1270e

Gwefan Cymru-

http://www.kimkat.org/amryw/sion_prys_033_safon_gymreig_1906_1317ke.htm

Yr Hafan / Home Page

..........1864e Y Fynedfa yn Gatalaneg /

Gateway in English to this website

....................0010e Y Gwegynllun

yn Saesneg / Siteplan in English

..................................Y Tudalen Hwn / This Page

|

|

Gwefan Cymru-Catalonia |

Adolygiad diweddaraf / Darrera

actualització 20 06 2000 |

![]() 0951k -

Cymraeg yn unig

0951k -

Cymraeg yn unig

The Grail / Volume 4, No. 13 (1911)

Tafodieithoedd Morgannwg

Gan T. Jones, Ysgol y Cyngor, Dunraven, Treherbert

The dialects of Morgannwg / Glamorgan, by T. Jones, The

Council School, Dunraven, Treherbert

Edrychid yn bur aml gan yr anwybodus a'r anghyfarwydd gyda gradd o

ddirmyg ar dafodieithoedd yn gyffredin fel rhywbeth y dylid eu hesgymuno o'r

tir. Cynhwysant, meddent hwy, y fath nifer o eiriau sathredig fel mai y peth

goreu i wneud ohonynt ydyw eu diarddel, a mabwysiadu iaith safonol yn eu lle.

Yn ffortunus fedrwn ni y Cymry ddim gwneud hyn oblegid ein tafodieithoedd ydyw

prif sylfaen ein holl ymddiddanion a'n llenyddiaeth.

Generally people

ignorant of and unfamiliar with dialects very often look on them with a degree

of contempt as something that has to be done away with ('excommunicated from

the land'). They contain, they say, so many debased words that the best thing

to do with them is disown them, and adopt a standard language in their place.

Fortunately we the Welsh cannot do this because our dialects are the cornerstone

('main foundation') of all our conversations and our literature

Mae gennym nifer o dafodieithoedd, a mwy fyth o is-dafodieithoedd, ond hyn sydd

ryfedd, fel mynn rhai gredu yn rhagoriaeth y naill dafodiaith ar y llall. Ac

We have quite a number of dialects, and even more

sub-dialects, but what is odd is how some people insist in believing in the

superiority of one dialect over another. And I know of no other kind of Welsh

spoken by the ordinary people of all the dialects of Wales which is the target

of so much contempt as the language of the inhabitants of Morgannwg is

Peth digon cyffredin yw clywed pobl Dyfed a Gwynedd yn difrïo iaith Morgannwg a

chyhoeddi ei hanghyfiawnderau a'i diffygion fel petae eu hiaith hwy yn safon

llên y genedl.

It's fairly usual to hear the people of Dyfed and

Gwynedd maligning the language of Morgannwg and exposing what is unjust about

it and its defects as if their language was the literary standard of the nation

Na, y mae gan y Wenhwyseg rai llenorion y medr ymffrostio ynddynt, pe enwid yn

unig Dafydd Benwyn, a beirdd Tir Iarll; pwy hyotlach ei bin na Ewart James,

awdwr yr Homiliau (1606), neu bwy ysgrifennodd cyn hardded Cymraeg a Thomas ap

Iefan o Drebryn, Morgannwg, neu bwy mwy llithrig a dyddorol na'r hynod Matthews

o'r Ewenni - prif nofelydd y Wenhwyseg fel y gwêl y neb a ddarlleno "Nyth

y Dryw" neu "Siencyn Penhydd."

No, the Gwentian dialect has some writers it can be

proud of, even if we were to name only Dafydd Benwyn, and the poets of Tir

Iarll; who wrote more eloquently ('who was more eloquent his pen') than Ewart

James, the author of 'Yr Homiliau' (= the Homilies) (1606), or who wrote in

Welsh as beautifully as Thomas ap Iefan from Tre-bryn, Morgannwg, or who [was]

more fluid [in style] and more interesting than the remarkable Matthews from Yr

Ewenni - the prime novelist in Gwentian as anyone who reads "Nyth y

Dryw" ('the wren's nest') or "Siencyn Penhydd" ('Siencyn of

Penhydd farm') can see.

Bu hefyd mewn bri nid yn unig lenorion ein gwlad, ond hefyd gan

bregethwyr Morgannwg. Ysgwaethiroedd, maent hwy bellach yn ei gwadu ac yn

ymarfer y Ddyfedaeg, neu yn dynwared y Wyndodeg gan dybio eu bod yn fwy yn y

ffasiwn, ac mai sarhâd ar eu dychymyg fyddai seinio yr a fain a'r

cydseiniau celyd. Nid oes, bellach, olynwyr i'r diweddar William Ifan o

Donyrefail, nac i William John o Benybont.

Not only the writers of our country were renowned, but

also Morgannwg preachers. Unfortunately they now reject it and make use of

Demetian (= the dialect of south-west

Llefarai rhain a nifer o'u cydoeswyr yn iaith gynhefin Morgannwg, a dyma un

rheswm dros eu llwyddiant gyda'r lluoedd. Da fyddai pe bae iaith y pwlpud yn

fwy cydweddol â'r iaith lafaredig.

These and a number of their contemporaries spoke in the

native language of Morgannwg, and that is one reason for their success with the

masses. It would be a good thing if the language of the pulpit was more in

keeping with the spoken language

Ond, er graddol farw o'r Wenhwyseg, ni chaiff ei geiriaduriaeth na'i

neulltuolion ieithyddol fynd ar ddifancoll. Yn hyd y blynyddoedd diwethaf yma

bu llawer o hel ar eiriau Morgannwg, a mawr y blas a gafwyd yn y gwaith.

But in spite of the gradual dying out ot Gwentian, its

lexicography and its linguistic peculiarities won't be lost for ever. In the

last few years there has been a great deal of collecting of Morgannwg words,

and it has been a very enjoyable task

Heblaw cael helfa dda o eiriau, cafwyd i'r ystên bopeth sydd yn anwyl gan bobl

y broydd a'r bryniau a garant swyn swn hen benhillion {sic} telyn, hen

ddiarhebion, ofergoelion, ystoriau pentan, chwedlau a llên gwlad. Os am ystên

lawn, ewch i'r encilion lle trig hen bobl a lle mae'r nwyd Gymreig yn bur ei

naws ac yn loyw fel y grisial.

Besides getting a good collection of words we've also

put in the jug with (note: the image is collecting bilberries in a jug on the

mountainside) everything held dear by the people of the uplands and the

lowlands who love to hear the old verses sung to the accompaniment of the harp

('harp verses'), superstitions, fireside stories, legends and country lore. If

you want a full jug go to those isolated spots where old people live and where

the Welsh passion is pure in nature and as bright as crystal

Yno, y clywch hwynt yn "wlîa" - nid ydynt yn

"siarad" neu barablu "jargon," ond yn chwedleua yn ôl arfer

yr hen Gymry. Ond o hir graffu, gwelir ddefnyddio ganddynt eiriau a brawddegau

cyn anhybyced i ardaloedd ereill o Gymru fel yr edrychid arni fel iaith arall

hollol.

There, you'll hear them using the word "wlîa"

(Note: this is the word in the south-east for 'to talk', in standard Welsh

'chwedleua', to relate accounts. In modern Welsh the standard words is

"siarad", from French "charade" from Occitan

"xarrada" = conversation) - they don't used the word 'siarad' or

speak 'jargon' - they use a form of the word 'chwedleua', the word used by the

Welsh people in olden times. But if you observe over a period, you'll see they

use words and sentences so unlike other areas of

Ac felly y mae mewn gwirionedd, mae treigliad amser wedi gwneud gwisg ei geiriau

yn fwy syml, ac wedi dwyn i fewn gyfnewidiadau tarawiadol iawn. Hefyd, mae

graddau y dirywiad yn mwyhau fel yr ewch o orllewin Morgannwg i'r dwyrain.

And so it is really, the passage of time has made the

outward appearance ('the dress') of the words simpler, and has brought in very

striking changes. Also, the extent ('degrees') of the decline increases as you

go from western Morgannwg to the east

I'r neb sydd erioed wedi talu rhith o sylw i'r Wenhwyseg, tarewir ef ar

unwaith â symlrwydd a phertrwydd ei hymadroddion. Nodweddir hi gan ryw urddas

cartrefol, mae iddi osgo chwimwth sydd yn cyd-fyned â meddwl cyflym y deheuwr.

Er amlyced yw hyn i'r rhai sydd yn gyfarwydd â'r iaith, ofnwn rhag eu cyhuddo o

bartiaeth yn canu ei chlodydd a dyfynnwn farn arall.

Anyone who has ever paid the least bit of attention to

the Gwentian is at once struck with the simplicity and attractiveness of its

expressions. It is characterised by a certain homely dignity, it has a rapid

gait which suits the quick mind of the southerner. Although this is so evident

to those familiar with the language, I'd be afraid of accusing them of bias

singing its praises and I'd quote another opinion.

Nid ydys yn traethu ond gwirionedd hen, a chaiff Wyndodwr ddatgan ei farn am ei

symlrwydd. Meddai y Dr. Pughe, mewn llythyr o'i eiddo i Mr. Cox, a ddyfynnir yn

"History of Monmouthshire," "The general character of this

dialect (i.e. the Gwentian) is a majestic simplicity, the expressions being

always full and free from contractions." Mae y dyb yma yn hollol gywir

oddigerth y frawddeg "free from contractions." Nid yw yn rhydd o'r

anffawd yma mwy nag unrhyw dafodiaith arall.

One is only expressing an old truth, and someone from

Gwynedd shall state his opinion on its simplicity. Dr. Pughe [a noted lexicographer

and grammarian], in a letter to Mr. Cox quoted in the "History of

Monmouthshire," "The general character of this dialect (i.e. the

Gwentian) is a majestic simplicity, the expressions being always full and free

from contractions." This supposition is completely correct except for the

phrase "free from contractions." It is not free of that unhappy trait

any more than any other dialect.

Eto, mae symudiadau ei brawddegau yn lled gyflym, mor gyflym na fedr mo'r

Gogleddwr eu deall hwy, a chwyna yn enbyd weithiau. "Cwyna yr olaf (sef y

Gogleddwr) eu bod yn methu deall gwyr y De, gan fuaned eu parabl; a phrin y mae

gan y Deheuwr ddigon o amynedd i wrandaw ar wyr y Gogledd, gan mor hirllaes ac

araf y torant eu geiriau" ("Llythyraeth yr Iaith Gymraeg," tud.

34, Silvan Evans, 1861).

Yet the movements of its sentences are fairly rapid, so

rapid that the northerner can't understand them, and sometimes complains

greatly. "The latter (that is, the northerner) complains he is unable to

understand the southerners, since they speak so fast; and the southerner is

hardly likely to have enough patience to listen to the northerners, since they

are so drawling and slow in saying their words. (Grammar of the Welsh Language,

page 34, Silvan Evans, 1861

Gorffwys parhad a defnyddioldeb unrhyw dafodiaith ar dri o alluoedd;

sef, gallu i hwyluso seiniau geiriau, gallu i fabwysiadu a chydweddu geiriau

newyddion ac estronol, a gallu i gadw geiriau oesoedd cynt yn ei meddiant. Wedi

ymchwil manwl gellir dweyd fod pobl Morgannwg wedi llwyddo i wneud hyn tu hwnt

i fesur.

The continuance and usefulness of any dialect depends

on three abilities, namely, the ability to make the sounds of words easier, the

ability to adopt and assimilate new words and foreign words, and the ability to

keep words from past ages in its possession. After detailed research it can be

said that the people of Morgannwg have managed to do this beyond measure

Mae yn eu meddiant ddigon o eiriau - rhai miloedd mewn gwirionedd. Mae eu

hiaith yn gyfoethog o eiriau tlysion, swynfawr; mae yn doreithiog o eiriau

sarrug a thaiog; mae ganddi chwedleuon parod ac atebion parotach fyth, a stôr o

cyffelybiaethau a geiriau deublyg; ie, mae ynddi ddigon o ynni a rhamant i fod

eto o ddefnydd parhaol.

It has in its possession enough words - many thousands

in fact. Its language is rich with splendid and attractive words; it has an

abundance of sour and churlish words; it has a stock of tales and repartee

('ready tales / legends and even readier answers'), and a store of similes and

words with double meanings; yes, there is enough energy and romantic features

in it to still be of enduring use

Pan gofir safle ddaearyddol Morgannwg, natur arwynebedd y fro, - cyn agosed

ydoedd i ymosodiadau y gelyn ac i'r llanw Seisnig, - y syndod yw pa fodd y

galluogwyd hi i wrthsefyll yn erbyn cefnllif y Sacson, y Norman, a'r Sais,

heblaw sôn am oresgyniad masnachol ein dyddiau ni.

When the geographical position of Morgannwg is

considered ('remembered'), the nature of the surface of the lowland - it was so

close to the attacks of the enemy and the influx ('tide') of English - the

surprise is how it was enabled to resist in the face of the flood of Saxons,

Normans, and English, not to mention the economic conquest of our days

Cyn dechreu o'r Goresgyniad Masnachol tua 1760-1795, cawn taw Cymraeg

bur oedd i'w chlywed hyd a llêd y sir. Dyma'r gwrthwynebedd a'r difrodydd mwyaf

andwyol ar yr Wenhwyseg. Newidiodd y dull o fyw, cymerodd masnach lofaol le yr

amaethyddol, a chafodd hyn, felly, effaith ddistrywgar ar fywyd ac iaith

amaethyddol y sir. Ond hyd yn oed pe canieteid hyn, mae ynddi eto ddigon o

undeb corfforol i'w gwneud yn allu nerthol yn y tir.

Before the Economic Conquest around 1760-1795, we find

that pure Welsh has to be heard the length and breadth of the county. This is

the most damaging adversity and destruction that has affected Gwentian ('on the

Gwentian'). The style of life chance, the coal trade took the place of

agricultural trade, and so this had a destructive effort on the agricultural language

and life of the county. But even if this is permitted, there is i it yet enough

physical unity to make it a strong power in the land

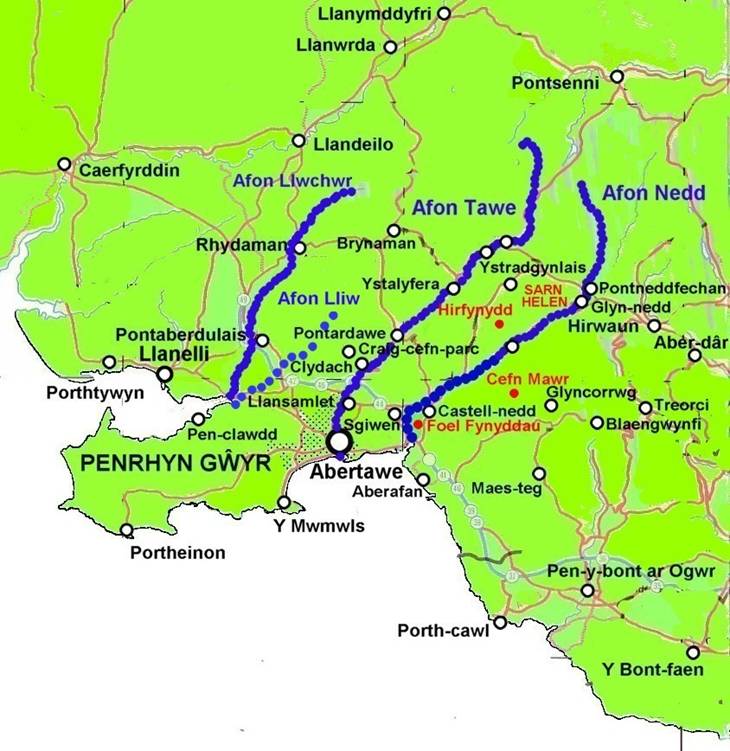

Hwyrach cawn fwrw golwg agosach ar ffiniau tafodieithoedd Morgannwg a'u

neilltuolion ieithyddol. Byddai unrhyw ymdrech ar hyn o bryd i nodi yn gywir y

ffiniau yn anfoddhaol o herwydd prinder defnyddiau at y gwaith. Ond cyn belled

ag yr â sylwadaeth ac ymchwiliad mae yma dair tafodiaith amlwg, sef, y

Wenhwyseg Bur, neu dafodiaith Blaena a Bro Morgannwg, tafodiaith Cwm Nedd, a

thafodiaith Cwm Tawe. Penderfynnir pob ffin yn ôl rhyw arwyddion ieithyddol, a

cheisiwn eu nodi.

Later we shall take a closer look at the boundaries of

the dialects of Morgannwg and its linguistic traits. Any attempt at present to

note the boundaries exactly would be unsatisfactory because of the lack of

materials for the work. But so far as commentaryand investigation goes there

are three obvious dialects, namely, Pure Gwentian, or the dialect of the

Blaenau and Bro Morgannwg (the Morgannwg uplands and lowlands), the dialect of

Cwm Nedd (the valley of Nedd / Neath). Each boundary is decided by certain

linguistic indications, and we'll try to note them.

Mae sain y llafariad a yn penderfynnu un ffin. Cofier fod dwy a

ym Morgannwg, y naill yn hir a'r llall yn fain. Ceir y cyntaf i'r gorllewin o'r

Cefn Mawr a'r Foel Fynyddau, a'r a fain (nodir hi yn yr ysgrif fel ä)

i'r dwyrain o'r un ffin. Perthyn y cyntaf i'r Ddyfedaeg, ond mae'r a fain

yn briodoledd neilltuol o'r Wenhwyseg Bur.

The sound of the vowel a decides one boundary.

Remember that there are two a's in Morgannwg, one long and the other 'narrow'.

The first is found to the west of the Cefn Mawr (= big hill / big ridge) and

the Foel Fynyddau (= bare mountains), and the narrow a (in this article

we write it ä) to the east of this boundary. The first belongs to

Demetian (Note: the dialect of Dyfed, or south-west

Cyfetyb hefyd i

"â" y Gernywaeg a thebyg ydyw i frefiad dafad, yr un ag a geir yn y

Seisnig baa. Dywed Mr. Jenner yn ei lawlyfr ar y Gernywaeg am yr

"ä" yma fel hyn, "â long, the lengthened sound of a short,

not as the English broad a i father, or long a in name...

Thus bâ would have something between the sound of the English bare in

the mouth of a correct speaker and the actual sound of the bleat of a sheep

(Handbook of the Cornish Language, by H. Jenner, p. 56).

It also correponds to the Cornish "à" and it

is similar to the bleat of a sheep, the same as you have in the English baa.

Mr. Jenner in his handbook on Cornish says this about the "â" -

"â long, the lengthened sound of a short, not as the English broad a

i father, or long a in name... Thus bâ would have

something between the sound of the English bare in the mouth of a

correct speaker and the actual sound of the bleat of a sheep (Handbook of the

Cornish Language, by H. Jenner, p. 56).

Petae Mr. Jenner yn un o wyr y Gloran, neu o wyr y Fro,

If Mr. Jenner was one of the 'people of the Gloran' (a

nickname for

Mae trigiant yr a fain,

fel y dywedwyd eisoes, i'r dwyrain o'r Cefn Mawr sydd rhwng Cwm Nedd a Chwm yr

Afan {sic; = Cwm Afan}. Cynnwys y ffin yma sy'n rhedeg o'r Kenffig {sic: =

Cynffig}, ar hyd drum u Cefn Mawr, hyd at Aberdâr a Merthyr, gymoedd poblog

Morgannwg, sef yr Afan, Corrwg, y Garw, Ocwr, Lai, Rhondda, Cynon, Taf, a Rhymi,

a bro Morgannwg.

The location of the 'narrow "a"' as we have

already said, is to the east of the Cefn Mawr which is between Cwm Nedd (the

Nedd valley, the Neath valley) and Cwm Afan (the Afan valley). This boundary

which runs from Cynffig ('Kenffig'), along the ridge of the Cefn Mawr, as far

as Aberdâr and Merthyr, includes the populous valleys of Morgannwg (Glamorgan),

namely the Afan, Corrwg, Garw, Ocwr (= local form of Ogwr), Lai ('Ely'),

Rhondda, Cynon, Taf, a Rhymi (= local form of Rhymni), and the lowland of

Morgannwg ('the Vale of Glamorgan')

Adnabyddir y mynyddoedd ym mhen uchaf y sir fel y "Bleinia"

(Blaenau). Bu llawer ymgyrch rhwng "Gwyr y Bleinia" a "Gwyr y

Fro" nes aeth yn "wetiad" gan yr olaf, "Myswynoch rhog Gwyr

y Bleinia," neu "Myswynoch rhog Gwyr y Fro," neu "Myswynoch

rhog Gwyr y Gloran," - trigolion Cwm y Rhondda yr rhai {sic} oedd yn

nodedig am wneud difrod ar feusydd ffrwythlon y Fro, a dwyn eu gwartheg

blithion.

The mountains at the top end of the county are known as

the "Bleinia" (standard form - Blaenau. This means 'uplands'). There

was much fighting between the "Gwyr y Bleinia" (uplnad people) and

the "Gwyr y Fro" (lowland people) until it became a

"wetiad" (Gwentian form of "gwediad / dywediad" = saying)

with the latter, "Myswynoch rhog Gwyr y Bleinia," (= Ymswynwch rhag

Gwyr y Blaenau = cross yourself / make the sign of the cross to protect you

from the upland people), "Myswynoch rhog Gwyr y Fro," (...against the

lowland people) or "Myswynoch rhog Gwyr y Gloran," (...against the

Gloran people) - the inhabitants of the Rhondda who were notorious for wreaking

damage fertile fields of the Lowland, and stealing their fat cattle

I'r gorllewin o'r ffin yma y mae gwyr Castell Nedd, neu fel yr adwaenid

hwy ar lafar gwlad "Gwyr y Mera." Ni fynnai gwyr y Fro gael un

cyfathrach â hwynt, oblegid

"Yr Abbey Jacs a'r Mera breed

'Dos dim o'u bäth nhw yn y byd."

To the west of this boundary are the people of

Castell-nedd, or as they are known colloquially "Gwyr y Mera" [the

people of the 'Mera']. The inhabitants of the lowland / the Vale of Glamorgan

wanted nothing to do with them, because

"The Abbey Jacks and the Mera breed

There's nothing like them in the world" [Abi-Jacs = inhabitants of

Mynachlog-nedd ('Neath Abbey')

Penderfynnir y ffin nesaf yn ôl y modd y defnyddir "a" neu

"e" yn sill olaf geiriau. Mae sylwi ar ynghaniad y gair bach

"ia" neu "ie" yn ddigon i'n dwyn i gasgliad lled gywir. Ac

er ychwanegu y prawf sylwer ymhellach sut yr ynghaner y geiriau ac

"a" yn y sill olaf - pa un ai "petha" ynte

"pethe"; "llawan" ynte "llawen," ac yn y blaen.

Fe'n cynhorthwyir yma gan ffeithiau ereill, sef arwynebedd y tir, a

phwysigrwydd trefydd Abertawe a Chwm Nedd.

The next boundary is decided by the way that

"a" or "e" is used in the last syllable of words. Observing

the little word "ia" or "ie" is enough to bring us to a

fairly accurate conclusion. And in order to have further proof note ('in order

to add the proof observe further' how words with "a" i the final

syllable - whether it is "petha" or "pethe" [= things],

"llawan" or "llawen" [= merry], and so on. We are aided

here by other facts, that is the area of the land, and the importance of the

towns of Abertawe (Swansea) and Cwm Nedd (the Nedd / Neath valley)

Mae cors wlyb Crymlin yn un pen o'r ffin rhwng tafodiaith Cwm Nedd a

thafodiaith Cwm Tawe, ac y mae pwysigrwydd marchnataol Abertawe a Chwm Nedd yn

penderfynnu i raddau, rhediad y ffin o'r gors ymlaen, rhwng Llansamlet a

Sciwen. Mae yn ymrannu yn agos i Cwmdu {sic}, ac oddiyno â i'r Hirfynydd, gan

ddilyn Sarn Helen hyd at Bont Nedd Fechan.

The wet bog of Crymlyn at one end of the boundary

between the dialect of Cwm Nedd and the dialect of Cwm Tawe (the valley of the

Tawe), and the economic importance of Abertawe (

I'r dwyrain o'r ffin

yma yr "a" sydd gyffredin, megys "ia," "llawan,"

"patall" (padell), "catar" (cadair).

"Tri pheth sy'n llonni'r bachan,

Gweld gwraig y ty'n llawan," etc

to the east of this boundary the "a" is

general, such as "ia" [= yes], "llawan" [= merry], "patall"

(padell) [= pan], "catar" (cadair) [= chair].

"Three things which cheer the lad / see the woman of the house

merry", etc

I'r gorllewin o'r un ffin yma "e" sydd gyffredin.

Nodwedd neilltuol iawn o eiddo holl dafodieithoedd Morgannwg ydyw caledu'r seiniau

meddal - g, b, d - i fod yn rhai celyd - c, p, t - megys "maci"

(magu), "popi" (pobi), "catw" (cadw). Ceir y seiniau yn

niwedd geiriau deusill. Clywir yr acen galed yma o Afon Lliw hyd Sir Fynwy

To the west of this same boundary "e" is

general. A very special trait belonging to all the dialects of Morgannwg is the

hardening of the soft sounds - g, b, d - to be hard ones - c, p, t - as

"maci" (magu) [= to bring up, to breed], "popi" (pobi) [=

to bake], "catw" (cadw) [= to keep]. The sounds are found at the end

of two-syllable words. This hard accent is heard here from Afon Lliw ('the Lliw

river') to Sir Fynwy ('Monmouthshire').

Ni ddaw tafodiaith Gwyr o fewn ein hystyriaethau, oblegid ychydig iawn o

Gymraeg sydd is law "Penclôdd," ys dywed gwragedd Gwyr.

Gwelir oddiwrth y sylwadau uchod fod yna dair tafodiaith yn ffynnu ym

Morgannwg; sef y Wenhwyseg, yr hon a gynnwys yr a fain, y ddiweddeb a, a'r a yn

y goben; tafodiaith Cwm Nedd, yr hon sydd debyg i'r Wenhwyseg oddigerth nad oes

ganddi mo'r a fain; a thafodiaith Cwm Tawe, lle ffynna dim ond un

nodwedd neilltuol o'r Wenhwyseg, sef y cydseiniau celyd.

The dialect of Gwyr [= Gower] won't come into our

considerations, because there is very little Welsh below "Penclôdd,"

as the women of Gwyr say.

From the above we see that there are three dialects thriving in Morgannwg;

Gwentian which has the narrow 'a', the ending 'a', and the 'a' in the

penultimate syllable (??); teh dialect of Cwm Nedd, which is similar to

Gwentian except that it doesn't have the 'narrow a'; and the dialect of Cwm

Tawe [the valley of the Tawe], where only one special feature of Gwentian

flourishes, namely the hard consonants.

Y mae yn orchwyl dyrys ddigon i chwilio allan nodweddion gramadegol

unrhyw dafodiaith fyw, ond ceisiwn er hynny enwi rhai o bwyntiau amlycaf

seiniau y llafariad {sic} a'r cydseiniau, ac y diweddwn hyn o lith trwy roddi

rhai geiriau henafol y Wenhwyseg.

It's a fairly complicted task to search out the

grammatical characterisitcs of any living dialect, but in spite of this we'll

try to point out some of the most prominent points of the vowel and consonant

sounds, and we'll end this article by giving some ancient Gwentian words

Pareblir a, e ac i yn amlwg a chlir; mae yr a cyn

amlyced fel nad amhriodol fyddai galw'r Wenhwyseg yr a dafodiaith; y mae

e y goben yn hir, e.g., mêlîn ac nid mêlin fel yn Ddyfedaeg; nid oes un

gwahaniaeth rhwng i, u, ac y - seinir hwynt fel i; mae'r o

yn debyg i'r o yn y geiriau Seisnig note, vote, megys gôfin,

ôfan (ofn), ond y mae o o flaen n ac r yn fyrr, megys llonni, torri.

[The sounds] a, e and i are spoken prominently and

clearly; the a is so prominent that it isn't inappropriate to call Gwentian the

'a' dialect; the 'e' of the penultimate syllable is long e.g., mêlîn [= mill]

and not mêlin as in Demetian; there's no difference between i, u, and y

- they are pronounced like i; the o is simila to the o in

the English words note, vote, as gôfin [gofyn = to ask], ôfan (ofn) [=

fear], buto in front of n and r is short, like llonni [= cheer up], torri

[= to break].

Yr mae'r o yn hollol annhebyg i o y Ddyfedaeg. Y mae

llafariad o flaen llt, sc, sp ac st yn fyrion, megys mêllt, Pâsc,

llîsc (llusg), clîst. "Ymddengys," meddai Silvan Evans, "fod y

dull hwn yn fwy cysson â theithi y Gymraeg, ac â chyfaledd ieithoedd yn

gyffredin" ("Llythyraeth yr Iaith Gymraeg," tud. 33). Try a,

e ac i i'r llefariad {sic} dywyll (obscure vowel) yn aml iawn, ond

gan nad oes ond yn unig gofod i'w grybwyll awn heibio iddi.

the o is quite different o tthe o in Demetian. The

vowel o before llt, sc, sp and st is short, as in mêllt [=

flashes of lightning], Pâsc [= Easter], llîsc (llusg) [= dragging], clîst [=

ear]. "It seems," says Silvan Evans, "that this way is more in

keeping with the traits of Welsh, and with the analogy of other languages in

general" ("Grammar of Welsh," page 33). The letters a, e

and i tuen into the obscure vowel very frequently, since there is only

space to give it a mention we'll pass it by

Eto, gair ar y cydseiniau. Mae d yn cael ei dilyn gan i yn troi

yn "ji", megys jiofadd (dioddef); jiocal (diogel); aiff

f ar goll yn lled aml, ac y mae h bron darfod a bod yn llythyren

fyw os na fydd angen am bwyslais neilltuol, e.g. y nhw yn ("nhw"),

dihîna, a phan yn dilyn y rhagenw ym dodir h i fewn, e.g. ym harian

i, ym hallwath i; ond mae wedi ei llwyr golli mewn rhai geiriau, megis ar

wa'än, gwaniath (gwahaniaeth),a dîno (dihuno).

Again, a word about the consonants - d followed by i

changesinto ji, such as jiofadd (dioddef) [= suffer], jiocal (diogel) [= safe].;

f is frequently lost, and h has lamost ceased to be a living letter if there is

no need for special emphasis, e.g. the combiniation nhw in the word

"nhw" [they], dihîna [dihuna = wake up!], and when it follows the

pronoun ym an h is put in, e.g. ym harian i [= my money], ym

hallwath i [= my key]; but it has been completely lost in some words such as ar

wa'än [ar wahân = apart, separate], gwaniath (gwahaniaeth), [= difference], and

dîno (dihuno) [= to wake up].

Try s yn sh pan (1) yn gyfartal â si, neu ji neu ja yn

Seisnig; (2) mewn geiriau unsill, megys mish (mis), prish (pris), (3) ynghanol

geiriau - mishol, tishan (teisen) shishwrn (scissors); ac (4) pan bo d neu

t yn cael eu dilyn gan i, neu u, megys, scitsha

(esgidiau), tsha (tua). Mae rhai geiriau, serch hyny, wedi arbed y dirywiad

yma, megys siwr (sywr, ac nid shiwr na shwr), plêsar, swgir, crîs (crys), cros

(croes), tros.

The sound s becomes sh when (1) it is equiva,ent to si,

or ji or ja in English; (2) in monosyllable words, like mish

(mis) [= month], prish (pris) [= price], (3) in the middle of words - mishol [=

monthly], tishan (teisen)[= cakes], shishwrn (scissors); and (4) when d or

t are followed by i, or u, as, scitsha (esgidiau) [=

shoes], tsha (tua) [= towards]. In spite of that, some words have been spared

this debasement, such as siwr (sywr, and not shiwr or shwr) [= sure], plêsar [=

pleasure], swgir [= sugar], crîs (crys) [= shirt], cros (croes) [= cross], tros

[= over].

Nodwn, cyn tynnu i'r terfyn, rai geiriau glywir bob dydd, rhai am eu

hynodrwydd, ereill am eu henaint, ac ereill am eu dyddordeb cyffredinol. Hyd yn

oed yn eu cyfarchiadau beunyddiol tynnant ein sylw. Wele atebion i'r cyfarchiad

syml, "Shwd ych chi heddy?" - "Iownda" neu "Iownda

dä" neu "Ionwda drwg" neu "Piwr diginnig" neu

"Tlawd a Bälch" {sic; ond yn sicr ddigon "balch", nid

"bälch"

.

We shall note, before drawing to a close, some words heard every day, some

because of their remarkability, and others for their general interest. Even in

their daily greetings they draw our attention. Here are responses to the simple

greeting "How are you today?" "fairly (good)" or

"fairly good" or "fairly bad" or "extremely well"

('incomparably pure') or 'poor and proud'.

Ereill a'n hatgoffa ni pan oedd addoli Mair a Phabyddiaeth yn nerthol yn

ein gwlad, megys "ma'n gorwadd dan i grwys,” " Mäb Mair i'th

ran," "Arîa!" (Ave Mair neu Ave Maria), a'r "Fari

Lwyd" neu y "Feri Lwyd" fel y gelwid hi yn y Fro. Wele

frawddegau eto sy'n dwyn ein meddyliau yn ôl i'r Canoloesoedd: "Dir dalo

iti" (Duw a dallo itt Mabinogion). "Rhäd Duw ar y

gwaith," "Bendith Duw ar y gwaith," ac feallai "Dir di

shefoni'n brudd."

Others remind us of when the worship of Mary and

Catholicism was a powerful force ('was powerful') in our country, such as

"ma'n gorwadd dan i grwys”, [mae ef yn gorwedd o dan ei grwys = he's laid

out for burial 'he's lying under his cross'], " Mäb Mair i'th ran, "

[Mäb Mair i'th ran = may the son of Mary be with you 'the son of Mary to your

part'], "Arîa!" (Ave Mair neu Ave Maria), and the "Fari

Lwyd" or the "Feri Lwyd" as it was called in the Lowland. [Holy

Mary, literally 'grey Mary', a wooden horse's head used in Christmas

celebrations]. Here are some more senteneces which take our thoughts back to

the Middle Ages - "Dir dalo iti" (Duw a dalo itt Mabinogion)

[may God pay you]. "Rhäd Duw ar y gwaith," [= the grace of God on the

work], "Bendith Duw ar y gwaith," [= the blessing of God on the work]

and maybe "Dir di shefoni'n brudd." ['may God claim us (or: our

lives) seriously'

I'r sawl a garai'r gwaith o'u casglu mae toraeth dda o hen eiriau y

Mabinogion yma, ond rhoddwn ychydig o honynt, megys - ys, y rhagenw

"i" ac nid ei, y diweddeb ws o wys y Mabinogion, gwaith yn golygu

effaith, rhog (rhag), i miwn (i mywn, Mabinogion), i mäs (i maes, Mabinogion),

diwetidd (diwedd dydd, Mabinogion), i fynidd (i vynydd, Mabinogion),

siwr (Med. W. sywr) {= Medieval Welsh}, whech, whär (whaer), cymrid (cymryd, Mabinogion),

gwilad (gwylat, Mabinogion) cwplo cwpla (cwplaf, P.K. , Mabinogion),

hiol O.W. hoil) {= Old Welsh}, pilgin (pylgein), pwysig (weighty, Lat., pensum)

{Latin

,

ñ {For those who like the work of collecting them, this is a great abundance of

old words from the Mabinogion here, and we shall give a few of them, such as - ys

(= is), the pronoun [poessesive] "i" and not ei, the ending ws

from the form wys found in the Mabinogion, "gwaith" meaning

"effect" [usually = work], rhog (rhag) [0 for], i miwn (i mywn, Mabinogion)

[= inside], i mäs (i maes, Mabinogion) [= outsied], diwetidd (diwedd

dydd, Mabinogion) ['diwetydd' = 'end-day', i.e. afternoon], i fynidd (i

vynydd, Mabinogion) [i fynydd = up], siwr (Medieval Welsh sywr) [=

sure], whech [chwech = six], whär (whaer) [= sister], cymrid (cymryd, Mabinogion)

[cymryd = to take], gwilad (gwylat, Mabinogion) [gwylied = watch over],

cwplo cwpla (cwplaf, P.K. , Mabinogion), [cwblháu = finish] hoil O.W.

houl) {= Old Welsh} [haul = sun] pilgin (pylgein) [plygain = midnight mass],

pwysig (weighty, Lat., pensum) {Latin} [pwysig = important],

briwo (to pound small) (Lludd a Llefelys), digoni ("or druc

digonit," BBC), cyflwyna (to take presents, M.W. cyflwyn), gorod (gorfod,

"gorfod cymod â thi." Myf. Arch., tud 58), diwarnod (diwarnawd, Mabinogion),

yma lle, yna lle (Ac ene lle y Kerdus enteu ar wyr powys." Hanes G. ap

Cynan), rhacod

("Gwaith teg yw marchogaeth ton.

I ragod pysg o'r eigion.")

(D. ap Gwilym) {= Dafydd ap Gwilym}, ys llawer didd a llwffan (Med W lloppaneu)

{= medieval Welsh}.

briwo (to pound small) (Lludd a Llefelys), digoni

("or druc digonit," BBC) (= bake), cyflwyna (to take presents, M.W.

cyflwyn), gorod (= be obliged) (from gorfod, as in "gorfod cymod â

thi." = be obliged to be reconciled with you. Myfyrian Archaeology page

58), diwarnod (= day) (diwarnawd, Mabinogion), yma lle, yna lle (Ac ene lle

y Kerdus enteu ar wyr powys." Hanes Gruffudd ap Cynan ), rhacod (= ambush,

waylay; in Morgannwg = save, protect; prevent from doing sth, stop from doing

sth)

("Gwaith teg yw marchogaeth ton.

I ragod pysg o'r eigion.") (= Ride a wave is fair work, to catch a fish

from the ocean)

(D. ap Gwilym) {= Dafydd ap Gwilym}, ys llawer didd a llwffan (Medieval Welsh

lloppaneu) (=?? Morgannwg scitsha'n lwffan = [of shoes] be too loose

Gwelir, oddiwrth hyn o lith gymaint ddyddordeb sydd yn y Wenhwyseg i'r

ieithyddwr, ac hyd yn oed, i'r darllennydd cyffredin.

There can be seen from this article how much interest

there is for the linguist in Gwentian, and even for the general reader

(DIWEDD / END)

_________________________________________

DOLENNAU AR GYFER GWEDDILL EIN

GWEFAN / LINKS TO THE REST OF THE WEBSITE

1004e

Y Wenhwyseg - iaith Gwent a Morgannwg

Gwentian - the dialect of Gwent and Morgannwg

·····

1051e

mynegai i destunau Cymraeg â chyfieithiadau Saesneg

index to Welsh texts with English translations

·····

0223e

yr iaith Gymraeg

the Welsh language

Ble’r wyf i? Yr ych chi’n ymwéld ag un o

dudalennau’r Gwefan “CYMRU-CATALONIA”

On sóc? Esteu visitant una pàgina de la Web “CYMRU-CATALONIA” (=

Gal·les-Catalunya)

Weø(r) àm ai? Yùu àa(r) vízïting ø peij fròm dhø “CYMRU-CATALONIA” (=

Weilz-Katølóuniø) Wéb-sait

Where am I? You are visiting a page from the

“CYMRU-CATALONIA” (= Wales-Catalonia) Website

CYMRU-CATALONIA