.....

|

|

|

|

|

CHAPTER V.

DISCUSSION IN "WESTERN MAIL" — GEORGE BORROW — ROYAL EDUCATION

COMMISSION, 1887, AND NOTES ON THE EVIDENCE OF WELSH WITNESSES — DEATH OF D.

I. DAVIES — CYMMRODORION MEETING IN LONDON, AND THE PAPER OF INSPECTOR

EDWARDS — REPORT OF COMMISSIONERS AND CONCESSIONS TO WALES — ADDRESS OP

PRINCIPAL EDWARDS — PRACTICAL EXPERIENCE IN TEACHING WELSH.

In the previous Chapter I omitted to state that the publication of the

foregoing letters, in the Baner ac

Amserau Cymru, preceded in point of time the formation of the Society for

Utilizing the Welsh Language in education, of which the first general meeting

was held at Cardiff in the autumn of 1885. For a summary of its avowed

objects and principles, see Appendix G. It almost immediately received a very

encouraging measure of support from Welshmen, in almost all parts of

Welsh-Wales, and aroused a spirit of discussion in part ventilated in the

columns of the Western Mail, which,

as we have already seen, opposed its aims.

The Vicar of Ruabon, in a communication to the same paper, ably replied to a

correspondent who had urged the superior claims of French and German on Welsh

children. He says —

The proposal, as I understood it, was to introduce Welsh, not as a substitute

for English, but as an optional specific subject, and to say that a

smattering of French or German that could be acquired at an Elementary School

would be preferable for Welsh-speaking children to an accurate grammatical

knowledge of their own language would seem too absurd. It would probably be

generally admitted that accuracy and observation are the two most important

things to be aimed at in all mental training. And, regarded simply

|

|

|

|

|

|

162 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

as an educational instrument, what could there be for Welsh children that

would be more likely to conduce to the formation and strengthening of these

habits than their proper and systematic training in the grammatical laws and

construction of the grand old language in which they think and speak? There

can be no doubt a knowledge of the two languages adds very much to the

intelligence of the Welsh children. But this knowledge taught grammatically,

and, as your correspondent says, philologically, as far as such teaching

could be made suitable for children, would make the advantage they already

possess far greater. Your correspondent was wrong in saying that "every

English or foreign scholar who has mastered the language says that the

literature it contains, does not justify the time and labour of acquiring

it." Mr. George Borrow, quoted in your article of the 18th inst.,

thought differently. The last time I met him, on a pilgrimage to the grave of

Dr. Owain Pugh, at Nantglyn, some 25 years ago, I well remember his saying

that he considered that even the writings of Hugh Morris and Goronwy Owain

alone were quite sufficient to repay anyone for the study of the Welsh

language. This, however, is quite another question to giving Welsh children

the power of reading and writing their own language with accuracy and

intelligence.

Perhaps my readers will pardon my making a short digression, to give some

account of Geo. Borrow, although his book on Wild Wales is doubtless familiar to some of them. His father had

a military appointment in Ireland, where the son learnt some Irish, and

afterwards as a lawyer's clerk in one of the Eastern Counties of England, he

took up the study of Welsh, being assisted by a Welsh groom, whose

acquaintance he had formed.

As he was of Cornish descent on one side, he possessed a certain ingenium which I have no doubt much

facilitated the acquisition of Celtic languages. However that may be, he was

not content with a mere smattering of Welsh, but acquired a sufficiently

extensive knowledge of it, to read almost anything

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V. [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 163

in the bards. How did he attain what many Welshmen themselves fall short of?

By reading Dr. W. O. Pughe's "Coll

Gwynfa" ("Paradise Lost") twice side-by-side with the

original. Many years after he travelled in Spain and Portugal, and gave to

the world the records of his journeys in "The Bible in Spain," but

he never forgot his early love of Welsh; and in 1854 went a walking

expedition through the country. His work is marred by the introduction of a

good deal of public-house chat, but it betrays an acquaintance with Welsh

literature far more extensive than is to be found in the works of

half-informed English tourists of an earlier date, whose works are looked up

to as standards, and in vain we search Pennant and Nicholson, or such County Histories

as Fenton's and Coxe's for the kind of information we get here.

George Borrow did not go to gaze on half effaced effigies in parish meeting

houses, to describe the gables of manor houses, or even so much the beautiful

scenery of the country, as he went to see the people, knowing not merely their language but the character of

their literature; not merely so, but he was able to quote their poets from

the stores of his powerful memory, e.g.,

on the top of Snowdon, he repeats —

Oer yw'r eira ar Eryri, — o ryw

Ar awyr i rewi;

Oer yw'r ia ar riw 'r ri,

A'r Eira oer yw 'Ryri.

O Ri y 'Ryri yw'r oera, — o'r âr

Ar oror wir arwa;

O'r awyr a yr Eira,

O'i ryw i roi rew a'r ia.

and then relates how three or four English stood nigh with "grinning

scorn," and how he apostrophized a Welshman who came forward and shook

his hand. "I am not a Llydawan

|

|

|

|

|

|

164 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

[a Breton]. I wish I was, or anything but what I am, one of a nation amongst

whom any knowledge save what relates to money-making and over-reaching is

looked upon as a disgrace. I am ashamed to say that I am an Englishman.

Despite its blemishes Borrow's Wild

Wales still remains the only book in the whole circle of English

literature which illustrates fairly-well the literary side of the Welsh

character, though he almost entirely omits mention of nineteenth century

writers, nor can an introduction to this period suitable for English students

be found anywhere at present.

Matthew Arnold a few years later called the attention of the English public

to Welsh literature, but as he was unacquainted with the language he was

naturally unable to take a comprehensive view of it.

I will now select another letter from a well known Welshman, which is

valuable, because it is an unvarnished testimony to the result of these

parents' prejudices, which, unhappily, appear to be given way to, if not

fostered by some elementary teachers, if not school managers. Newspaper

correspondence, as a rule, is not worth reproducing, but I cannot debar

myself from using it on the present occasion, because it illustrates (1) the

intellectual and social history of Wales, in a certain part of the nineteenth

century, (2) the action of general principles, and is of assistance in

forming conclusions, which the mere ipse

dixit of the author would not warrant.

E. Roberts, of Pontypridd, wrote as follows: —

My good father, holding then the mistaken notion held by some still, that a

knowledge of Welsh would retard my progress in learning English, forbade me

to have anything to do with the Welsh language, and even went the length of

forbidding me to attend a Welsh Sunday School. Submitting to the parental

authority, I did not attend a Sunday School or attempt to learn Welsh until I

was about sixteen years of age, although

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V. [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 165

I was practically a monoglot Welsh lad. My education up to that period, I can

assure you, was anything but a pleasure, for the little I learnt was learnt

mechanically; the intellect had nothing to do with it. When I thought of

entering college I thought it high time that I should know something of what

grammar really was. I therefore procured Mr. R. Davies's Welsh Grammar, and

committed a great part of it to memory; but, this grammar being so erroneous

in many parts, I had but an indistinct

idea of what grammar really was, until I

began to translate from Latin into English. Then my eyes were opened

on the subject, and all that I had stored in my memory first became of any

use to me. But what a drudgery I had passed through previous to this! And

that simply because the familiar Welsh was not used as a medium for

explaining matters to me. I have thus given my experiences at some length,

because my own case is an illustration of the difficulty which a Welsh boy

meets with in trying to learn

English without the aid of his native tongue. It is my firm belief that if

what this Society aims at doing had been done in my youthful days, I would

have made a great deal more progress

intellectually and educationally, in English and in Welsh, than I

did. The sad experience of my youthful days makes me yearn for some method of

teaching Welsh boys similarly circumstanced in a more intelligent and

pleasurable way.

As a set off against this may be mentioned the opposing attitude to the

movement, which was taken by Professor Vance Smith of Carmarthen Presbyterian

College, although only a recent settler in the country, and ignorant of the

language. He met an able antagonist in Beriah G. Evans, the master of the

Llangadock Village School, but since attached to the staff of the South Wales Daily News. It is really

surprising that a person who must have possessed some educational

acquirements of an advanced character should have allowed his mind to be

blinded by prejudice, as to oppose the removal of an antiquated and effete

system of education

|

|

|

|

|

|

166 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] CHAP.

V.]

replete with both social and intellectual disadvantages, but which still more

or less leavens nearly all the educational institutions of Wales. "The

artificial propping up of the Welsh language" was a phrase used by Vance

Smith, which a real thinker sliould have scrupled to use. What is artificial,

is to purposely neglect the ordinary medium of thought, for the expression of

ideas until a sufficiently secure foundation for their reception has been

obtained through the use of another medium.

I quote the following from B. Gr. Evans's reply: — You will, I am sure,

readily concede that, being yourself only a recent coiner to Wales, you

cannot be expected to understand Welsh, questions so thoroughly as those who

have spent their lifetime among the people do. More than this, not being

yourself possessed of the key of the Welsh language, wherewith you might be

enabled to open for your students the door to further knowledge, you are

placed under a serious disadvantage for estimating its practical value as an

educational medium. Were the objects of the Society is to cultivate Welsh at

the expense of English, then there would be force in your reasoning.

'■' * I would appeal to you, sir, to throw the great, influence your

position as principal of so important a training institution in Wales gives

you to promote and not to obstruct a movement calculated to remove such

disabilities, and which has already secured the adhesion of leading

educationahsts who have enjoyed a hfe-long practical acquaintance with the

people, their language, and their needs.

In 1886, a Royal Commission was appointed to enquire into the working of the

Education Acts, of which the late Henry Richard was a member. The subject of

bilingualism would probably, as usual, have been ignored had not that veteran

champion of Wales secured its insertion in the syllabus of the points of

enquiry. As a consqeuence, various Welshmen interested in the subject, were

asked to give evidence.* In the course of their examination it was clearly

indicated that room

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 167

was open for the Government to make very considerable modification of these

regulations as applied to Welsh schools. In fact, scarcely anything but a

Code devised specially for Wales would have sufficed to remove all the

legitimate objections raised of the present course of Welsh Education.

The names of the witnesses who gave evidence on the bilingual question were

Ebenezer Morris, of Menai Bridge, Beriah G. Evans, Dan Isaac Davies, B.Sc,

Dr. Isambard Owen, M.A., D. Lewis (Rector of Merthyr), Archdeacon Griffiths,

T. Marchant Williams, Prof. H. Jones, of Bangor, and W. Williams, M.A. (Chief

Welsh Inspector of Schools).

The evidence of these witnesses contains opinions or facts nearly identical

with some which are noticed elsewhere in this book; but at the risk of being

thought guilty of repeating myself, I venture to give a digest of some of its

more salient features, which I believe will not be uninteresting to future

students of Welsh history, whether they be so now or not.

Among the disadvantages arising from the present# system of ignoring Welsh,

it was stated that—

It makes a child nervous and afraid to give expression to his thoughts.

Either he hates the language of his home or hates the foreign language. Evans.

Injury done is permanent. Majority leave school without literary knowledge of

either language. Do.

Contributions to the Welsh press of a low order, through inefficient

instruction, tend to debase the native purity of the language. Do.

If a teacher followed a well-defined system he would have no credit given him

in the report. Do.

* The evidence has been re-published from the Blue Book in a collected form, under the title of Bilingual Teaching in Welsh Elementary

Schools. Price 1s. J. E Southall, Newport, Mon.

# I say at present, because nearly

all these difficulties remain, while only a few schools teach Welsh.

|

|

|

|

|

|

168 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] CHAP. V.]

Does not give the language the status of honour and respect it should occupy

in the child's mind. Evans.

"The Welsh Sunday School is over-weighted, and has not only to teach

religion" but also reading. D. I.

Davies.

Parents in ignorance. Fancy a man cannot have two mother-tongues. Contradicts

this from experience of his own family. Do.

Reason why, "gentry of Wales " do not command the influence they

ordinarily might, is that they give up the language before the people. Do.

Omission of Welsh from pupil teachers' examinations a serious practical

grievance. English girl from Cardiff to Bristol with a smattering of French

gets marks for it. A Welsh girl who knows her own language far more

thoroughly, gets no marks, and is shut out of her own college. Do.

Had it not been for the Welsh "Sunday” school, very little real work

would have been solidly done by our English schools. Griffiths.

Experience as Inspector of Schools in London, and as a teacher is, that

neither German or French can be taught satisfactorily in a public elementary

school under existing circumstances for many years. M. Williams.

Children often puzzled by anomalies in English Grammar, it would be a great

advantage if Welsh grammar were taught.

Do.

If it were taught it would remove the shyness of Welshmen, and improve them

intellectually. Do.

Many teachers think teaching Welsh would involve a great deal of additional labour

* * I say, however, the teaching

of Welsh systematically would be helpful to them in every sense. Do.

Good of Wales dependent to a considerable extent on meeting the difficulty —

no community ever improved except

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 169

by developing the forces, intellectual and otherwise, that it possesses, and

Wales will never be made richer by neglecting its language; nor do I think

the English will be known better. For on the border counties where they do

leave their Welsh, or have done so, and become English, there is a

degradation of intelligence, because they do not really become English.

Prof. H. Jones.

Speaking of parents — the majority, especially the more intelligent, would

see the importance of teaching Welsh.

Do.

[re Candidates for Training College]. The Welsh are very much handicapped by

having to be examined in a language which is not their vernacular. Chief

Inspector Williams.

Believes English might be more thoroughly acquired by the use of Welsh. Do.

Teaching Welsh as a special and class subject may prove a great blessing to

the children. Has not quite made up his mind on the subject. Would like those

who believe in it have a chance to try. E. Morris.

"They only learn to read like parrots." Do.

Thinks poetry should not be included in English. [Why could he not say, he

would substitute Welsh poetry?] Do.

Take number of chapels of four leading denominations, as 3511; of these 2853

are entirely Welsh, 898 English. Evans.

English chapels as a rule small, and ill-attended. Welsh services often

crowded. Do.

"Sunday" school the great educating medium for the Welsh-speaking

population here, they have obtained the only instruction in their own

language they have ever had. Do.

Welsh literature made accessible to them by "Sunday" teachers. Do

|

|

|

|

|

|

170 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

Wide-spread taste among working classes for Welsh literature and composition;

but absence of educational facilities to attain a grammatical knowledge of language. Do.

Better enunciation in reading found

in Welsh schools than in Gloucestershire. Davies.

Took a bilingual parish in Brecknockshire; found people could not read Welsh,

but anxious to have sermons in it. They have a fondness for the language — it

is the language of their inner soul, so to speak. Lewis.

Neath very much Anglicized, people do their shopping in English, but the

people will go perhaps in scores to an English chapel, but by hundreds to a

Welsh one. No predecessor of his [at Neath] could preach in Welsh with

anything like fluency for 50 years. Griffiths.

Englishmen as colliers — "before they have been underground six months

they come out as Welshmen." Do.

National virtues found to a greater extent in Llanelly than in more

Anglicized Swansea. Do.

Circulation of 100,000 (Welsh) newspapers every week: 60 years ago not one. Do.

The additional time and labour involved in carrying out our suggestions would

be trifling indeed. Williams.

Modern Welsh poets frequently have more power than they are able to manifest.

Jones.

Welsh treatise on the philosophy of Hegel, another text book on Logic

commended. Conducted lectures in Welsh on Greek philosophy and on modern

ethics at Bangor; and "more admirable classes," chiefly of working

men, he never had. Did not know "any cultivated Welsh person" who

did not prefer to attend worship in the Welsh rather than in the English

language. Do.

Archdeacon Griffiths introduced into his evidence the utterances of an

eminent Welsh scholar, Robert Williams,

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. l7l

a Vice-President of Lampeter, and of Bp. Thirlwall, which I have reserved

till last, so as not to break the continuity of the summary. These

authorities are quoted in the evidence (abridged) as under: —

"I have often known people whose reading language was English, but whose

speaking language was almost exclusively Welsh. What a confused medley of

words and things must thus be produced in their minds. How the eye of the

intellect must be dimmed, and its edge blunted, by the half caught gleams of

ideas and tangled mass of doubts thus presented, which it can neither see

distinctly nor decide with certainty. Can this be called education? or is it

giving the mind of our peasantry fair play?" Then another short passage

that I will read is this: "But what if, by our neglect of Welsh, we are

throwing away a great gift of Providence? Is there any reason why a people

should not learn and thoroughly understand a neighbouring language, without

immediately smothering their own?” Bishop Thirlwall held similar views and

contended that no Welsh child ought to be thrown entirely upon the

contingency that he may by the force of other circumstances than those of school

life acquire sufficient English to cultivate his mind by the means which that

language supplies, and that he ought not to be debarred in the meantime [by

want of elementary education] from the benefits that may be derived from

books in Welsh. He goes on to say. * * "I am fully convinced that no

maxims opposed to these will bear the test of experience; and I rejoice to

find that they begin to be more generally appreciated, and seem likely to

exercise a greater influence on the system of popular education, than they

have hitherto done.”

Six or seven weeks after this evidence was given, the earthly hopes of a

chief leader of the movement were shattered, a severe cold contracted in

London never left him, and Dan Isaac Davies expired 5 mo. (May) 28, 1887.

Very seldom indeed in the history of Wales has any individual risen so

quickly from comparative obscurity to a

|

|

|

|

|

|

172 WALES AND [CHAP. V.

position of such prominent note, and seldom has there been seen a funeral

which manifested so much wide-spread feeling, as well as sympathy with the

national aspirations which he represented. To an outsider, Cardiff may appear

to differ but little from Hull and Sunderland; to such an one the loss of an

educationalist, however great he may be in his own peculiar sphere, would

scarcely be regarded as anything like a public event.

On this occasion between two and three thousand people were gathered from

Swansea, Merthyr, the Rhondda Valley and other places, forming a procession a

mile in length. I will not here introduce any reports of the speeches

delivered on the occasion by various well-known Welshmen, some in Welsh and

some in English. But enough has been said to shew that there was an

indication of a remarkable amount of national feeling which would scarcely

have been expected, and I think it convincingly shewed that the principles he

represented were not simply the property of a few agitators or enthusiasts,

but very largely echoed by all classes in Wales — South Wales at least.

I venture, however, to give a short extract from "Morien" on the

event, which, although Morienic in its style, comes from the pen of a ready

writer —

In the scholastic circles of the Principality he had been long known and

admired; but at the time of his death, his name was rapidly becoming a

household one in the homes of his fellow-countrymen generally. His mind was

not too much imbued with "awen" to forget the practical in the

imaginative. WhUe others simply cried, " Oes y hyd i'r iaiih

Gymrafg." Mr. Dan Isaac Davies worked in the path of progress, and he

fell, to rise no more, whilst engaged in re-opening the national avenues of

the native language of the Welsh people. We had hoped that Wales had, at

last, found in him one sufficiently able and earnest to restore the Cymric

tongue to its ancient dignity as one of the learned languages of Europe, by

making it the channel by which the youth of Wales

|

|

|

|

|

|

[CHAP. V. [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 173

might reach quickly the vast treasures of knowledge contained to-day in the

English tongue. It is perfectly true that Mr. Davies had two objects in view

by his propaganda, namely, making use of the native language of the Welsh in

the work of education, and thereby facilitating the progress of Welsh

children in the paths of education, and also restoring its lost dignity among

scholars, of the great language of the Cambro-British people. * * Poor Dan

Isaac Davies! With tears we lament thy death; thy work is done, for,

doubtless, thou wert, in the mysterious ways of Providence, only to

inaugurate a movement which will be long associated with thy name. Thou wert

only to utter the old cry, "I'r lan

a'r gain faner goch!" Thy early death seems to sanctify the

movement! "Gorphwys, frawd, mewn

tangnefedd."

In 1887, Welsh education came very prominently before the Eisteddfod meeting

of the Cymmrodorion, held in London, and in the course of one of the meetings

a paper was read by W. Edwards, M.A., Government Inspector of Schools,

Merthyr Tydfil district, which I venture to insert here nearly entire.

As a whole, it is far too good a production to be consigned to the oblivion

of fugitive literature, such as is the fate of the large majority of papers

read at congresses and meetings of various kinds, except those perhaps of a

purely learned character, which mark stepping stones in the progress of any

particular art or branch of science.

Perhaps I shall be found fault with for taking up so much space with matter

which is not original. If so, I would say that one of the objects of this

book is not to present any one man's opinions or views on subjects which so

closely concern the educational future of Wales, but to collate expressions

from witnesses of very different antecedents, education, and circumstances, so that from

the whole a better judgment may be formed of the facts of the past, and of

the requirements of the future. Indeed there is a need for it. Much has been

said

|

|

|

|

|

|

174 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] CHAP. V.]

and written, and yet the subject is so far from being thrashed out that, it

is still one on which a definite verdict is yet to come.

From the point of view of a Government Inspector we scarcely expect

enthusiasm, but we have here something more necessary, viz., impartiality and

penetration. In reading it, one can only feel regret that at present the

enlightened standpoint of the author is far in advance of that of many

managers of schools, and of many Welsh teachers. He says —

As one of the Inspectors charged with the administration of the Education

Act, I beg to state that I regard the question of the utilization of Welsh

purely as an educational one. It has no necessary relation to party or to

sect. Nor do I appear here to join in any appeal for alteration in the

present Code, which is probably elastic enough to admit of any change of

practice that may be desired by the Society. What is really required now is a

discussion on the principle, and in a matter of so much importance no one

should stand aloof who can help the public to understand the principle and

the reason why it is advocated. It is with many an incontrovertible axiom

that the Welsh language is the bane of Wales, and that every friend should

aim at its extinction. Others admit that a language spoken by only a

thirtieth part of the population of these islands must essentially be a

disadvantage, through the limitations of intercourse which it imposes, even

although it were the most ancient and perfect language known to history. Let

it be conceded, not absolutely, but for the sake of argument, that it would

be beneficial for Wales if the native language were totally supplanted by

English, the question remains as to the best means of arriving at this

consummation. Now, there can be no doubt that the exclusion of Welsh from all

the elementary schools, from all the grammar schools, and from all the colleges,

is damaging to the vitality of the language. It operates in two ways: (1)

directly by subtracting so many hours every day from the time that would

otherwise have been spent in the practice of the native tongue; (2) by giving

the Welsh a low-caste character.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 175

Welsh suffers in prestige from being totally ignored, when other subjects are

honoured, and a tendency will be formed in the case, at any rate, of some

children to speak bad English in preference to good Welsh. I cannot,

therefore, deny that the cumulative effects of what I may call the repressive

system, acting through many ages, will eventually destroy the Welsh language,

especially in combination with many other outside influences; such are set up

by the social and commercial intercourse with England, and the immensely

preponderating quantity of English literature.

But when this is agreed, how much time must be allowed for the completion of

the process? It is dangerous to prophesy, but I do not fear to affirm that

more than a hundred, perhaps two hundred, perhaps 500 years will be required to

achieve the death of Welsh. For it must be remembered that a repressive

policy, in order to gain its end with any degree of rapidity, must also be

complete. It is not enough to exclude Welsh from the schools and colleges. You

must also make it penal to speak Welsh at fairs and markets, to print Welsh

newspapers and books, to preach Welsh sermons. If you cannot or dare not do

this, the language will resist for centuries the effect of its banishment

from education.

It is a plausible assertion that children who hear and speak and read only

English at school, will become really familiar with that language, and

discard the vernacular for the rest of their lives. But no account is here

taken of the Welsh environment. Even while the child is attending school the

outside intercourse counter-balances to a considerable extent the effect of

school atmostphere. Nay at the school itself, during the time of recreation

Welsh is the language of play, as I have had many opportunities of observing

in my own district, which is far from the centre of Wales. It may be doubted

whether the child is subjected to English influence for more than five hours

in the day. He is probably more than double this time under the influence of

purely Welsh surroundings. When his school career ends, at the early age of

twelve or thirteen, the environment is wholly Welsh, and it is not merely

antecedently probable, but a matter of experience that in parts of

Cardiganshire,

|

|

|

|

|

|

176 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE} CHAP. V.]

Merionethshire, and even of Glamorganshire, away from the towns, the child

frequently in a few months loses almost all his hold of English. Although

therefore it may be admitted that the day schools do exercise a decidedly

inimical effect upon the life of the Welsh language, it should at the same

time be remembered that their influence operates only during the third part

of the child's working day, and ceases altogether at a very early age.

If the schools were all boarding schools, so that the children might be

withdrawn from all contact with the Welsh stock from which they sprang, the

effect might conceivably be more measurable, hut even on this hypothesis the

Anglicizing influence would be incomplete, unless the children were confined

to separate cells when not under instruction. The people who are sanguine of

the speedy success of the present system do not realize the difficulty of

killing a language, which at the present moment is very far from moribund,

and may live as long as Dutch or Danish. The total neglect of Welsh will

surely help to sap the vigour of the language, but what happens during the

long era which must elapse before the end comes? A policy which gags the

mouth of a child, stupidly ignores the habits and associations of home, and

crushes every native sensibility, can only result in immense waste of energy,

in the lowering of the tone of the nation, and in a paralysis of the

intelligence of many generations of Welshmen. Is it fair that even a

barbarous dialect should be so ignored in education as Welsh is at present?

There is an outcry of sympathy if the children of Lapps and Poles are treated

in this way, but nearer home there is a case of outrage upon nature and

reason which is worthy of equal condemnation.

The blame rests upon the Welsh themselves for the continuance of this state

of things, for the Department has not yet refused to grant any concession

which has been asked for by the Society.

* * Words may be read to almost an unlimited extent without the

assimilation by the mind of the ideas to which they correspond. By the

bilingual method the link between the English word and

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 177

the idea is established. In the study of any other foreign language this is

the method that would universally be adopted.

It has been urged that the best way to teach a child Prench is to send him to

school in France, where he would hear no English. But the cases are not

parallel. In one case the whole environment would be French, and the child

must learn French, as a child is sometimes taught to swim, by being thrown

into deep sea. You have not the struggle between the environment and the

school, which creates the chief obstacle in Wales.

The advocates of bilingual teaching recommend that in districts where Welsh

retains its hold as the common medium of intercourse, Welsh and English

should be taught in connection. Welsh as well as English reading books should

be used, the one set being idiomatic translations of the other. These books

are not merely an instrument of interpretation, but also subject matter for a

comparison of the grammar and idioms of the two languages. In some districts

Welsh is weak, or divides the field equally with English. There, Welsh would

be more advantageously taught as a specific subject to the highest standards

for its purely educational value, while in the lower standards Welsh might

occasionally be employed for purposes of illustration. In every town or

village where any Welsh is spoken an opportunity should be afforded of

learning to read and write Welsh correctly at some period of the school

course. It is not proposed by the Society to agitate for the compulsory

reading of Welsh, as it is feared by some. They wish to make the teaching

simply permissive. There are many prejudices to be overcome on the part of

school managers and teachers and parents before the movement in favour of

bilingual teaching becomes general.

There are some persons, be it observed, who make it a reproach that Welsh is

so seldom spoken correctly by the masses. Should it not rather be a matter of

wonder* that the idiom is so purely maintained when the only instruction in

Welsh is given in Sunday schools? But the same individuals inconsistently

oppose the only

* How true this is, those who know Wales can vouch.

|

|

|

|

|

|

178 WALES AND [CHAP. V

means by which the defects in the common speech can be cured.

As a matter of fact, the language of a Welsh peasant is far more correct than

that of his compeers in England. The Marquis of Bute said at the Cardiff

Eisteddfod, "For a man to speak Welsh, and willingly not to be able to

read or write it, is to confess himself a boor." This is a noble sentiment;

and it should put to shame those others who wish to keep down the Welsh as a

nation of boors, rather than grant the instruction which would save them from

the reproach. The bilingual idea is to be applied to schools of all grades.

Eor there should be no division of classes.

What has done so much mischief in Wales in times past and present is the

chasm existing between the English-speaking landowner and gentry and the

Welsh-speaking community. What separation of interests, material and

spiritual, has resulted from this cause!

Let the opportunity, at all events, be given to the children of all classes

to learn the rudiments of the language of the people. To a very numerous

class, viz., to those who are to become the ministers, the lawyers, the

doctors, and the teachers of Wales, instruction in Welsh will clearly be a

professional advantage.

One strongly felt objection to the proposed Welsh-English instruction is that

although the object primarily is merely to utilize Welsh to learn Enghsh

better than to improve the general intelligence thereby, yet Welsh itself

will at the same time be improved. This is to some people a great rock of

offence. They are afraid that the longevity of Welsh will be favourably

affected when it is systematically taught, even in a parallel line with

Enghsh. Even if their fears are well founded, the objection cannot be

listened to, if it is true that only by biUngual instruction can a Welsh

child have an intelligent grasp of English. But I feel certain that the life

of Welsh will not be appreciably prolonged by its recognition in schools. The

status of the language will be raised, a more correct way of speaking will be

in vogue, but it is the very essence of biUngual teaching that it makes the

scholar facile in two

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. l79

languages. If Welsh will be strengthened, English will receive an accession

of vigour.

Tou may have a bilingual nation for any length of time, if by bihngual nation

is meant a nation, two sections of which speak different languages, but there

is no instance on record of a nation of bilinguals. Switzerland is no

example, for the bihngualism of Switzerland is only the overlapping of the

French and G-erman, and such a bilingualism is obUgatory along every border.

But when every Welshman knows English as well as he knows Welsh, and there is

no nucleus of monoglots to act as a preservative, the weaker language vdU

then rapidly die. But it will die a honourable death, instead of being

strangled in disgrace. Welsh will have done its work. The continuity of the

nation will have been preserved. The parents and the children will not have

been made strangers by the premature forcing of an alien language. The

children of the EngUsh resident will be brought into kindlier intimacy with

the children of the Cymry. Finally, time will have been given for the

transference of whatever is worthy in Welsh literature to the kindly keeping

of that universal inheritor, the language of England, in which the genius of

the Welsh will find a larger and more durable home.

What do you say, my readers, to having these lines written in gold on the

portals of every school and every college in Wales.

Zbe bilingual idea is to be applied to scbools ot all grades,

What say you to ousting, as ignorant or incapable, every school manager, be

he a high and mighty cleric or a village grocer, vrho will not subscribe to

this advice of the Inspector — " In every town or village where any

Welsh is spoken an opportunity should be oifered of learning to read and

write Welsh correctly at some period of the school course."

"Every town or village," recollect, includes those partially

populated by Somerset and Gloucester workmen, the presence

|

|

|

|

|

|

180 WALES AND [CHAP. V.

of whose children is supposed by some teachers to place an obstacle in the

development of the bilingual idea. Why should the children of the soil for

the supposed interests of these strangers be deprived of such opportunities

of reading and writing their mother-tongue as systematic instruction in it

can afford them.

What are you going to do to help fill up this social "chasm" that

the Inspector speaks of (the very expression which was running in the

writer's mind many months ago), caused by a portion of the people by habit,

association, and preference, speaking a language and reading a literature of

which the wealthy and influential are almost entirely ignorant? What are you

going to do to remove those prejudices of school managers, teachers, and

parents, which the same experienced authority tells us must be overcome

before the movement becomes general?

One of the objects of the volume is to call the attention of the Welsh people

to these inconsistencies, and blots upon their character as a practical people,

to the errors made venerable by the incrustations of centuries, to the need

of greater educational enlightenment, and to the desirability (I would here

even go further than Inspector Edwards), of not leaving the decision of these

matters, mainly in the hands of either managers, teachers, or parents, who

are frequently either from inexperience or ignorance, not the fittest

authorities to decide upon them.

Bear in mind, too, that the foregoing paper is not the product of the brain

of an impractical enthusiast, a mere theorist, as some of the opposers of

bilingualism in Wales are apt to class its advocates; it is the expression of

man who is pre-eminently entitled to a hearing though we may differ from him

on minor points. For instance, he appears to the writer to much under-rate

the influence of bilingual instruction in prolonging the life of the

language, but on the central point viz.,

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 181

the desirability of bilingualism, or teaching Welsh, not simply allowing its

use in explanatory processes becoming universal where the language is spoken,

and that it should be applied to schools of all classes, we agree.

If this had been done ten or fifteen years ago, we probably should not have

had the pitiable spectacle, alluded to elsewhere, of a well-to-do Welsh

publisher in Wales unable to read the books issuing from his own press, and

having to depend on the judgment of others as to their character, if he form

one.

In some other points also I am incUned to differ from the author, as for

mstance where he advocates Welsh and English reading books being the

idiomatic translation of each other. To give an effective bilingual

education, this should only be partially the case; some pieces, particularly

poetry, should be inserted in each language and untranslated.

Second only in importance to the Inspector's paper was a short speech by the

then Warden of Llandovery College, in which he said that education in Wales

should be of a distinct, and national, and Welsh character: education was not

merely putting a number of facts and figures into the pupil's head, but

consisted also in the development of the mind: it was not creating, but

fashioning and forming raw material; it was impossible to educate a

Welsh-speaking Welshman unless a knowledge of the Welsh language were taken

into account: although from one point of view it might be a mistake to devote

two hours a week to teaching a boy Welsh, yet it would be found as a fact

that he learnt Latin and French all the quicker for having that knowledge.

Observe that the warden used these adjectives in characterizing what

education in Wales should be.

Distinct. National. Welsh.

Distinct means that there should be a clear essential

|

|

|

|

|

|

182 WALES AND [OHAP. V.

distinction between education in Wales and that over the border, which there

is not at present.

National means that it should be general throughout the country.

Welsh means that instruction in the Welsh language should form an integral

part of such distinct and national education.

These two advocates of biKngualism may be regarded as representative men,

both filling important educational positions, both having a claim on the

confidence of their countrymen.

Take another practical witness — Owen Owen, head master of Oswestry High

School in the Welsh portion of Shropshire. He was strongly in favour of

leaving education in Wales entirely to Welsh men and Welsh women. They should

aim at a "complete and thorough national system," leading step by

step from the village school to the University. I suppose that he also would

be considered both successful and practical in his profession.

In 1888 the Report of the Education Commissioners was issued, which shewed

that although it was composed entirely of Englishmen, with the single

exception of Henry Richard, they had been so thoroughly convinced of the

reasonableness of the demands of the Utilization Society, that almost every

point asked for was conceded to. They recommended —

That schools in Welsh districts should be allowed to teach reading and

writing of Welsh concurrently with English.

Permission to use bilingual reading-books.

Liberty to teach Welsh as a specific subject.

To adopt an optional scheme for English as a class subject, founded on the

principle of a graduated system of translation from Welsh into Enghsh for the

present acquirement of English grammar.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 183

To teach Welsh with English as a class subject.

To include Welsh among the languages in which Queen's scholarships and

certificates of merit may be annexed. The next step to which the friends of

the movement turned their attention was to secure the adhesion of the

Government to these recommendations, so that it might be possible to give

them practical effect. In this work Sir John Puleston, M.P., himself of a

North Wales family noted in these pages, took an active share, and repeatedly

interviewed Sir W. Hart Dyke, the President of the Committee of Council on

Education.

The result, as is well known, was regarded as a complete success for the

principles of the Society; every recommendation of the Royal Commission being

adopted by the Government, with the exception of the inclusion of Welsh in

Queen's scholarship subjects for pupil teachers. This was a great omission,

but it is hoped that it may be remedied before long. As one of the South

Wales papers pointed out, these concessions in effect, open the door for a

thorough change in the whole system of Welsh elementary education, although

little prominence indeed is actually given them in the Code; but besides

embracing the afore-mentioned recommendations, in practice they give

advantages not quite apparent to one not familiar with elementary school

working, which are indicated by the following summary.

I. A grant of 4s. to be paid per head for each child passing in Welsh

Grammar, as a specific in Standards V., VI. and VII.

II. A grant of 2s. per child in the average of the whole school for

successful results in teaching English as a class subject by means of

translation from Welsh to English.

III. In all standards, and in all subjects, bilingual reading-books may be

used, and bilingual copybooks may be used in teaching writing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

184 WALES AND [CHAP. V.

IV. The geography of Wales may be taught up to Standard III., and the history

of Wales may be taught throughout the whole school, by means of books partly

Welsh and partly English, and a grant of 2s. per head on the average of the

whole school may be earned for each of these subjects if the results of the

examination are satisfactory.

V. Schools taking up the new method of teaching English as a class subject

may also claim the right to substitute translation from Welsh to English for

English composition in the elementary subjects, and thus reap a double

benefit.

VI. Finally, the small village and country schools, so numerous in the

Principality, may, for the purpose of class teaching re-arrange the standards

into three groups, e.g., Group 1, Standards I., II.; Group 2, Standards III.,

IV.; Group 3, Standards V., VI., VIII. This will be a material relief to

under-staffed schools.

In the Spring of 1889, after these concessions had been made known, a meeting

of the Utilization Society was held at Aberystwith, the Earl of Lisburn

taking the chair at the public meeting. At the previous members' meeting

Principal Edwards in the course of an admirable speech remarked —

It appears to me a real danger to the intellectual and moral life of the

Welsh people, this transition from "Welsh to English. Whatever may be

said about Welsh, it is a simple fact that Welsh is a literary language. It

has been found amply sufficient to express the most abstract truths of ethics

and religion. It is at once the symbol and the instrument of a civilization.

To regard such a language as an encumbrance, and not a most potent ally, in

the education of the people who think and worship in it, whose intellectual

and moral life is fashioned by the ideas it has conveyed to their minds, is

fatuous and guilty conduct. (Cheers.) To permit the people of Wales to lose

their knowledge of literary Welsh, the language of the Welsh Bible, so that

they will under-

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 185

stand no other Welsh than the laongrel patois of the streets, is to abandon

deliberately the creative influences of the past, to break for ever with the

enobling examples of our great men, to throw away the heritage of many

centuries, in order to start afresh forsooth from the low intellectual and

moral condition of savage tribes. Let English come into Wales and take

possession, if it can. But let the intellectual and moral life of the future

be the natural development of the past. This it cannot be if we foolishly and

criminally neglect to teach literary Welsh until we have accomplished the

task of teaching literary English. Hitherto, this most important work has

been done in Wales by Sunday schools. Putting aside for the moment the

spiritual interests of Wales, and regarding the question only in its

intellectual aspects, I do not hesitate to avow my strong conviction that all

sects and parties alike ought to acknowledge their indebtedness to our Welsh

Sunday schools and to their peculiar characteristics, and to make a great

effort to maintain their efficiency. But they cannot adequately meet the

demands of the age. The people must be taught, not only to read the Welsh of

Bishop Morgan, but also the Welsh of Goronwy Owain, and to feel in the very

depth of their being the creative influence of the past that should always be

present, and of the dead that never die.

What do you say, you lethargic officials and managers steeped in the

traditions of Whitehall? What do you say to these words of a man whom Wales

delights to honour? The people must (it is in your hands very largely to make

it a practical MUST) be taught not only to read the Welsh of Bishop Morgan,

but also the Welsh of Goronwy, or if Goronwy is too difficult, that of Islwyn

and Hiraethog.

Time has amply justified the following: —

Having obtained all it asked from Government, the Society must take into

account the sluggishness of a considerable number of school managers, in whom

as in most officials, the vis inertiae is strong. Not indeed that the country

at large can be justly charged

|

|

|

|

|

|

186 WALES AND [CHAP. V.

with apathy. An intelligent observer made the remark that whereas the study

of Irish is but the hobby of a few antiquaries in Dublin, the entire people

of "Wales love their language and wish it to live. At the same time, the

Society will not find that all School Boards have enough foresight to see the

necessity for the immediate and full adoption of the concessions made in the

New Code. Public opinion must be continually formed and maintained on the

question, until the use of "Welsh in teaching English and the teaching

of "Welsh as a literary language become universal in "Welsh

speaking districts. But this will never be brought about unless suitable

text-books are provided. * * A strong and successful Society is an instrument

for good which ought not to be thrust aside too soon, and this Society will

not perish, so long as it adapts itself to the special wants of the time, and

performs its work with the same energy in the future as it has shown in the

past.

Here again we have a man well known outside Wales, whom some of his friends

perchance, think too much of an Anglicizer, often occupying English pulpits,

yet not satisfied with the bare " utilization of Welsh to learn

English," but positively enforcing it as an educational maxim, that the

teaching of Welsh as a literary language should become universal in

jWelsh-speaking districts, and foreseeing that only by continued exertions

can the deleterious whims or caprices of local managers, and the vis inertias

of schoolmasters be overcome.

At the same meeting at Aberystwyth, Morgan Owen, Inspector of Board Schools,

said that he was pleased to see the interest many parents took in the

subject. In South Wales in many cases, though parents objected to see their

children doing home lessons in English subjects, they were very glad to find

a Welsh book brought home in their hands. This apparently conflicts with

other testimony as to parents' views. I conclude that the true solution of

the difficulty is, that in districts where the parents fear that their

children will grow up

|

|

|

|

|

|

OHAP. v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 187

monoglot Welsh, they are often opposed to any secular education in Welsh, but

where there is a danger of the children growing up monoglot English they are

glad of opportunities given at school to return to the old language.

Professor Roberts of Cardiff said —

The great and rapid success of the agitation indicated that the Welsh

language was destined to render another signal service to the nation, in

addition to its services in the past. During the past fifty years, in spite

of the fact that much of the cultured opinion of the country was for

relegating the language into neglect and decay, the body of the people and

their trusted leaders adopted another course. They in fact "

utiUzed" the language — not as a barrier to keep the people in darkness

— but as the sole available means of educating and informing the nation by

speech and in writing. By a flood of lectures and periodicals and other

literature, the people had been so educated that in no part of the kingdom

could the masses be said to be more inteUigent and better informed on all

general questions than in Wales. But while the people thus utiUzed their

language to their great and permanent benefit — it was wholly neglected and

ignored in the official system of education.

Yes, so wholly neglected and ignored that the " flood of [vernacular]

lectures and periodicals" have, in certain districts, become almost

things of the past, though the want of familiarity with the language in the

rising generation, which would have been induced by a Kttle education in it

at school.

T. E. WilUams, Abeiystwith, comparing Radnor with Cardigan, said —

Eadnor had lost its Welsh. By this time it had become EngUsh not only as far

as language was concerned, but the EngHsh spoken in the county was about the

poorest English they could get anywhere, and, educationally, it was one of

the lowest counties, if not the lowest in Wales. On the other hand, let them

take the county

|

|

|

|

|

|

188 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

of Cardigan. There they had Welsh spoken, and, educationally, Cardigan was

one of the highest counties in Wales.

Not merely so, he might have added, but Radnor and Cardigan resemble each

other ethnologically, perhaps, as much as any two counties in Wales, if so,

the inferiority of Radnor is not accounted for by difference of race.

Speaking at the public meeting. Professor Lloyd believed that the study of

Welsh grammar afforded a better mental training than the study of French or

German.

They also wanted to utilize Welsh literature. English literature was no literature

to Welshmen who had grown up to mature years without a knowledge of the

English language. He did not understand the associations — the subtle

associations of the words; and he thought that was well illustrated by the

fact that the one English poet whom Welshmen knew something of and

appreciated was Milton, and the reason was that they understood the

background of Milton.

This may be true, but in fact English literature is "no literature"

to Englishmen who have grown up to mature years, without some previous

literary training in the very language they are supposed to speak. To enjoy

Milton, it is not simply necessary to be born in an Enghsh home, and to have

learnt to read and write.

The literature of the newspaper is accessible, but scarcely that represented by

more modern names, such as Cowper and Tennyson. Welshmen are often

recommended to learn English, or to value it for the sake of the literature;

but in point of fact the best English classics are not much read except by

the professional or leisured classes, and even at this fag-end of the

nineteenth century, perhaps less than ever, if we except co-temporary

writers, whereas a Welshman has less mental labour to go through to appreciate

writers of the same class and degree in his own language, than the Englishman

has in

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 189

his; not that I am placing actual Welsh literature on a level with English,

but shewing its possibilities with regard to the mass of the people.

In the meetings of the Society for the Utilization of the Welsh Language

there has been generally a studious avoidance of praise of the language,

doubtless lest its claim on the public should be prejudiced by the

introduction of sentiment, but on this occasion it was reserved to a

foreigner to Wales, a Roman Catholic Priest (Hayde), of Cardiff, to fill up

the meed of admiration for the intrinsic beauties of the Welsh language. —

Respecting the Welsh language, he might say that he had never studied a

language in which he had felt more interest, more pleasure and more mental

training. The idioms and the structure of the language were so different from

those of other languages that by comparing them the student acquired strength

of mind, and that was the great end of education. ■■' * Welsh was

not only a most beautiful language, but would compare favourably with Itahan,

Spanish, Portuguese, German and others with which he was acquainted; and he

said further that if Welsh had been developed as German had been developed

during the past one hundred years by some of the greatest men who had ever

lived, and as EngUsh had been developed by the writings of Shakespeare and

others. Welsh to-day would have been looked upon as one of the most perfect

languages on the face of the earth.

He ended with a short address in Welsh, quoting —

Tra'r mor yn fur i'r bur hoff bau, O bydded i'r hen iaith barhau.

So much for the utterances of public men and officials. They are neither few

in number nor deficient in sense and quality. Supposing these expressions of

opinion, these marks of sympathy with a proposed public object, had been made

with a corresponding intensity in England, can we suppose for

|

|

|

|

|

|

190 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V,

a moment that the English character would have allowed the whole thing to

sink into partial oblivion?

Certainly not. There would either have been dissentient voices, strongly

biasing public opinion in the other direction, or else those who had put

their hands to the plough would not be satisfied, until with the sweat of

their brow, success had crowned their patient and constant endeavours.

Welsh people are not always made of that sort of mettle. They are not very

fond of facing wind and weather, and of actions as good and as sound as

words. I have spoken of public opinion; although a solution of this question

will affect every family in Welsh Wales, and a great many in English Wales,

it is not to be supposed that it is exactly one in which the mass of the

population have a mature judgment, but it certainly deserves to be met with a

distinctly active attitude, either of opposition or of positive countenance

and co-operation by intelligent persons interested in the conduct of Welsh

education.

So far as opposition goes, few movements spread over a large area have

encountered less of an open and public kind. What then are the tangible

results before us in Wales? After the great exertions made by some friends of

the new Society; after the lapse of six years in the work of practically

reforming the system of elementary education, directly they amount to little

more than the following, viz.: —

1. The publication of two small text books* for teaching Welsh as a

specific subject, while the third advertised some years ago as "in

preparation," is still, so far as the author's information goes, lying

in the limbo of the future.

2. The introduction of Welsh as a specific subject into a few schools,

mostly in semi-Anglicized districts.

* Welsh Stage I., 1887. Welsh Stage II., 1889. Simkin Marshall and Co.,

London; 6d. each.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V,] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 191

It will thus be seen that at the end of six years the great majority of the

rising generation is untouched, and unaffected by this incipient reformation.

This is at first sight discouraging. In reality, however, it is not quite so

much so as may appear, although direct results are extremely meagre.

Indirectly, there is reason to believe that the educational status of Welsh

has been somewhat raised, and a further place assigned to it in developing

the intelligence of children than previously. This cannot be however,

thoroughly and efficiently done without the use of Text Books, partly printed

in Welsh, in the actual course of instruction in elementary subjects.

The Bilingual Books which, in 1889, the Council of the Welsh Utilization

Society was to issue "without delay," are still not forthcoming,

and it is to be feared, notwithstanding the warm and zealous recognition of

the Society's claims on Wales, there will be a danger unless more energetic

and thoroughly systematic action is taken, of relapsing into a quiet and

slavish acquiescence in the status quo.

Thus far, some sort of a soporific has prevented the elementary schoolmasters

uniting, as they should do, and knocking at the door of the Society's Council

Chamber demanding the speedy issue of these Bilingual Books, and it is to be

feared that the apathy of the Department is partly responsible for this.

After receiving the report of the Royal Commissioners, which most clearly

shewed that various injuries were being inflicted on Wales, and a certain

amount of educational power allowed to run waste through the present method

being pursued; after the generous concessions made by the Government to the

claims of Wales, how is English-Welsh, as a class subject, treated in the Code?

Simply allowed a most insignificant place, just barely mentioned in a sort of

note. How is it treated in the Departmental instructions to Inspectors for

1890? Surely

|

|

|

|

|

|

192 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

with all this weight of evidence, the permanent oiBcials at Whitehall would

tell the Inspectors that it was their duty to assist in inaugurating a

radical reform in the education of Wales, not in an authoritative way, but by

suggestions to school managers and teachers, and by recommendations that they

should endeavour, as soon as may be, to equip themselves for a better system

which promises to improve the knowledge of English as well as of Welsh. Did

they thus call attention to the first steps necessary to break up the fallow

ground?

No. Not by a single word. It was as if the said permanent officials, or

whosoever drafts out those instructions to the Inspectors, was desirous of

hushing the whole thing up, and in all probability the chiefs — "My

Lords," had too much to think of, to notice such an apparently trifling

omission.

It would, however, be injustice to Lord Cranbrook and Sir W. Hart Dyke, to

question the sincerity of the interest they have taken in the matter, but we

must come to the conclusion that if all the heads of the Department had

reciprocated these sentiments, it would have been easy to have given such

additional force to the movement that every schoolmaster and every manager in

Welsh Wales would have felt a certain amount of moral suasion to change

tactics.

Beyond vice voce explanations &c., the work done has been entirely

confined to dealing with Welsh as a specific subject, i.e., teaching it as a

foreign language in the three higher Standards only. The uninformed reader

may need to be told that specifics are extra subjects, such as algebra,

agriculture, French, physiology and domestic economy, which are to a

considerable extent at the option of the School Board or managers. Success in

these is paid for by a grant per head from the Government.

It is practically found that specifics can only be attempted in few schools,

and many children leave school before entering

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. V.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 193

Standard V. The Utilization Society was quite aware that much more would be

needed than the introduction of the specific, as they said in their memorial

to the Royal Commission in 1886: "We should however deeply deplore the

restriction of concession to Welsh needs to the introduction of the specific

subject only, as from the nature of the majority of the schools in Wales,

such concession would benefit but comparatively few."

To Gelligaer School Board, bordering on Monmouthshire, belongs the honour of

first introducing Welsh, viz., in 1885, before the issue of either of the

Text Books. Some gleanings of the experience gained there and elsewhere will

doubtless be interesting to the reader.

A Welsh schoolmaster thus commented upon the results of the first examination

in the Gelligaer schools: —

Here we have one School Board alone, without adequate text books, and with a

large admixture of English-speaking children among its pupils, passing over

82 per cent, in the first examination in Welsh as a specific subject, and

adding thereby a sum of twenty-one pounds to the school fund in additional

grants. In one instance 62 per cent, of the children examined spoke English

habitually at home, and yet 92 per cent of these English-speaking children

passed successfully in their first examination in Welsh! One purely English

child — a girl — was reported as having attained the third highest place in

percentage of marks for Welsh exercises.

One of the head masters under the Board evidently regarded the matter

something as a fad, and simply allowed two pupils to stand, but later on came

to see that it might be more useful and profitable than he had anticipated,

and successfully passed a considerable number.

In the report to the Education Department (Blue Book of 1888), Inspector

Edwards, of Merthyr, appears to be quoted as speaking favourably of the text

books of the Society; and

|

|

|

|

|

|

194 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

Inspector Bancroft remarked on the fact that children in the English speaking

parts of Pembrokeshire are often remarkably slow in answering one question in

arithmetic.

The Chief Inspector in issuing the report, refers to the great slowness with

which the teaching of Welsh was spreading, and alludes to parents and

managers' objections, comprising the "popular delusion" spoken of

in Chap. IV. He adds very much to the purpose. "Surely a movement which

aims at improving what cannot now be considered satisfactory ought to have a

fair trial, and to be pushed forward by enlightened educationalists, without

waiting for a demand from the parents, most of whom naturally believe that

the present system must be the best that can be devised."

Of course it ought. I am very glad such a man is in such a position, and has

the good sense and boldness to make the remark. Ask the parents their opinion

about the land laws and the Established Church, or the labour movement, and

they have a right to be listened to, but it is a doctrine that should be most

strongly protested against, that they should dictate a system of education to

persons whose opportunities for forming a broad and liberal judgment are far

more extensive than theirs.

Parents in general have but a limited idea of what education, even such an

education as is possible and suitable for their circumstances in life, means:

they need strong minds to direct: so do many school managers, and this

narrowness of culture is one of the difficulties the Welsh has to contend

against.

Inspector Pryce, of Carmarthenshire, in the same report, appears to

depreciate teaching Welsh, which was entirely excluded as a specific from his

district, but gives no reason except the unpopularity with parents, — not of

the language, but of its introduction into secular education.

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP, v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 195

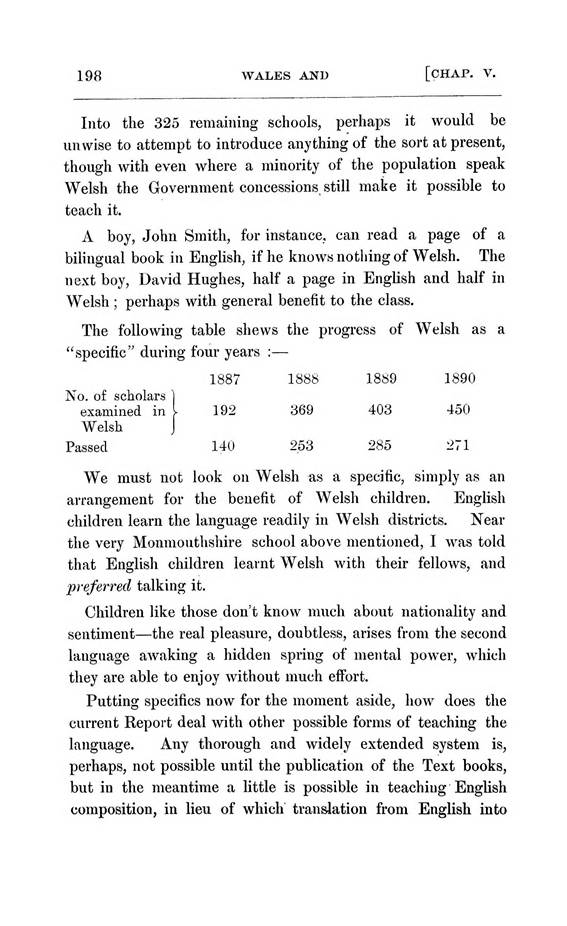

In the Welsh Division Report for 1890, published in 1891, the Chief Inspector

alludes to the fact that "specific subjects are almost confined to

higher-grade Elementary Schools," such as those established in large

towns like Cardiff, where we should naturally expect to find not much Welsh

attempted, and that ordinary schools find sufficient to do without, while

teaching httle more than "elementary, and two class subjects," an

observation which accentuates the remark following, that the "full value

of the movement will not be attained till bilingual reading books be used in

the lower standards"; he even goes further than this, and says that his

experience has strengthened his conviction that advantage would accrue from

using "the child's knowledge of his own language in teaching not only

English but other languages as well."

Although specifics are thus handicapped, after listening to the Chief

Inspector, we will give some consideration to the reports of Inspectors.

The Carmarthen district Inspector says: "Welsh has not yet been chosen

as a specific subject in any school in my district. This is, no doubt, partly

owing to the children in the larger schools possessing a fair knowledge in

English, especially in the higher standards.". Now, in fact, if these

children are bilingual, the reason assigned is a poor one. He admits to

passing 408 in specific subjects; the boys in Algebra and animal physiology,

and the girls in domestic economy. Algebra, it is true, would teach them to

think, but so would Welsh, besides enlarging their powers of expression.

The Denbigh District Inspector says: "Welsh seems to be the popular

specific subject in my district * * * in one school, strange to say, an

English girl beat her Welsh fellows in this subject." This is simply the

Gelligaer experience repeated. If popular in the Denbighshire district, which

includes semi-Anglicized Ruabon, why not in Carmarthenshire,

|

|

|

|

|

|

196 WALES AND [HER LANGUAGE] [CHAP. V.

where a convenient knowledge of both languages co-exists to a large extent?

If the reason assigned is that the children in the latter know Welsh already,

why not, on the same ground, say that they know English already in Llanelly

and Carmarthen, and refuse to teach them English composition.

The Pembroke District Inspector remarks on most of his schools, being unable

to go in for specific subjects, that Welsh would "probably be more

popular as a class subject, as there are but few scholars above the 5th

Standard."

The Merthyr District Inspector (W. Edwards) says: That as things are at

present, Welsh is begun to be taught too late in a child's course, and that a

boy cannot take kindly to the conjugation of Welsh verbs, and the declension

of nouns, when he has not previously read a Welsh book, and become familiar

with the written form of the language, which he only knows colloquially.

What is said from the Carnarvon district, the "very headquarters of

modern Welsh literature, and Welsh writers the classic ground of llenorion a beirdd now, and perhaps for a long period, in the future?

Absolutely nothing. The Inspector has an English name, and though he may

possess a small knowledge of the language, it is believed that he rarely

exercises it.

In bilingual districts the subject is more likely to be popular with parents,

but the ogre of the English manager

or member of a School Board, who thinks he knows what the children want, but

wishes to checkmate Welsh, is still more likely to present itself. Perhaps he

is a colliery or tin-plate manager, or even a tradesman from across the

border, and it is not impossible that he will approach the subject with that

dogmatic assurance of a "little knowledge" which is sufficient to

be a "dangerous thing."

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHAP. v.] [WALES AND] HER LANGUAGE. 197

Mynyddislwyn School Board, for instance, took Welsh not long since. In the

only school under that Board, with which I am acquainted, it was a success,

the children were getting on well; but at the end of some five months,

without assigning a reason they stopped it, under an Englishman as chairman,

and one or more English members. It is true that one of the head-masters is

also an Englishman, and I heard he makes fun of their language to his Welsh

scholars. Perhaps the influence of the two combined, i.e., of two or three

ignorant persons who happened to be in positions of authority, was allowed to

turn the judgment of the Board back from the course on which it had entered.

I made it my business, shortly before hearing this, to call at another

Monmouthshire school where a different Board, though by no means warmly

attached to the Welsh idea gave the master liberty to teach Welsh as a

specific.

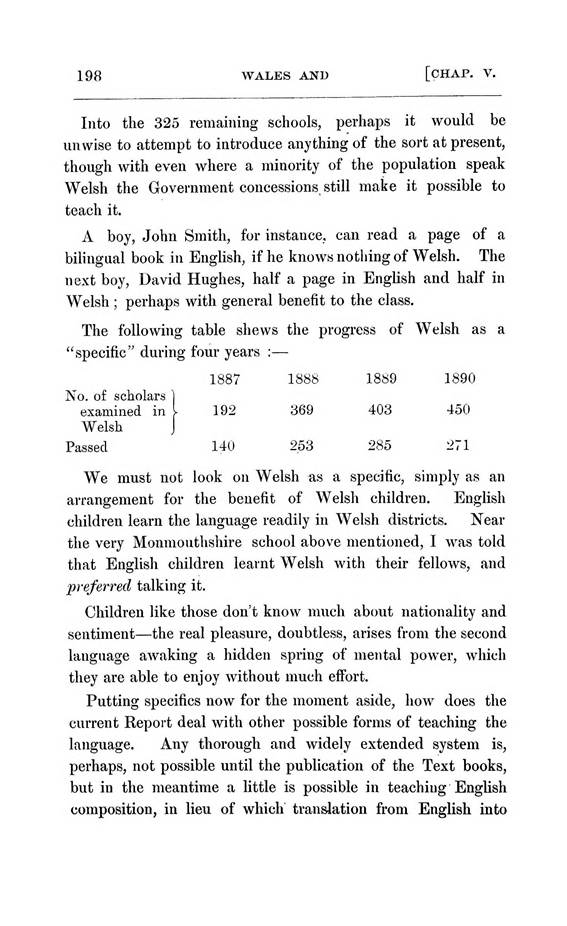

The sum of his testimony of the results of its introduction was:

1. That the children have a higher opinion of their language.

2. It is a success.

3. The children take an interest in it.

4. Their English is improved.

Now, if it is so in this school, why should it not be so in 1100 out of 1425

schools in Wales? Can anyone give a clear answer in the negative? I have read