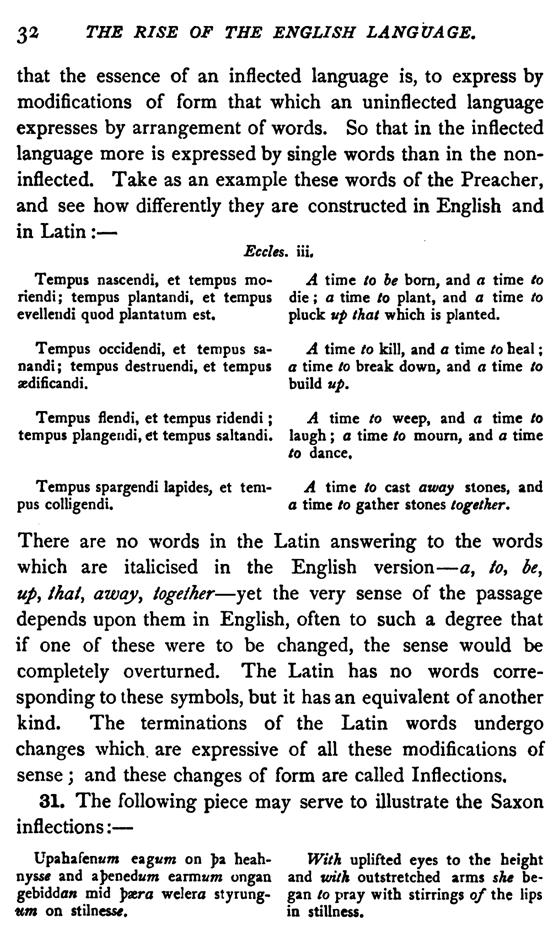

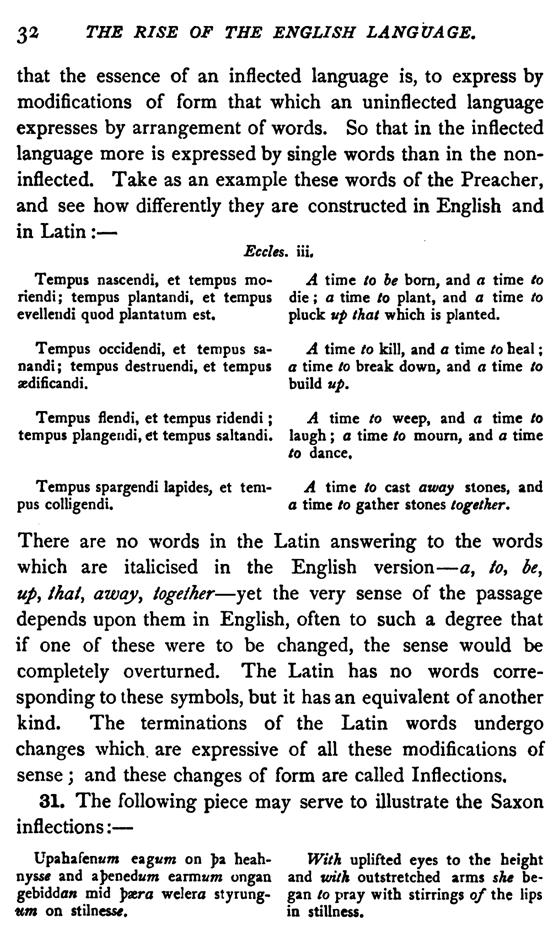

31, The following piece may serve to illustrate the Saxon inflections :

Upahafent/m eagwrn on ))a heah- With uplifted eyes to the height

nys5tf and a]>enedt/m earmvm ongan and with outstretched arms &he be-

gebiddan mid ]>aera wclera styrung- gan to pray with stirrings of the lips

um on stilnes5«. in stillness.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6041) (tudalen 033)

|

CHARACTERISTICS

OF ANGLO-SAXON. 33

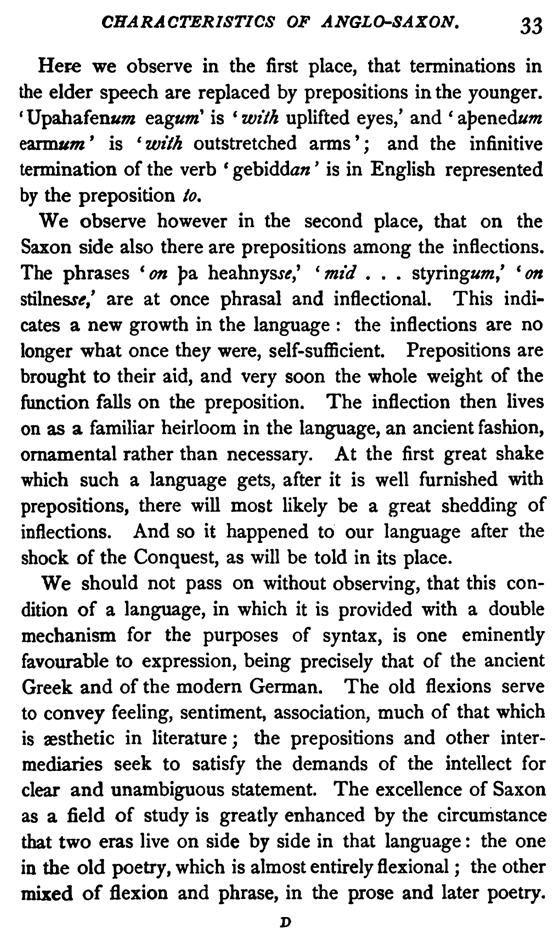

Here we observe in the first place, that terminations in the elder speech are replaced by

prepositions in the younger. '

\Jipsh3,fenum e2igum' is * wM uplifted eyes/ and ' 2]>enedum t^nnum* is 'wM outstretched arms'; and the

infinitive termination of the verb *

gebidda« ' is in English represented

by the preposition /o.

We observe however in the second place, that on the Saxon side also there are prepositions

among the inflections. The phrases *

on j?a heahnysj^,' ' mtd . . . stynngumy* ^ on stilnesj^,' are at once phrasal and

inflectional. This indicates a new growth in the language : the inflections

are no longer what once they were,

self-suflScient. Prepositions are

brought to their aid, and very soon the whole weight of the fimction falls on the preposition. The

inflection then lives on as a familiar

heirloom in the language, an ancient fashion,

ornamental rather than necessary. At the first great shake which such a language gets, after it is

well furnished with prepositions,

there will most likely be a great shedding of

inflections. And so it happened to our language after the shock of the Conquest, as will be told in

its place.

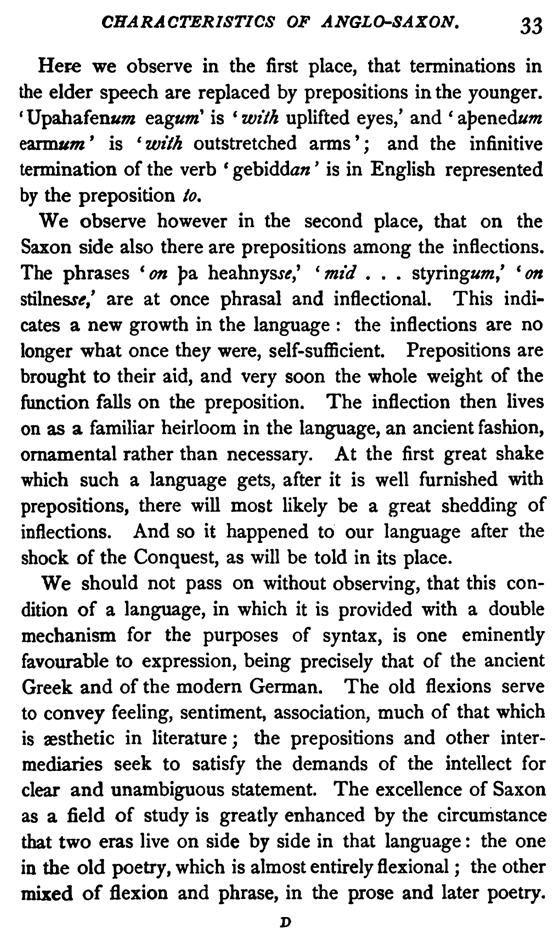

We should not pass on without observing, that this condition of a language,

in which it is provided with a double

mechanism for the purposes of syntax, is one eminently favourable to expression, being precisely

that of the ancient Greek and of the

modern German. The old flexions serve

to convey feeling, sentiment, association, much of that which is aesthetic in literature; the

prepositions and other intermediaries seek to satisfy the demands of the

intellect for clear and unambiguous

statement. The excellence of Saxon as

a field of study is greatly enhanced by the circumstance that two eras live on side by side in that

language : the one in the old poetry,

which is almost entirely flexional ; the other mixed of flexion and phrase, in the prose

and later poetry.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd E6042) (tudalen 034)

|

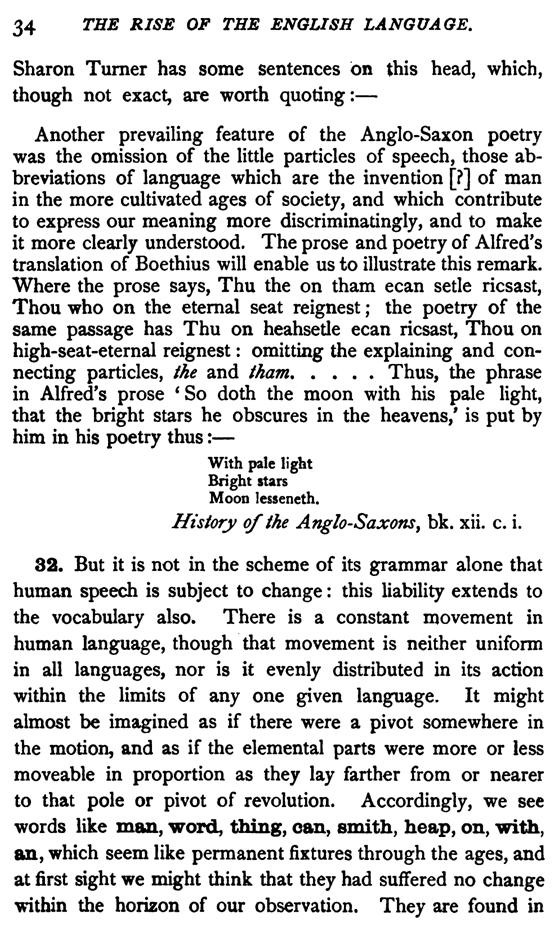

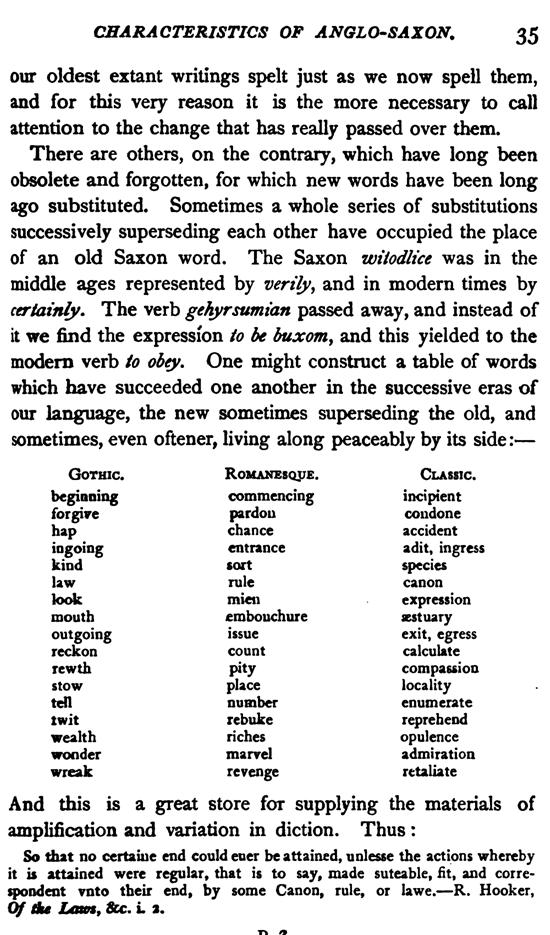

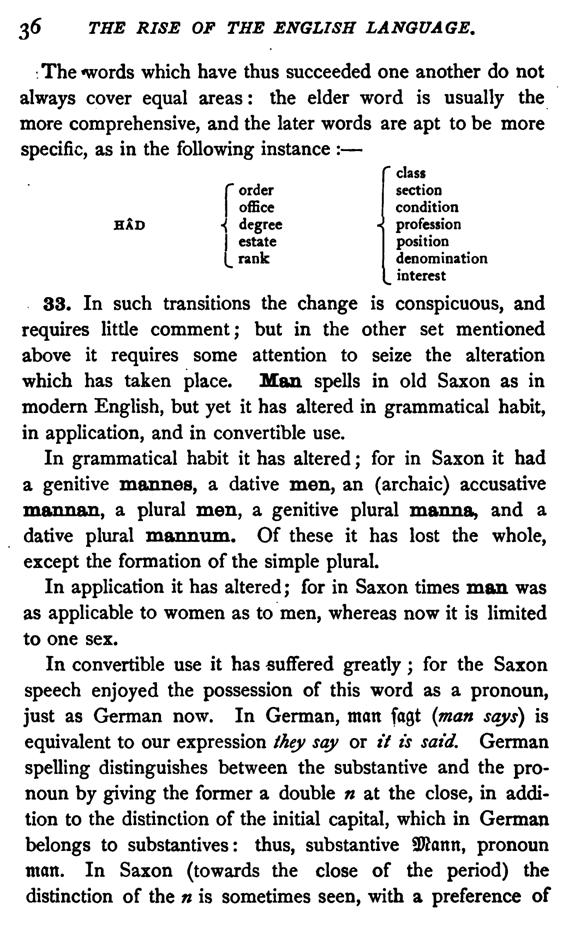

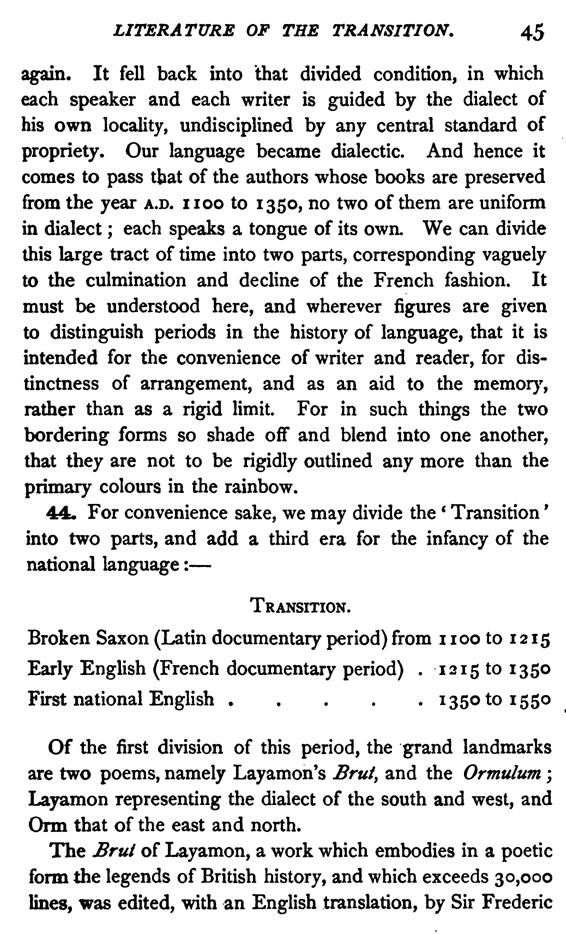

34 THE