kimkat0374k Lectures on Welsh Philology.

1877. John Rhys (1840-1915).

16-05-2018

● kimkat0001 Yr Hafan www.kimkat.org

● ●

kimkat2001k Y Fynedfa Gymraeg www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_gwefan/gwefan_arweinlen_2001k.htm

● ● ● kimkat2194ke Cyfeirddalen yr Adran Ramadeg http://kimkat.org/amryw/1_gramadeg/gramadeg_cyfeirddalen_2194k.htm

● ● ● ● kimkat0369k

Lectures On Welsh Philology – Y Gyfeirddalen www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/testunau-saesneg_175_welsh-philology_john-rhys_1877_0373k.htm

● ● ● ● ● kimkat0374k Y tudalen hwn

...

|

|

|

Gwefan Cymru-Catalonia |

|

...

Tudalennau blaenorol:

Rhan 1 Tudalennau 0-99

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/testunau-saesneg_175_welsh-philology_john-rhys_1_1877_0369k.htm

Rhan 2 Tudalennau 100-299

www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_testunau/testunau-saesneg_175_welsh-philology_john-rhys_2_1877_0372k.htm

llythrennau cochion = testun heb ei

gywiro

llythrennau duon = testun wedi ei gywiro

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURES ON

WELSH PHILOLOGY. |

|

|

|

|

|

300 LECTUEES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. Ogam on the stone now occupying

our attention is to be regarded as making one name Awwiboddib- or Awwi

Boddib-, it must mean ' Nepotis Bodi-bevi.' The only thing which prevents me

from reading the whole thus: Bewwlf] Awwi Boddi-blewwi], " B. nepotis

Bodibevi," is the fact that it is not usual to begin with the right

edge; but that is perhaps not a sufficient reason for not doing so here. This

remarkable stone, then, commemorates either two or three distinct persons,

who are shown, however, to have belonged to the same family by the

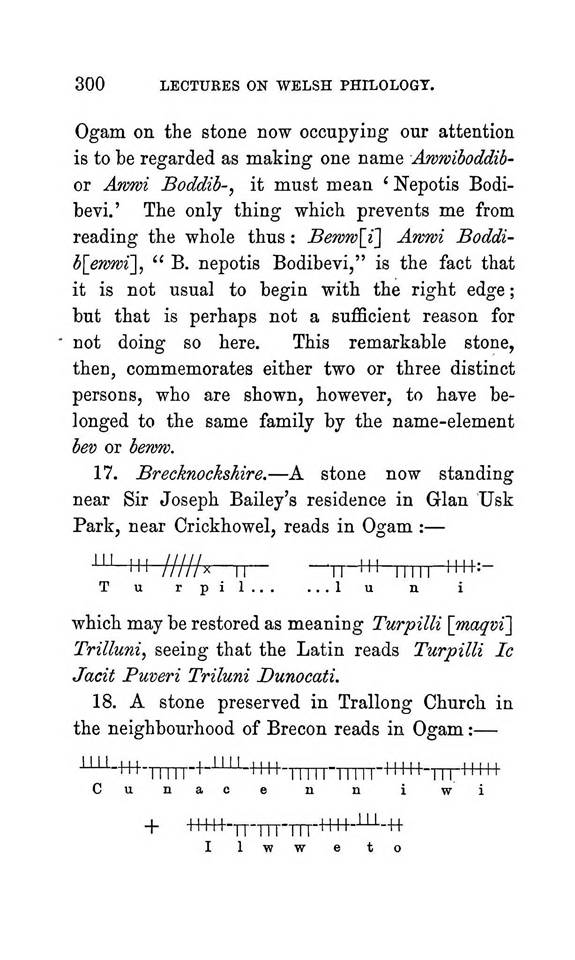

name-element bev or bewm. 17. Brecknockshire. — A stone now standing near Sir

Joseph Bailey's residence in Glan Usk Park, near Crickhowel, reads in Ogam: —

' " 1 1 1 /////x I I -n II I II I =- T u rpil... ...1 u n i which may be

restored as meaning Turpilli [maqvi] Trilluni, seeing that the Latin reads

Turpilli Ic Jacit Puveri Triluni Bunocati. 18. A stone preserved in Trallong

Church in the neighbourhood of Brecon reads in Ogam: — Cuuace n n i wi +

+^+H-7T-T^-T^^^^^^-^-++ I 1 w w e to |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 301 The Latin reads: — CVNOCENNI FILIVS CVNOCENI HIC

lACIT, whence it would seem that Cunacennini is a kind of patronymic meaning

C. filius C, and that Ilwmeto is an epithet. The broader end of the stone

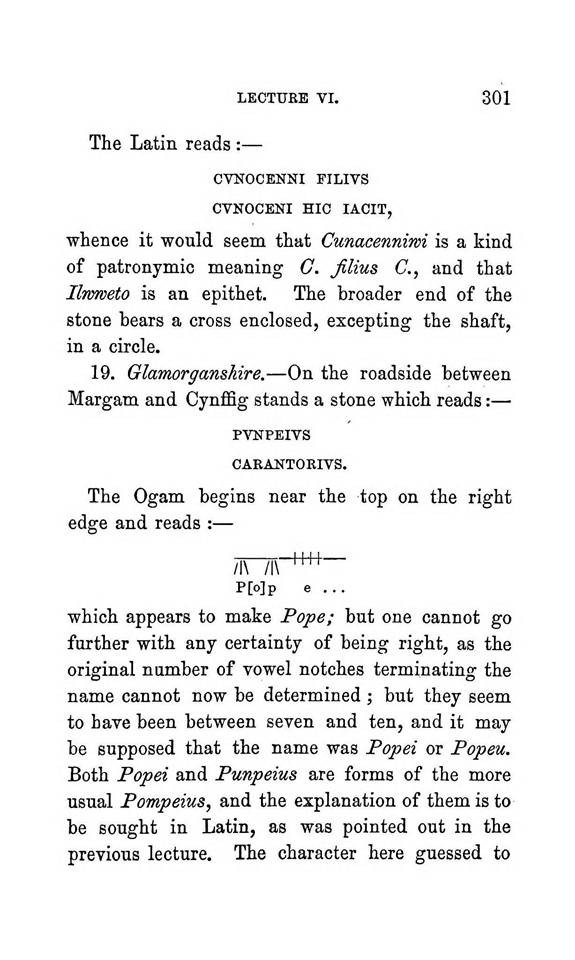

hears a cross enclosed, excepting the shaft, in a circle. 19. Glamorganshire.

— On the roadside between Margam and Cynffig stands a stone which reads: —

PYiTPEIVS CARANTORITS. The Ogam begins near the top on the right edge and

reads: — P[o]p e ... which appears to

make Pope; but one cannot go further with any certainty of being right, as

the original number of vowel notches terminating the name cannot now be

determined; but they seem to have been between seven and ten, and it may be

supposed that the name was Popei or Popeu. Both Popei and Punpeius are forms

of the more usual Pompeius, and the explanation of them is to be sought in

Latin, as was pointed out in the previous lecture. The character here guessed

to |

|

|

|

|

|

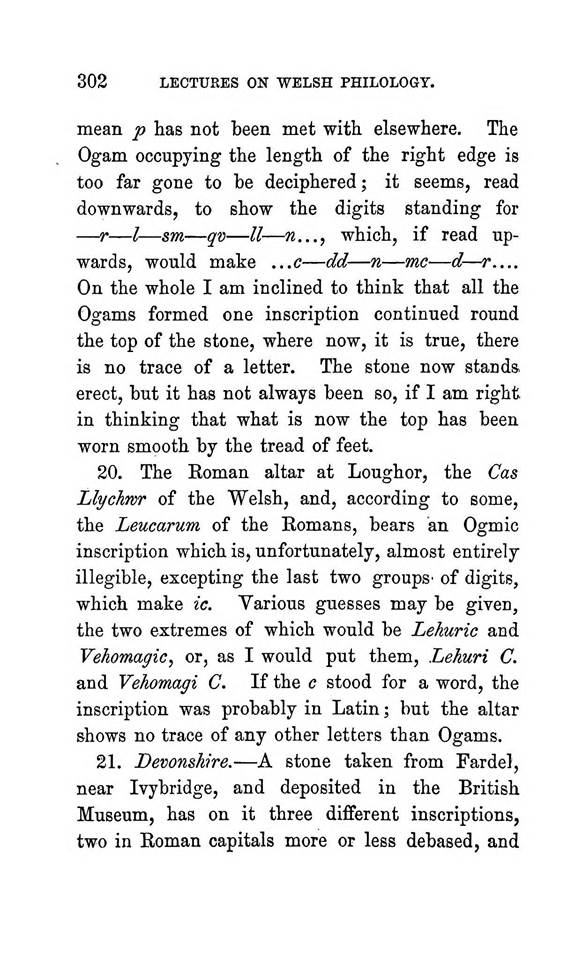

302 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. mean p has not been met with

elsewhere. The Ogam occupying the length of the right edge is too far gone to

be deciphered; it seems, read downwards, to show the digits standing for — r

— I — sm — qv — II —?z..., which, if read upwards, would make ...c — dd — n —

mc — d — r.,.. On the whole I am inclined to think that all the Ogams formed

one inscription continued round the top of the stone, where now, it is true,

there is no trace of a letter. The stone now stands erect, but it has not

always been so, if I am right in thinking that what is now the top has been

worn smooth by the tread of feet. 20. The Eoman altar at Loughor, the Cas

Llychwr of the "Welsh, and, according to some, the Leucarum of the

Eomans, bears an Ogmic inscription which is, unfortunately, almost entirely

illegible, excepting the last two groups' of digits, which make ic. Various

guesses may be given, the two extremes of which would be Lekuric and

Vehomagic, or, as I would put them, Lehuri C. and Vehomagi C. If the c stood

for a word, the inscription was probably in Latin; but the altar shows no

trace of any other letters than Ogams. 21. Devonshire. — A stone taken from

Fardel, near Ivybridge, and deposited in the British Museum, has on it three

different inscriptions, two in Eoman capitals more or less debased, and |

|

|

|

|

|

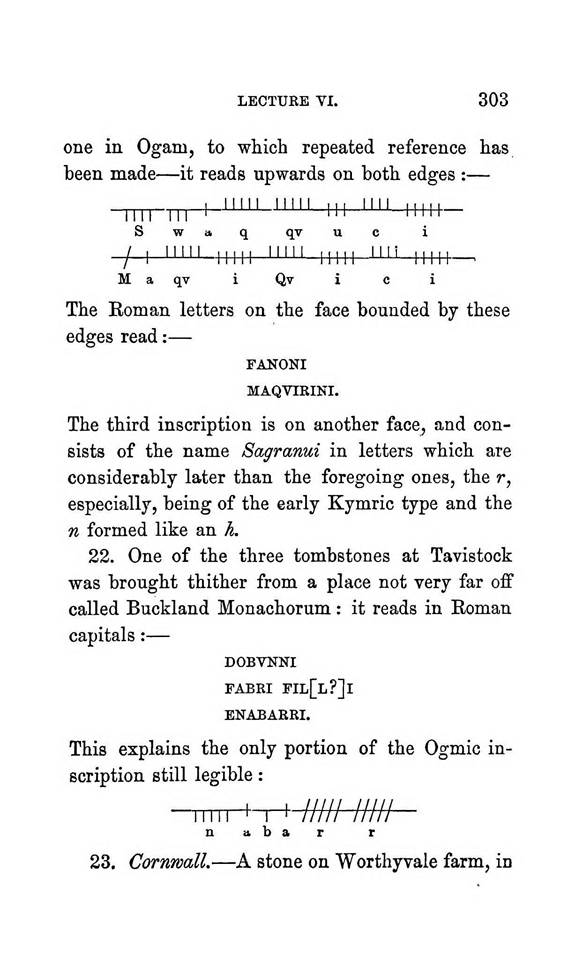

LECTURE TI. 303 one in Ogam, to which repeated reference has been

made — it reads upwards on both edges: — nil III! 'I' ll III I I I! mil -

Swaq qvuc i / I mil inn m" mi l n" i ii ii -^ M a qv i Qv i c i The

Koman letters on the face bounded by these edges read: — FANONI MAQVIRINI.

The third inscription is on another face, and consists of the name Sagranui

in letters which are considerably later than the foregoing ones, the r,

especially, being of the early Kymric type and the n formed like an h. 22.

One of the three tombstones at Tavistock was brought thither from a place not

very far off called Buckland Monachorum: it reads in Eoman capitals: —

DOBVNNI FABEI FIl[l?]i ENABARRI. This explains the only portion of the Ogmic

inscription still legible: -rnrr-^n-^ ///// ///// n aba r r 23. Cornwall. — A

stone on Worthyvale farm, in |

|

|

|

|

|

304 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. the neighbourhood of Camelford,

shows traces of an Ogmic inscription ending in 1 1 1 1 1 , i: the preceding

letter is rather doubtful, but it may be an r. The other inscription is in

debased- Eoman capitals with one or two Kymric letters intermixed, especially

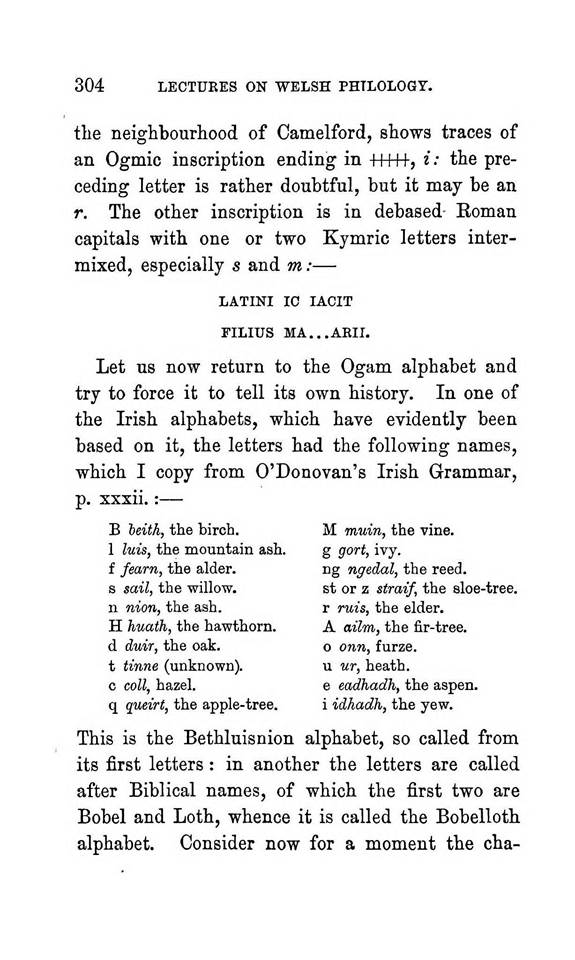

s and m: — LATINI 10 lACIT FILIUS MA...ABII, Let us now return to the Ogam

alphabet and try to force it to tell its own history. In one of the Irish

alphabets, which have evidently been based on it, the letters had the

following names, which I copy from O'Donovan's Irish Grammar, p. xxxii.: — B

ieith, the birch. M muin, the vine. 1 luis, the mountain ash. g gort, ivy. f

fearn, the alder. ng ngedal, the reed. s sail, the willow. st or z straif,

the sloe-tree. n nion, the ash. r ruis, the elder. H huath, the hawthorn. A

ailm, the fir-tree. d duir, the oak. o onn, furze. t tinne (unknown). u ur,

heath. c coll, hazel. e eadhadh, the aspen. q queirt, the apple-tree. i

idkadh, the yew. This is the Bethluisnion alphabet, so called from its first

letters: in another the letters are called after Biblical names, of which the

first two are Bobel and Loth, whence it is called the Bobelloth alphabet.

Consider now for a moment the cha- |

|

|

|

|

|

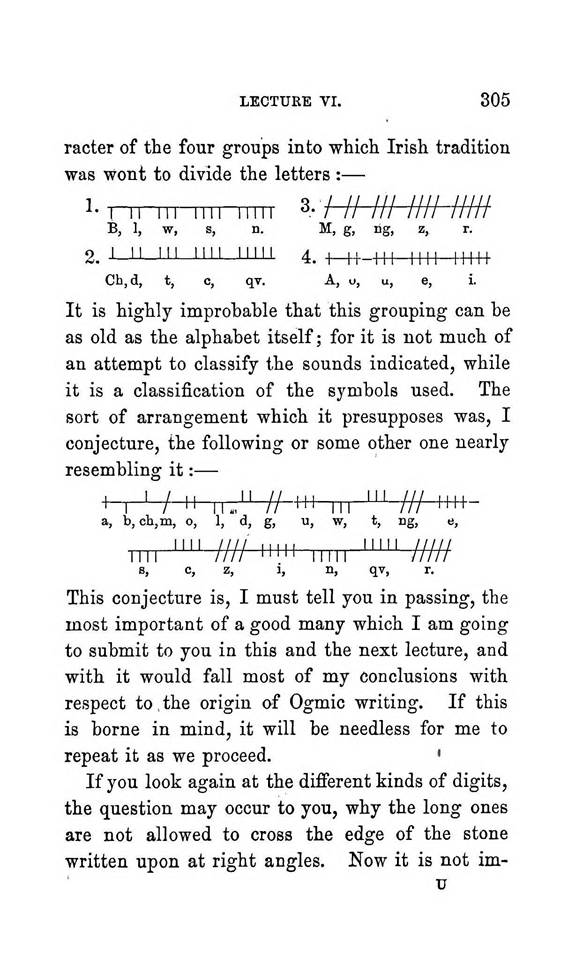

LECTURE VI. 305 racter of the four groups into which Irish

tradition was wont to divide the letters: — i- i II III nil m il 3, 7 // ///

//// m B, 1, w, s, n. M, g, lig, z, r. 2. I II III nil Hill 4. +^- 1 1 1 nil

I W+ Ch, d, t, o, qv. A, o, u, e, i. It is highly improbable that this

grouping can be as old as the alphabet itself; for it is not much of an

attempt to classify the sounds indicated, while it is a classification of the

symbols used. The sort of arrangement which it presupposes was, I conjecture,

the following or some other one nearly resembling it: — I I ' / II 11.,"

// III III ' " / / / UN - a, b, chjin, o, 1, d, g, u, w, t, Dg, e, MM

"" ////m i l m il '"" ///// s, c, z, I, n, qv, r. This

conjecture is, I must tell you in passing, the most important of a good many

which I am going to submit to you in this and the next lecture, and with it

would fall most of my conclusions with respect to , the origin of Ogmic

writing. If this is borne in mind, it will be needless for me to repeat it as

we proceed. ' If you look again at the different kinds of digits, the

question may occur to you, why the long ones are not allowed to cross the

edge of the stone written upon at right angles. Now it is not im- u |

|

|

|

|

|

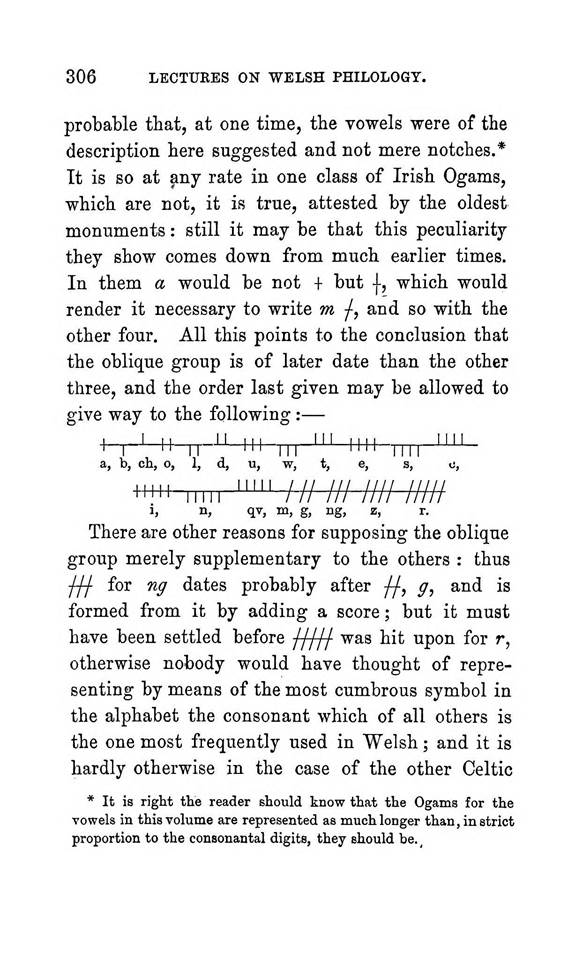

306 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY, probable that, at one time, tbe

vowels were of the description here suggested and not mere notches.* It is so

at ^ny rate in one class of Irish Ogams, which are not, it is true, attested

by the oldest monuments: still it may be that this peculiarity they show

comes down from much earlier times. In them a would be not + but |, which

would render it necessary to write m -f, and so with the other four. All this

points to the conclusion that the oblique group is of later date than the

other three, and the order last given may be allowed to give way to the

following: — I , 1 II ,11 I II ,,, III nil ,,,, nil ' I " II "I III

I'" III! a, b, ch, o, 1, d, u, w, t, e, s, o, m il Hil l '""

III III nil mil 1, n, qv, m, g, ng, z, r. There are other reasons for supposing

the oblique group merely supplementary to the others: thus /// for ng dates

probably after -f-j; g, and is formed from it by adding a score; but it must

have been settled before ///// was hit upon for r, otherwise nobody would

have thought of representing by means of the most cumbrous symbol in the

alphabet the consonant which of all others is the one most frequently used in

Welsh; and it is hardly otherwise in the case of the other Celtic * It is

right the reader should know that the Ogams for the vowels in this volume are

represented as much longer than, in strict proportion to the consonantal

digits, they should be.^ |

|

|

|

|

|

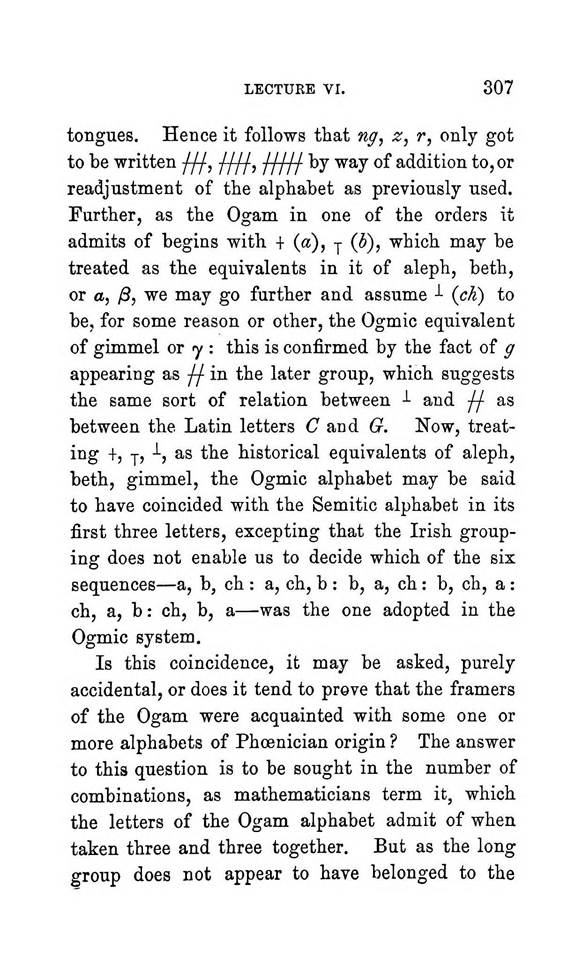

LECTURE VI. 307 tongues. Hence it follows that ng, z, r, only got

to be written j-j-j-, -j-fjj, ///// by way of addition to, or readjustment of

the alphabet as previously used. Further, as the Ogam in one of the orders it

admits of begins with + («), j (b), which may be treated as the equivalents

in it of aleph, beth, or a, /3, we may go further and assume -'- {ch) to be,

for some reason or other, the Ogmic equivalent of gimmel or y: this is

confirmed by the fact of g appearing as -fj- in the later group, which

suggests the same sort of relation between -•- and jj- as between the Latin

letters C and G. Now, treating +, ■]-, -•-, as the historical

equivalents of aleph, beth, gimmel, the Ogmic alphabet may be said to have coincided

with the Semitic alphabet in its first three letters, excepting that the

Irish grouping does not enable us to decide which of the six sequences — a,

b, ch: a, ch, b: b, a, ch: b, ch, a: ch, a, b: ch, b, a — was the one adopted

in the Ogmic system. Is this coincidence, it may be asked, purely accidental,

or does it tend to prove that the framers of the Ogam were acquainted with

some one or more alphabets of Phoenician origin? The answer to this question

is to be sought in the number of combinations, as mathematicians term it,

which the letters of the Ogam alphabet admit of when taken three and three

together. But as the long group does not appear to have belonged to the |

|

|

|

|

|

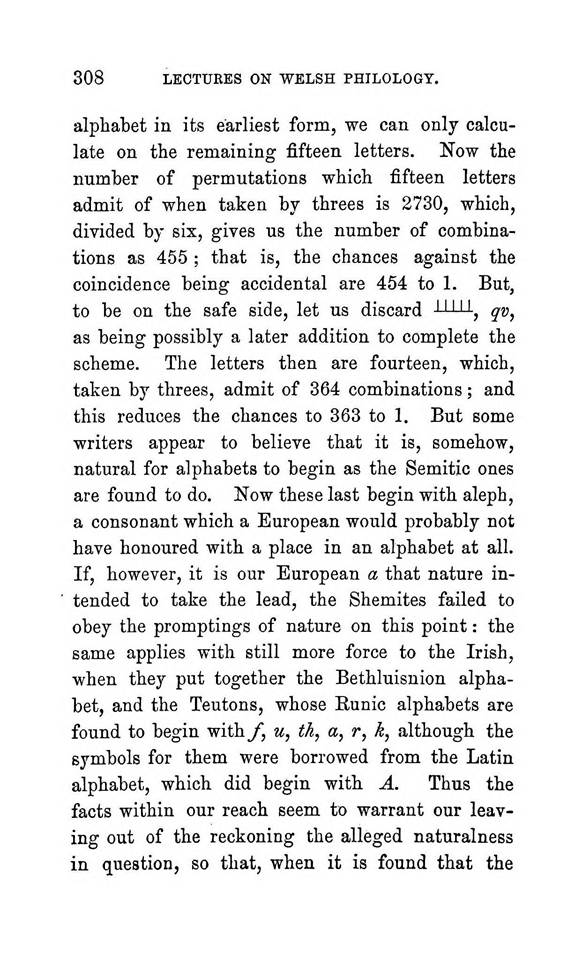

308 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. alphabet in its earliest form, we

can only calculate on the remaining fifteen letters. Now the number of

permutations which fifteen letters admit of when taken by threes is 2730,

which, divided by six, gives us the number of combinations as 455; that is,

the chances against the coincidence being accidental are 454 to 1. But, to be

on the safe side, let us discard -LU-Li, qn^ as being possibly a later

addition to complete the scheme. The letters then are fourteen, which, taken

by threes, admit of 364 combinations; and this reduces the chances to 363 to

1. But some writers appear to believe that it is, somehow, natural for

alphabets to begin as the Semitic ones are found to do. Now these last begin

with aleph, a consonant which a European would probably not have honoured

with a place in an alphabet at all. If, however, it is our European a that

nature intended to take the lead, the Shemites failed to obey the promptings

of nature on this point: the same applies with still more force to the Irish,

when they put together the Bethluisnion alphabet, and the Teutons, whose

Kunic alphabets are found to begin withy, m, th, a, r, k, although the

symbols for them were borrowed from the Latin alphabet, which did begin with

A. Thus the facts within our reach seem to warrant our leaving out of the reckoning

the alleged naturalness in question, so that, when it is found that the |

|

|

|

|

|

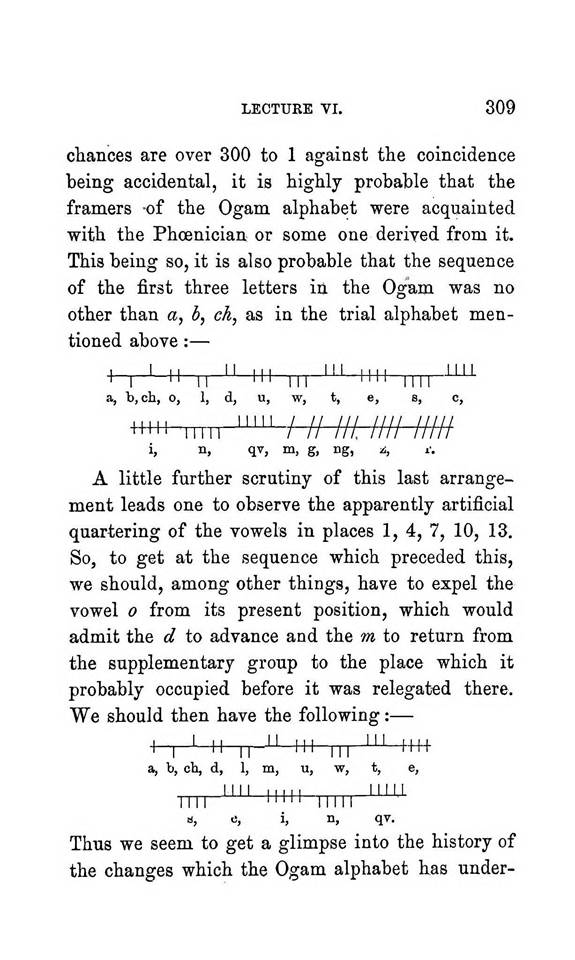

LECTURE VI. 309 chances are over 300 to 1 against the coincidence

being accidental, it is highly probable that the framers -of the Ogam alphabet

were acquainted with the Phoenician or some one deriyed from it. This being

so, it is also probable that the sequence of the first three letters in the

Ogam was no other than a, 6, ch, as in the trial alphabet mentioned above: —

I , I I I ,, II III ,,, III nil ,,,, Mil I I II II III III i"i nil a, b,

ch, 0, 1, d, u, w, t, e, s, c, M il l inn ' "" I II lli ll ll mil

i, n, qv, m, g, ng, ^ A little further scrutiny of this last arrangement

leads one to observe the apparently artificial quartering of the vowels in

places 1, 4, 7, 10, 13. So, to get at the sequence which preceded this, we

should, among other things, have to expel the vowel from its present

position, which would admit the d to advance and the m to return from the

supplementary group to the place which it probably occupied before it was

relegated there. We should then have the following: — I I " III III '

" ' I II a, b, ch, d, 1, m, u, w, t, e, I II iini II 1 1 III" II 1

1 1 a, e, i, n, qv. Thus we seem to get a glimpse into the history of the changes

which the Ogam alphabet has under- |

|

|

|

|

|

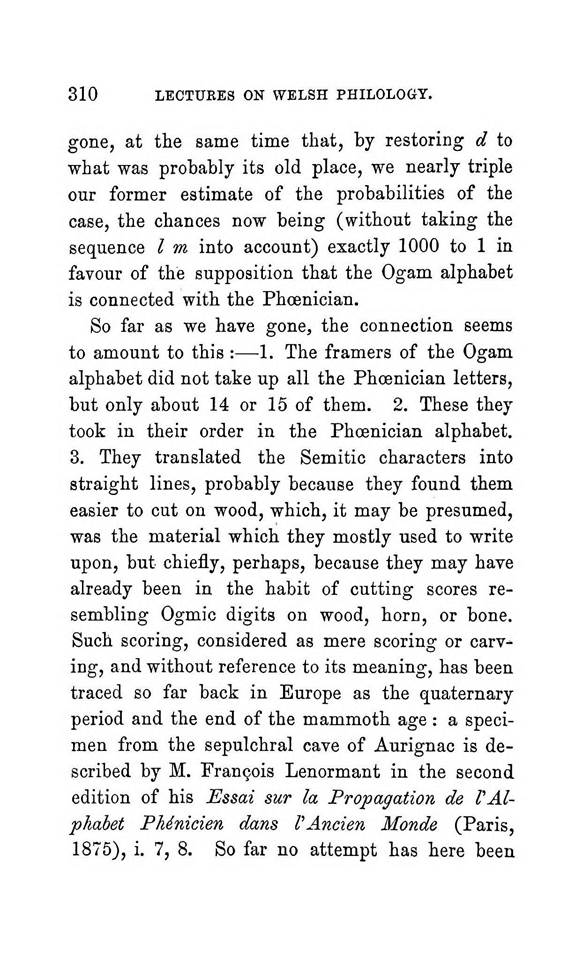

310 LECTUEES ON WELSH PHILOLOftT. gone, at the same time that, by

restoring d to what was probably its old place, we nearly triple our former

estimate of the probabilities of the case, the chances now being (without

taking the sequence I m into account) exactly 1000 to 1 in favour of the

supposition that the Ogam alphabet is connected with the Phoenician. So far

as we have gone, the connection seems to amount to this: — 1. The framers of

the Ogam alphabet did not take up all the Phoenician letters, but only about

14 or 15 of them. 2. These they took in their order in the Phoenician

alphabet. 3. They translated the Semitic characters into straight lines,

probably because they found them easier to cut on wood, which, it may be

presumed, was the material which they mostly used to write upon, but chiefly,

perhaps, because they may have already been in the habit of cutting scores

resembling Ogmic digits on wood, horn, or bone. Such scoring, considered as

mere scoring or carving, and without reference to its meaning, has been traced

so far back in Europe as the quaternary period and the end of the mammoth

age: a specimen from the sepulchral cave of Aurignac is described by M.

FranQois Lenormant in the second edition of his Essai sur la Propagation de V

Alphabet PMnicien dans VAncien Monde (Paris, 1875), i. 7, 8. So far no

attempt has here been |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 311 made to show with which of the Phoenician

alphabets, that is the Phoenician alphabet properly so called, or some one of

those of Greece or Italy which have been traced to it, the Ogam is connected.

History and geography do not encourage ■one to expect to find any

immediate connection between the Ogam and the alphabets of Greece: the

ordinary Roman alphabet hardly suits, as it has only the one symbol v for u

and?», not to mention other reasons which might be adduced: similarly we

might go on excluding the Etruscan and Runic alphabets. For the present,

then, we shall rest content with the bare fact, that the Ogam is in a manner derived

from the Phoenician alphabet, without proceeding to attempt to trace the

connection between them step by step. The rest of this lecture will,

accordingly, be devoted to a brief mention of some of the Goidelo-Kymric

traditions bearing on the origin of writing among the Celts. The allusions in

Irish literature to the Ogam are various and numerous, and a succinct account

of the grammatical treatises, which deal with it, will be found in the

following paragraph quoted from an abstract of a paper read before the Royal

Irish Academy in 1848 by Prof. Graves, now Bishop of Limerick: — " The

Book of Leinster, a MS. of the middle of the 12th century, contains |

|

|

|

|

|

312 LECTURE,S ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. a passage in which it [the key

to the Ogam] ia briefly given. The Book of Ballymote, written about the year

1370, contains an elaborate tract, which furnishes us with the keys to the

ordinary Ogham, and a vast variety of ciphers, all formed on the same

principle. The Book of Lecan (written in the year 1417) contains a copy of

the Uraicept, a grammatical tract, perhaps, as old as the 9th century, in

which are many passages relating to the Ogham alphabet, and all agreeing, as

regards the powers of the characters, with what is laid down in the treatise

on Oghams in the Book of Ballymote. Dr. O'Connor, indeed, speaks of a manuscript

book of Oghams written in the 11th century, and once in the possession of Sir

James Ware. Mr. Graves has ascertained that this is merely a fragment of the

above-mentioned Ogham tract. It is now preserved in the library of the

British Museum, and does not appear to have b,een written earlier than the

15th or 16 th century." Some valuable extracts from, and fac-similes of

the Ballymote tract have lately been published by Mr. G. M. Atkinson in the

Journal of the Kilkenny Archceological Society (vol. iii. pp. 202-236), to

which we shall have occasion to refer more than once. There, in answer to the

question, " By whom and from whence are the veins and beams in the Ogaim

tree named? " |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE TI. 313 we have the curious reply: — " Per alios. It

came from the school of Phenius, a man of Sidon, viz., schools of philosophy

under Phenius throughout the world, teaching the tongues (he thus employed),

in numher 25." But, to pass by the other traditions respecting this

early Fenian, we come to Ogma, who is said to have been the inventor of the

Ogam, and from whom it is called Ogam, also Ogum, and, in later Irish, Ogham

with a silent gh. Ogma is described as the son of Elathan of the race of the

Tuatha de Danann, whence it is clear that he is as mythical a personage as

Irish legend could well make him. And from his being called, as appears from

Mr. Atkinson's paper, Ogma the Sun-faced, it seems probable that he was of

solar origin. Ogma being much skilled in dialects and in poetry, it was he,

we are told, who invented the Ogam to provide signs for secret speech only

known to the learned, and designed to be kept from the vulgar and poor of the

nation. . For not only was a system of writing called Ogam, but also a

dialect, or mode of speech, bears that name. Of this O'MoUoy, cited in the

preface to O'Donovan's Irish Grammar, p. xlviii., says: " Obscurum

loquendi modum, vulgo Ogham, antiquariis Hiberniae satis notum, quo nimirum

loquebantur syllabizando voculas appellationibus litterarum, dipthongorum, et

triphthongorum ipsis dumtaxat notis." O'Dono- |

|

|

|

|

|

314 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. van further quotes an entry in

the Annals of Olonmacnoise to the following effect, as translated, in 1627,

by Connell Mageoghegan:— " a.d. 1328. Morish O'Gibelan, Master of art,

one exceeding well learned in the new and old laws, civille and cannon, a

cunning and skillfull philosopher, an excellent poet in Irish, an eloquent

and exact speaker of the speech, which in Irish is called Ogham, and one that

was well seen in many other good sciences: he was a canon and singer at

Twayme, Olfyn, Aghaconary, Killalye, Enaghdown, and Clonfert; he was official

and common judge of these dioceses; ended his life this year." To pass

by, for the present, the motive attributed to Ogma in his invention, we seem

to find him here in the character of the man of letters, and this is quite in

harmony with the only trace of his footsteps which has been discovered on

Kymric ground, namely, in the Welsh derivative ofydd, which probably stands

for an earlier omUS = ogmi^, and seems to have formerly meant a man of

science and letters; now it is defined to be an Eisteddfodic graduate who is

neither bard nor druid, and translated into ovate. Thus, perhaps, it would be

no overhasty generalising to infer that with the insular Celts Ogma's

province was language as literature, as the record of the past and the repository

of knowledge. The Gauls, on |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 315 the other hand, looked at their Ogmius, according

to Lucian's account, from the point of view of language as the means of

persuasion; for they represented him as an extremely old man drawing after

him a crowd of willing followers by means of tiny chains connecting their

ears with the tip of his tongue. Otherwise, be it observed, he seems to have

had the ordinary attributes of Hercules, whence it would seem that he, like

his Goidelic namesake, was of solar origin. It is probable, therefore, that

his influence over the crowds who rejoiced to follow him was in the first

instance due, not to his oratorical skill, the sweetness of his voice, or his

power of persuasion, but to the contents of his words, to the wisdom he had

to impart, and the wonderful experiences he could relate. . How could it be

otherwise in the case of one — to borrow the words applied in the Odyssey to

the sun — "^0? TravT e<j)opa km iravr eiraKovei? The Irish were

perhaps alone in attributing to him the origin of letters and the cultivation

of a dialect not understood by the people: at any rate Welsh tradition would

seem to point in quite another direction. But it is hardly necessary to state

that, owing to the Ogam having got out of use in the West of Britain as early

as the 8th or 9th century. |

|

|

|

|

|

316 LECTURES ON "WELSH PHILOLOGY. the allusions to it in

Welsh literature are exceedingly faint and nebulous. It may possibly be

proved that those about to be here mentioned do not in any way refer to the

Ogam; but the point I wish to insist upon is that they agree with Irish

tradition in placing the origin of writing — whether Ogmic or other — before

the Christian era. In the lolo MSS. (pp. 20'3-206), there are a few

paragraphs on the Welsh alphabet from manuscripts supposed to be traceable to

the possession of Llewelyn Sion, a Glamorganshire bard and collector of

antiquities, who died in the year 1616. Certainly there seems to be no reason

to think that they are, in the shape in which we find them, of an earlier

date; but that does not prove them not to contain a slender element of

ancient tradition beneath the incrustations of later times, and in spite of

their evident reference, in the first instance, to the bardic alphabet called

Coelbren y Beir.dd, which may be briefly characterised as the form the Eoman

alphabet took when carved on wood by the Welsh in the 15th century: see

Stephens's essay on the subject in the^rc^ Cambrensis for 1872, pp. 181-210.

One of these paragraphs runs thus: " In the time of Owain ap Maxen

Wledig the race of the Cymry recovered their privileges and crown: they took

to their original, mother-tongue instead of the Latin, which had well-nigh

overrun the Isle of Britain, |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 31 and in Welsh they kept the history, records, an

classifications of country and nation, restoring t memory the ancient

Oymraeg, their original wore and idioms. Owing, however, to their forgettin

and misunderstanding the old orthography of tl ten primary letters they fell

into error, and thi arose a disagreement as to [the spelling of] severs

ancient words." The writer goes on to give ir stances which show that

the latter part of tl passage is a mere corollary to the preceding par and

applicable to nothing earlier than the numeroi foibles of Welsh orthography

in the Middle Age Another of the paragraphs alluded to is to the fo lowing

effect: " Before the time of Beli the Gres ap Manogan there were but ten

letters, and the were called the ten awgrym, namely, a, p, c, ( t, i, 1, r,

0, s: afterwards m and n were discoverec and afterwards four others, so that

now being sij teen they were established with the publicity an sanction of

state and nation. After the coming ( the faith in Christ two other letters

were adde( namely, u and ^, and in the time of King Arthi there were fixed

twenty primary letters, as at pr( sent, by the advice of Taliesin Benbeirdd,

Urie Rheged's domestic bard. It was according \ the alphabet of the eighteen

that was arrange OIU, that is, the unutterable name of God: b< fore that

system it was 010 according to the si2

|

|

|

|

|

|

318 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. teen. Of principal awgrymau there

are not to the present day more than twenty letters or twenty awgrymy The

writer dwells on the repeated additions made to the alphabet, and the numbers

he gives at successive stages are 10, 12, 16, 18, 20, which are clearly not

all to be taken au pied de la lettre; for national sanction is not mentioned

by him till we come to the alphabet of 16; and to what Aryan alphabet could

10 and 12 apply? He has supplied us with the key to his blundering in the

word awgrym (now 'a hint or suggestion,' plural awgrymau), which is simply

the 0. English word awgrim, augrim, algrim, borrowed. Now the Craft of Algrim

was arithmetic (on the history of the word, see Max Miiller's Lectures^ ii.

p. 300, 301), and it is clear that he has set off his account of the alphabet

by a strange attempt to base it on the decimal system of numeration. It is

not to be forgotten that Llewelyn Sion had probably heard of the algebraists

and arithmeticians Vieta, Harriot, Wright, and Napier. Perhaps it is in the

same direction we should look for the explanation of the mystic 010. In

another version the arithmetical and alphabetical elements are kept somewhat

more apart, the former showing an inveterate tendency to secrecy, which is

not so evident in the |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 319 case of tlie latter: " la tine principal

times of the race of the Cymry the letters were called ystorrynau [supposed

to mean cuttings; but if cuttings, ^hj jaot fractions Pi: after the time of

Beli ap Manogan they were called letters, and before that there were only the

ten primary ystorryn, which had been a secret from everlasting with the bards

of the Isle of Britain for the preservation of record of country and nation.

But Beli the Great made them sixteen, and subject to that arrangement he made

them public, causing that thenceforth -there should never be secrecy with

regard to the knowledge of the letters, subject to the arrangement which he

had made touching them, while he left the ten ystorryn under secrecy. After

the coming of the faith in Christ the letters were made eighteen, and afterwards

twenty, and so they were retained to the time of Geraint Fardd Glas, who

fixed them at twenty-four." The next extract is from a document on

Bardism cited by Mr. D. Silvan Evans in Skene's Four Ancient Books of Wales

(ii, 324): he assigns it to the end of the 15th century, and gives references

which will here be utilised. The passage in point is not very lucid, but it

seems to mean this: " The three elemeiits of a letter are /|\, since it

is in the presence of one or other of the three |

|

|

|

|

|

320 LECTUKES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. a letter consists; they are three

beams of light, and it is of them are formed the sixteen ogyrvens, that is,

the sixteen letters. Belonging to another art also there are seven score and

seven ogyrvens, which are no other than the symbols of the seven score and

seven Welsh parent-words, whence every other word." The /|\ would be a

correct analysis of the letters of nations who habitually wrote on slips of

wood, as the nature of that material would compel one to avoid the use of

curves and horizontal lines: thus it would apply to Ogams and Eunes as well

as to the Coelbren y Beirdd, which the writer decidedly had in view. The

three beams of light was an after-thought, or a bit of another tradition; but

what mostly interests me in this extract is the word ogyrven. The sixteen

ogyrvens are evidently the same as the sixteen letters of the previous

extracts; but the seven score and seven seem to refer to some theory of

root-words, and their number was not, as might be expected, very definite;

for, to go still further back, in a passage in the Book of Taliessin, a

manuscript of the 14th century, they are given as exactly seven score (Skene,

ii. 132, 325):— "^eith vgein ogyruen , Yssyd yn awen" i.e., there

are in awen [muse, poetry] seven score

|

|

|

|

|

|

LECTUKE VI. 32 Ogyrvens. The two kinds of Ogyrvens woul seem to

match the Ogam alphabet and the Ogai dialect of Irish tradition, but what is

more remart able is that Ogyrven is the name of a person, an a person not a

whit less mythical than Ogmj He is variously called Ogyrven, Ogynven, Ogyrfai

and (with the prefixed g of late Welsh) Gogyrfai as in a popular rhyme

referring to bis daughte Gwenbwyfar, Arthur's wife: — " Gwenliwyfar f

erch Ogyrfan gawr, Drwg yn feohan, gwaetli yn fawr." Gwinevere, giant

Ogyrvan's daughter, Naughty young, more naughty after. He is better known in

Welsh poetry in connec tion witb Ceridwen, the lady who owned tl cauldron of

sciences (jpair gwybodau), and whos inspiring aid Welsh poets are still

supposed t invoke: thus in two of the poems in the Blac Book of Carmarthen, a

manuscript of the 12t century, we meet with a formula of invocation i which

she is called (Skene ii. 6, 6) Ogyrve amhad, which is supposed to mean "

Ogyrven offspring." They are also associated in severs poems in tbe Book

of Taliessin (Skene ii. 15' 156), and in one of the instances Ceridwen

cauldron is called Ogyrven's: — " Ban pan doeth o peir \ig[ When up the

Muses three Ogyrwen awen teir:" ) ' ( From Ogyrven's cauldron can X |

|

|

|

|

|

322 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGr. However, Mr. Silvan Evans

translates it " High when came from the cauldron the three awens of

Qogyrwen." The difference is immaterial here, as he calls attention to a

poem of Cynddelw's where Ceridwen and Ogyrven are associated by the poet — he

flourished in the 12th century — who calls himself a " bard of the bards

of Ogyruen," with, probably, the same meaning as though he had said

" of Ceridwen:" see the Mi/v. Arch, of Wales, p. 167 of Gee's

edition (Denbigh, 1870). To project this on the solar myth theory, Gwenhwyfar

and Ceridwen are dawn-goddesses, and their father Ogyrven must be the

personification of night and darkness; and this is confirmed by the etymology

of the word Ogyrven, which would have been in 0. . Welsh probably Ocrmen,

divisible into Ocr-men. The first element ocr seems to have been meant in the

Luxembourg Folio, where atrocia is" glossed arotrion, which appears to

be a clerical error for arocrion, if that indeed be not the correct reading.

Now, just as Welsh ac, oc, ' and, with,' stand with respect to such words as

Greek ayxa>, Latin angustus, German eng, so ocr, ogr, stand to the words

which Fick, in his dictionary^ (p. 9), derives from anghra, such as Zend

angra, ' evil,' anra, ' evil, bad: ' for a few parallels see the Eevtie

Celtique, |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 323 ii. 190, The other part occurs also in tynghedfen,

a word which is used as a synonym of the simpler tynghed, 'fate, destiny.*

The former was probably at one time meant to express the personification more

clearly than the latter, though it does so no longer. The men (mutated fen or

ven) in question can hardly be of a different origin from the English verb to

mean and its congeners, among which may be mentioned Greek fievos, Sanskrit

manas, ' courage, sense,' manyus, ' courage, zeal, anger, rage,' Zend mainyu,

' spirit, sky.' This last qualified by anra, ' evil, bad,' makes in the

nominative anro mainyus (Justi), ' the evil spirit par excellence, Ahriman,

or the devil of the Persians and the great adversary of Ormuzd.' Thus our

Ogyrven seems to be almost the literal counterpart of Ahriman, and might be

rendered the evil spirit: Ogyrwen, if not a mere phonetic variation, would be

he of the evil smile, while Ogyrfan shows the same element fan (for man) as

in Cadfan, on an early inscribed stone Catamanus. In both it is probably of

the same origin and meaning as the English word man, so that Ogyrfan would

have meant the evil man, and even now we call the devil y gwr drwg, ' the bad

man.' His attributes are, unfortunately, so weather-worn that Welsh

literature hardly enables us to make them out, which is, perhaps, partly |

|

|

|

|

|

324 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. due to His having been dethroned

by the devil of the Bible, and partly to his connection with Ceridwen and

Gwenhwyfar. But a clue to them appears to be oifered us in another form of

his name: in Gee's Myv. Arch, of Wales, p. 396, it is Ocurvran, that is in

later spelling Ogyrfran, which would mean the evil crow, and suggests a

community of origin with the Irish Badb: see Mr. Hennessy's article on the

latter in the Revue Celtique, i. 32-57. The Badb is described as having the

form of a crow and as a bird of ill omen, confounding armies, impelling to

slaughter, and revelling among the slain. This will serve as a provisional

key to the meaning of a reference to Ogyrven in one of the poems in the Black

Book already alluded to: the lines are very obscure and run thus (Skene, ii.

6): " Ry hait itaut. rycheidv y naut. rao caut gelin. Ey chedwis detyf.

ry chynis gretyw. rac llety w ogyrven.'' The meaning is by no means clear,

but " rac caut gelin^'' which cannot but mean " against the insult

of an enemy," suggests that its parallel in the following line, rac

lletyw ogyrven, must be "against a sinister fate," or something

nearly approaching it, as indicated by the adjective lletyw, now written

lleddf. Similarly we are enabled to guess what Cynddelw meant {Myv. Arch, of

Wales, p. 154) when he praises a certain

|

|

|

|

|

|

LECTUEB VI. 32 man as being " a hero of the valour of Ogyrfan,

gwron gnryd Ogyrfan, where Ogyrfan seems 1 mean war and slaughter, probably

personified. In support of this view of Ogyrfen, we hav( besides tynhedfen, a

third compound, namely Aei fen, which, as aer is battle, war, must mean

spirit or divinity concerned with war: it is, accorc ing to Dr. Davies's

Welsh-Latin Dictionary, foun used in the feminine and applied to the riv(

Dee, which need not surprise you, as the De Deva, probably means ' the

goddess,' and as tl river is still called in Welsh Dyfrdroy, ' the wat( of

the divinity: ' Giraldus calls it Deverdoeu, tl full spelling of which would

now be Dyfrdwyw i Dyfrdroyf, whereby he upsets the popular et; mology, which

explains the word as meaning tl water of two {rivers). On river-names of th

class see M. Pictet's paper in the Revue Celtiqu ii. 1-9. However, the word

occurs also in tl sense of war or battle generally, as in Englynion Gdrugiau

{lolo MSS. 263), where we read: — " Goruc Arthen ap Arth Hen Rhag ffwyr

esgar ac asgen, Llafn ynghad ynghadr aerfen; " i.e., Arthur ap Arth Hen

against foeman's attai and injury made the blade (for use) in battle, stout

war. But why should the origin of letters have bei |

|

|

|

|

|

326 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. connected with Ogyrven, whose

character was from the first that of a dark and concealing heing? One might

answer that it was for the same reason which made the Irish attribute the

motive of secrecy to Ogma, though that ill agreed with his solar origin: both

versions, it may be, merely reflect the feeling with which the ignorant many

would regard the language, whether written or spoken, of the learned few. On

them the impression of mystery and awe produced by the sight of certain

characters cut on wood may easily be conceived to have led them to call them

the un\gogyrven ar bymtheg, that is, as though we called them ' the sixteen

devils.' Later, however, a solar patch was, so to say, sometimes sewn on the

tradition, in the shape of a reference to the three sunbeams /|\, which still

hold their place as a sacred symbol or talisman at the head ' of Eisteddfodic

announcements. But perhaps the question as to the relation in which Ogyrven

stood to letters is best disposed of by asking another, namely. How it is

that there exist even now people who think that knowledge and science are of

the devil? In former times this was, no doubt, very much more commonly the

case than it is now. The cryptic view taken of writing by the ignorant, and

incorporated in the Irish tradition touch-

|

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VI. 32 ing the Ogam, has sometimes led Irish archaeolc

gists into the error of thinking that the Ogam wa really a cryptic

contrivance. It is true that in i1 last days it may have fallen into the

hands ( pedants, but it still remains to be shown that eve a single Ogmio

monument of respectable antiquit in Ireland can in any sense whatever be said

to I of a cryptic nature. It is, of course, but naturs that writers, who have

no wish or no time to stud the laws of phonetic decay, should find in earl

Irish names merely disguised forms of the: modern continuators. Their view is

also suppose to derive support from a passage in Comae's Gloi sary, which

explains the Irish word fd as " wooden rod '• used by the Gael for

measurin corpses and graves, and this rod was," we ai told, "

always in the burial-places of the heather and to take it in his hand was a

horror to ever one, and whatever was abominable (adetche) f them, they used

to put in ogham upon it {^i6ke&' Three Irish Glossaries, p. Iv.). Here it

ha been supposed that we have an allusion to cryptic fashion of recording the

sins of a decease person; but it is difficult to see anything crypti in the

whole proceeding, unless it be the act ( leaving the/"^ in the

burial-place, which, in thE case, may have been meant to suggest, in a del; |

|

|

|

|

|

328 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. cate manner implying no ignoring

of tlie faults and shortcomings of the departed, that thenceforth his name

would have the full benefit of the maxim: " De mortuis nil nisi

bonum." ( 329 ) |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VII. " Nous nous sommes efforcfi jnsqu'3. present de

reconstituer les etapes successives qui couduisirent depuis la premidre

origiue de I'art d'6crire jusqu'^ rinvention dSfiuitlTe de I'alphabet. Nous

avons vu combien cette graude et f6conde inTention, qui aiuena recriture a

son dernier degre de perfection et en fit un instrument completement digne de

la pensee humaine, fut lente El se produire, combien p^ni- blement elle se

dggagea, par une marche graduelle, de I'ideograpbisme originaire. Nous avons

vu comment pour y parvenir il avait fallu la combinaison des efforts

successifs et des gSnies varies d'un peuple philosopbe, les Egvptiens, qui

sut con9evoir la decomposition de la syllabe et de I'abstraction de la

consonne, puis d'un peuple pratique et marchand, les Pheniciens, qui rejeta

tout Element id€ographique et reduisit le phonetisme, demeur6 seul, k

I'emploi d'une figure unique pour representor chaque articulation. Mais aussi

cette invention, qui demeurera I'etemelle gloire des fils de Chanaan, ne fut

faite qu' une seul fois dans le monde et sur un seul point de carte, et, une

fois accomplie, elle rayonna partout de proche en proche." — Pbakjois

Lenoemant. This lecture will be devoted mainly to conjectures, and tlie facts

adduced, it may as well be admitted at the outset, will be few and far

between. Of the latter, the principal one is the Phoenician alphabet, for

which, however, we have to use the Hebrew version, as giving us the order of

the letters, and also their names in a form which cannot be materially

different from that which they had in Phoenician. The other leading fact is

the Ogam system as attested by the oldest monuments extant in Wales and

Ireland. Given |

|

|

|

|

|

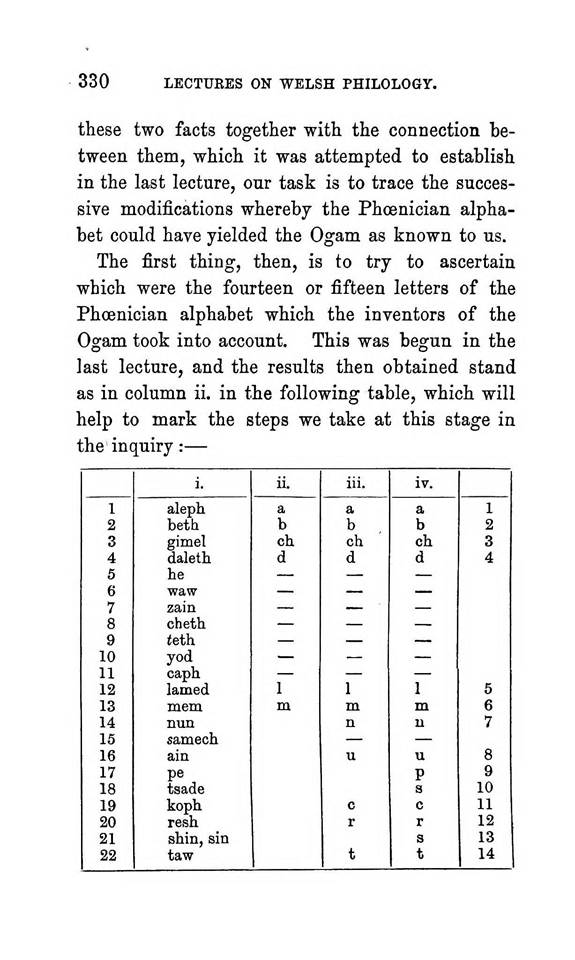

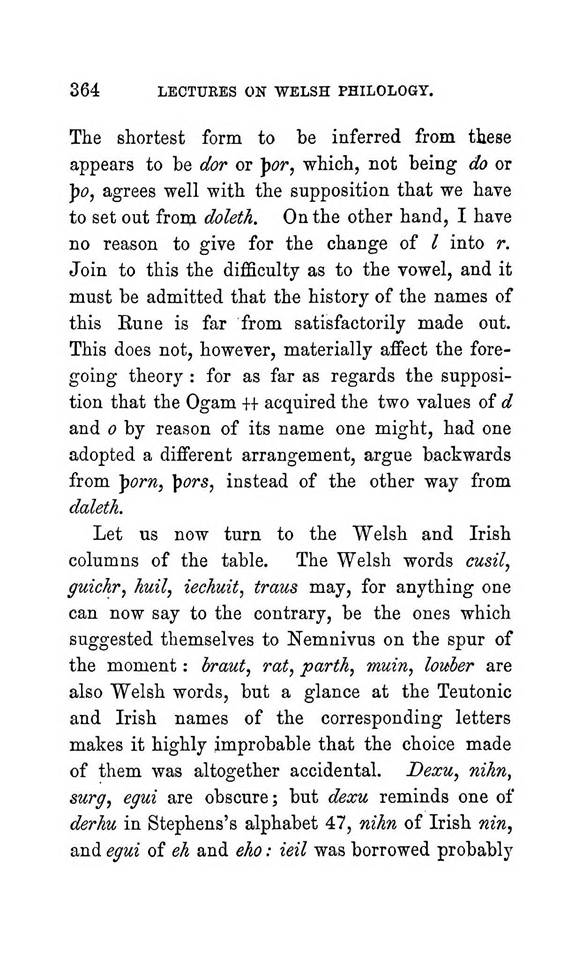

1 2 aleph beth a b a b a b

1 2 3 4 gimel daleth ch d ch d

oh d 3 4 5 he — — —

6 waw — — — 7 zain — — — 8 cheth — — — 9 ieth — — — 10 11 12 yod caph lamed 1

1 1 5 13

mem m m m 6 14 nun

n u 7 15 saxaech

— — 16 ain u u

8 17 18 pe tsade P s

9 10 19 20 koph resh c r

r 11 12 21 shin, sin s

13 22 taw t t

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

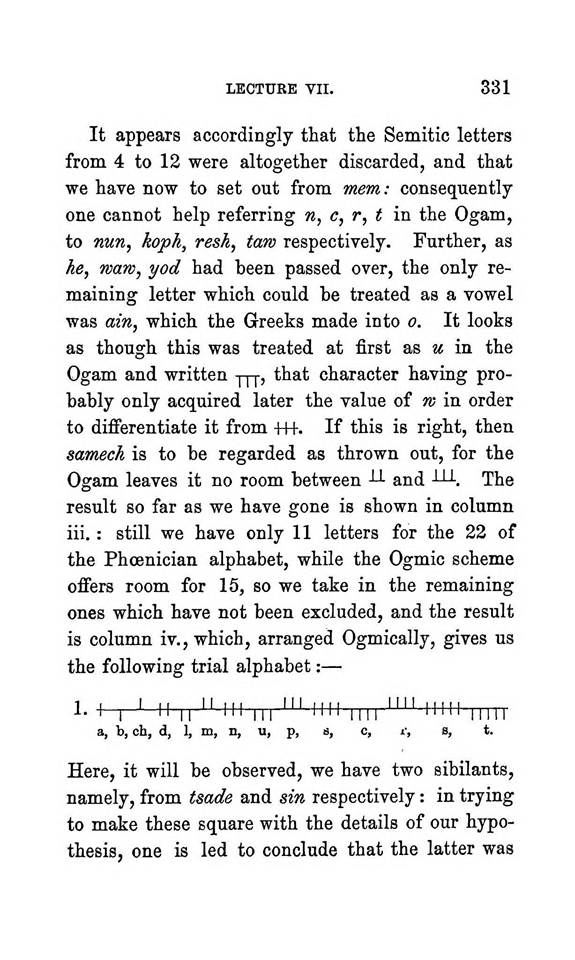

LECTURE VII. 331 It appears accordingly that the Semitic letters

from 4 to 12 were altogether discarded, and that we have now to set out from mem:

consequently one cannot help referring n, c, r, t in the Ogam, to nun, koph,

resh, taw respectively. Further, as he, maw, yod had been passed over, the

only remaining letter which could be treated as a vowel was ain, which the

Greeks made into o. It looks as though this was treated at first as u in the

Ogam and written -|-[-j-, that character having probably only acquired later

the value of w in order to differentiate it from +++• If this is right, then

samech is to be regarded as thrown out, for the Ogam leaves it no room

between ^ and -'-'-'■. The result so far as we have gone is shown in

column iii.: still we have only 11 letters for the 22 of the Phoenician

alphabet, while the Ogmic scheme offers room for 15, so we take in the

remaining ones which have not been excluded, and the result is column iv.,

which, arranged Ogmically, gives us the following trial alphabet: — 1- I I '

II II " III III '" 'III nil "" mil mi l a, b, ch, d, 1,

m, n, u, p, s, c, i, B, t. Here, it will be observed, we have two sibilants,

namely, from tsade and sin respectively: in trying to make these square with

the details of our hypothesis, one is led to conclude that the latter

was |

|

|

|

|

|

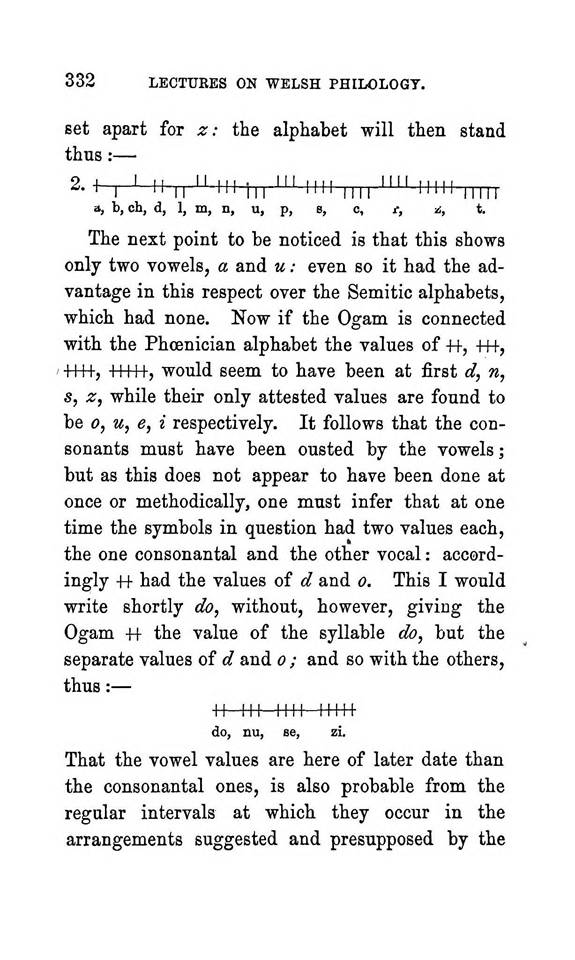

332 LECTUEES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. set apart for z: the alphabet

will then stand thus: — 2- 1 I ' 'h i " i iii ii ' " i i iii ii i

""in i ii iiii a, b, oh, d, 1, m, n, u, p, B, c, t, i, t. The next

point to be noticed is that this shows only two vowels, a and w; even so it

had the advantage in this respect over the Semitic alphabets, which had none.

Now if the Ogam is connected with the Phoenician alphabet the values of ff ,

+++, ' WW, +++++, would seem to have been at first d, n, s, z, while their

only attested values are found to be 0, u, e, i respectively. It follows that

the consonants must have been ousted by the vowels; but as this does not

appear to have been done at once or methodically, one must infer that at one

time the symbols in question had two values each, the one consonantal and the

other vocal: accordingly -H- had the values of d and o. This I would write

shortly do, without, however, giving the Ogam +1 the value of the syllable

do, but the separate values of d and o; and so with the others, thus: — I I I

I I ni l mil do, nu. Be, zi. That the vowel values are here of later date

than the consonantal ones, is also probable from the regular intervals at

which they occur in the arrangements suggested and presupposed by the |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VII. 333 grouping of the Irisli Ogam, wliich has already

been referred to in connection with its leading letters b, h, m, a, and the

permutations they admit of. But how did the vowels get into these positions,

and how were the consonants dislodged? We seem to have a clue to the answer

in the case of nu, which one cannot help regarding as suggested by the

letter-name nun: similarly zi, for si, is to be referred to the name sin. The

case of ++, do, looks as if the spelling daletk of the Hebrew name of the

fourth letter did not exactly give the pronunciation, which the first Ogmists

learned to give the word as they heard it. Was the latter more nearly doleth,

which approaches, I am told, the Arabic pronunciation of the word as used for

the letter and for door at the present day, or are we to assume rather that

they translated the word into their own language, that is into an Aryan

equivalent beginning with do, such as would, for instance, be Welsh dor, and

drws (for dams'), Irish dorus, all with dor for dvor, 0. English dor, ' door

'? Lastly, the vowel e was probably associated at first with the name pe or

resk; but sooner or later the analogy of +, ++, +++, f|-l4+, would naturally

lead to the use of fH-F or se with the values of s and e, and perhaps even to

the modification of its name into a form more nearly approaching sede than

tsade. Of course, if one could |

|

|

|

|

|

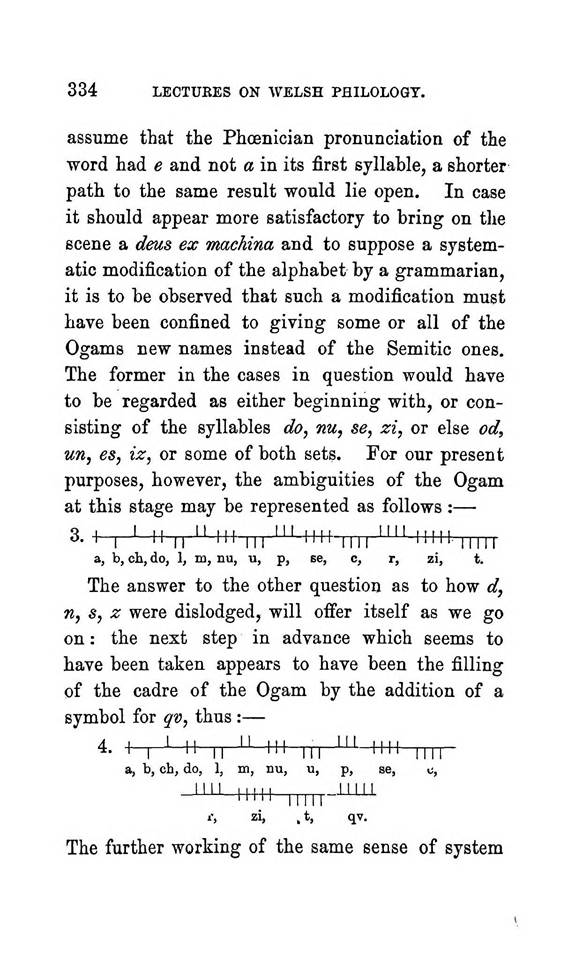

334 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. assume that the Phoenician

pronunciation of the word had e and not a in its first syllable, a shorter

path to the same result would lie open. In case it should appear more

satisfactory to bring on the scene a deas ex Tnachina and to suppose a

systematic modification of the alphabet by a grammarian, it is to be observed

that such a modification must have been confined to giving some or all of the

Ogams new names instead of the Semitic ones. The former in the cases in

question would have to be regarded as either beginning with, or consisting of

the syllables do, nu, se, zi, or else od, un, es, iz, or some of both sets.

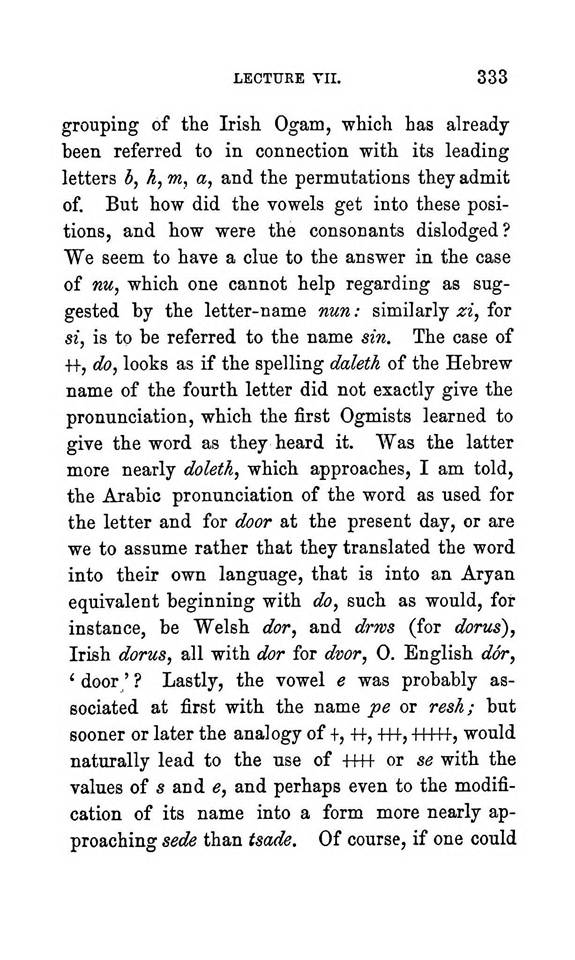

For our present purposes, however, the ambiguities of the Ogam at this stage

may be represented as follows: — 3- I I ' I I II " III II I ' I I

"" IIHIll l l l a, b, ch, do, 1, m, nu, u, p, Be, c, r, zi, t. The

answer to the other question as to how d, n, s, z were dislodged, will offer

itself as we go on: the next step in advance which seems to have been taken

appears to have been the filling of the cadre of the Ogam by the addition of

a symbol for qv, thus: — 4. I I ' I I II I ' I I I I I I III nil n i l a, b,

oh, do, 1, m, nu, u, p, se, c, "" II i i r -^ I-, Zl, .t, qv. The

further working of the same sense of system

|

|

|

|

|

|

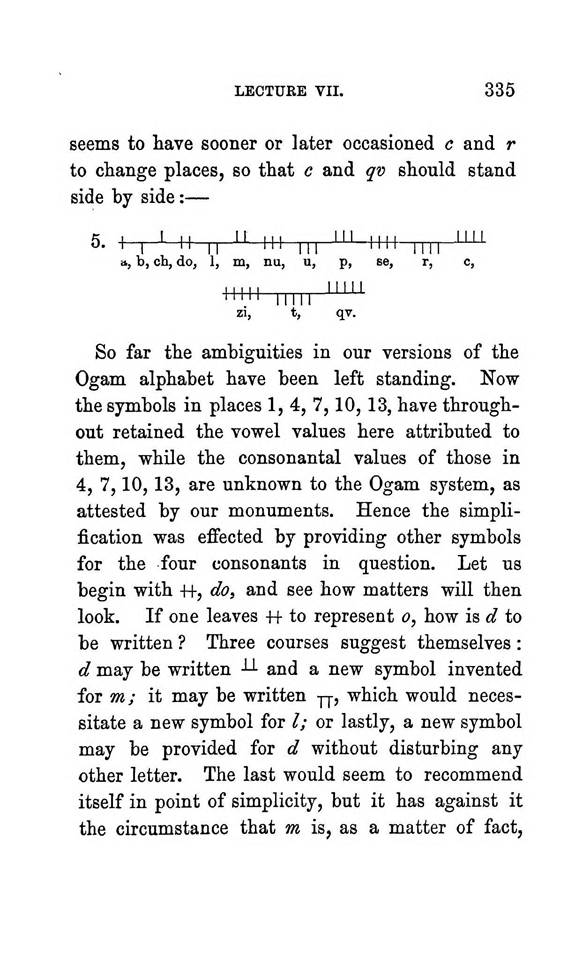

LECTURE VII. 335 seems to have sooner or later occasioned c and r

to change places, so that c and qv should stand side by side: — f\ 1 I I I II

III III 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0. 1 I -" II II " 111 111 iiii nil a, b,

ch, do, 1, m, nu, u, p, se, r, c,

"" IIII! zi, t, qv.

So far the ambiguities in our versions of the Ogam alphabet have been

left standing. Now the symbols in places 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, have throughout

retained the vowel values here attributed to them, while the consonantal

values of those in 4, 7, 10, 13, are unknown to the Ogam system, as attested

by our monuments. Hence the simplification was effected by providing other

symbols for the four consonants in question. Let us begin with ++, do, and

see how matters will then look. If one leaves ++ to represent o, how is d to

be written? Three courses suggest themselves: d may be written ^ and a new

symbol invented for m; it may be written jj-, which would necessitate a new

symbol for I; or lastly, a new symbol may be provided for d without

disturbing any other letter. The last would seem to recommend itself in point

of simplicity, but it has against it the circumstance that m is, as a matter

of fact. |

|

|

|

|

|

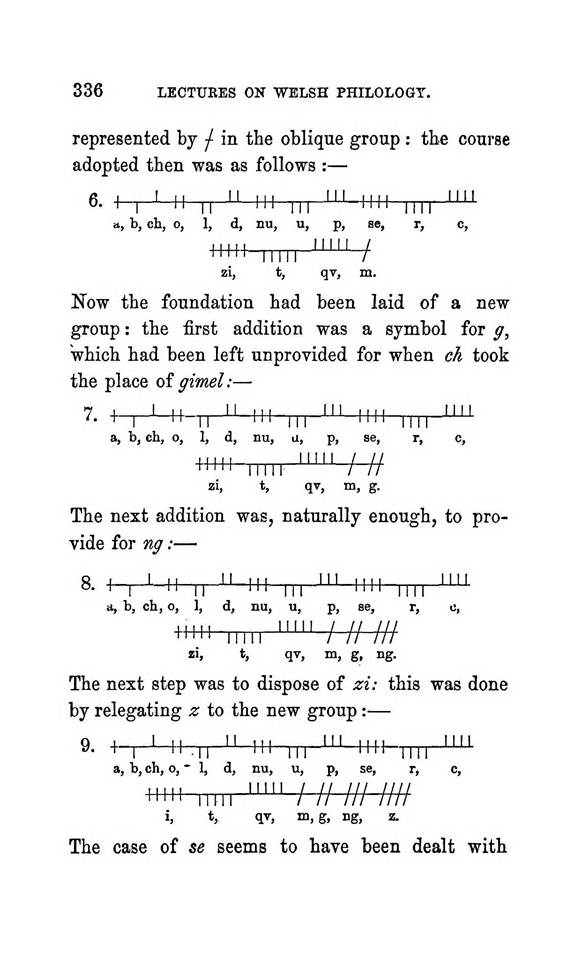

336 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. represented by / in the oblique

group: the course adopted then was as follows: — 6-^1 ' II II " Ml II I

'" I'll n il "" a, b, ch, 0, 1, d, nu, u, p, Be, r, c, ^^ m il

' "" / zi, t, qv, m. Now the foundation had been laid of a new

group: the first addition was a symbol for g, "which had been left

unprovided for when ch took the place oi gimel: — 7 I , I II ,. II III ...

Ill nil Mil /. I I ' II II III III III! MM a, b, ch, 0, 1, d, nu, a, p, se,

r, c, + 11 1 ' IIMI - ' "" /// ZI, t, qv, m, g. The next addition

was, naturally enough, to provide for ng: — 8- I I ' II II " III III

'" I 'll MM "" a, b, ch, o, 1, d, nu, u, p, se, r, c, + IIII

mi l '"" ////// zi, t, qv, m, g, ng. The next step was to dispose

of zi: this was done by relegating z to the new group: — Q I I I I M ,1 1 m

MM mi y. +■■ I II .11 III 111-'" iin-im a, b, oh, o, - 1, d,

nu, u, p, se, r, c, 'I'll mil '"" ////////// i, t> qT, m,g, ng,

z. The case of se seems to have been dealt with |

|

|

|

|

|

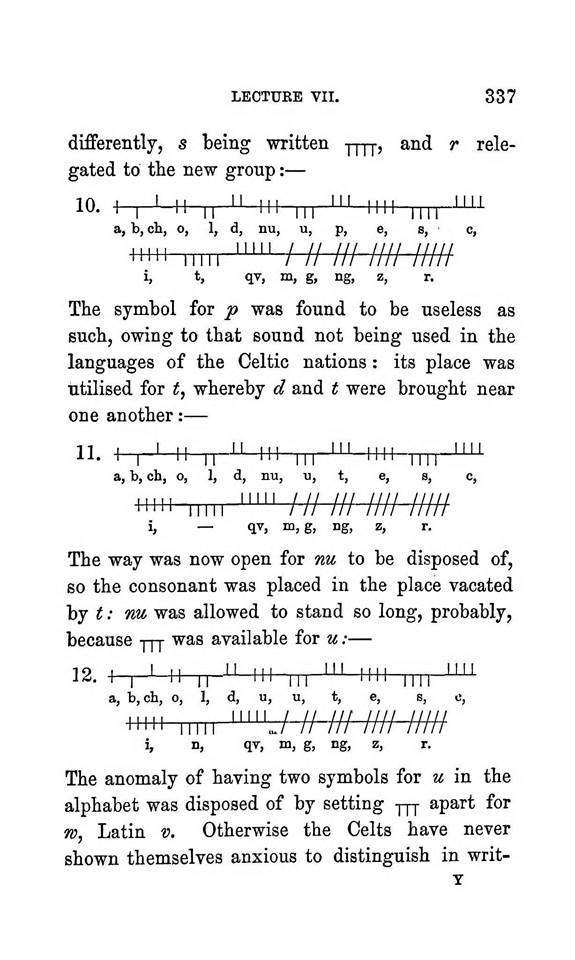

LECTURE VII. 337 differently, s being written jjjj, and r

relegated to the new group: — 10. I I ' II II 11 111 I II I I ' M i l ,111

nii a, b, ch, o, 1, d, nu, u, p, e, s, ■ c, mil iii i i '"" I

II III nil Hill 1, t, qv, m, g, ng, z, r. The symbol for p was found to be

useless as such, owing to that sound not being used in the languages of the

Celtic nations: its place was utilised for t, whereby d and t were brought

near one another: — n. I I I II II II III I II II I M i l 11 ,1 I'll a, b,

ch, o, 1, d, nu, u, t, e, s, o, mil M ill ' "" III III nil IIIII i,

— qv, m, g, ng, z, r. The way was now open for nu to be disposed of, so the

consonant was placed in the place vacated by t: nu was allowed to stand so

long, probably, because -j-p]- was available for u: — J2. I I I M ,1 "

III 1,1 "I MM 11,1 "" a, b,cli, 0, 1, d, u, u, t, e, s, o, m

il M i l l ' ^ ^ ^' J -H- lll nil IIIII i, n, qr, m, g, ng, z, r. The anomaly

of having two symbols for u in the alphabet was disposed of by setting jjj

apart for m, Latin v. Otherwise the Celts have never shown themselves anxious

to distinguish in writ- T |

|

|

|

|

|

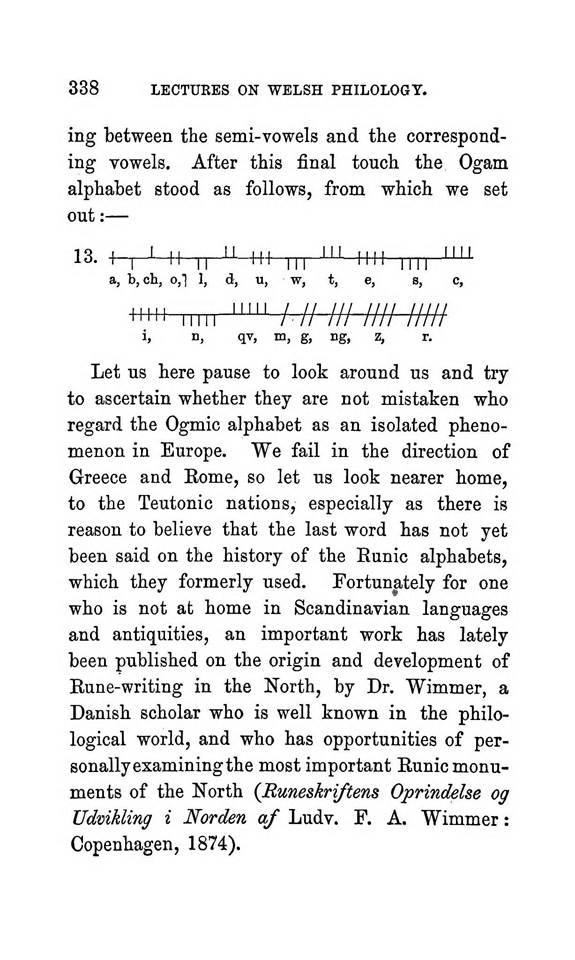

338 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. ing between the semi-vowels and

the corresponding vowels. After this final touch the Ogam alphabet stood as

follows, from which we set out: — 13. +-H-^f-Tr^^4 l II I I N Mil nil i l M

a, b, oh, 0,1 1, d, u, w, t, e, s, c, mil mil ' "" hll HI nil mil

1, n, qv, m, g, Dg, z, r. Let US here pause to look around us and try to ascertain

whether they are not mistaken who regard the Ogmic alphabet as an isolated

phenomenon in Europe. We fail in the direction of Greece and Eome, so let us

look nearer home, to the Teutonic nations, especially as there is reason to

believe that the last word has not yet been said on the history of the Eunic

alphabets, which they formerly used. Fortunately for one who is not at home

in Scandinavian languages and antiquities, an important work has lately been

published on the origin and development of Kune-writing in the North, by Dr.

Wimmer, a Danish scholar who is well known in the philological world, and who

has opportunities of personally examining the most important Eunic monuments

of the North (JRuneskriftens Oprindelse og Udvikling i Norden of Ludv. F. A.

Wimmer: Copenhagen, 1874). |

|

|

|

|

|

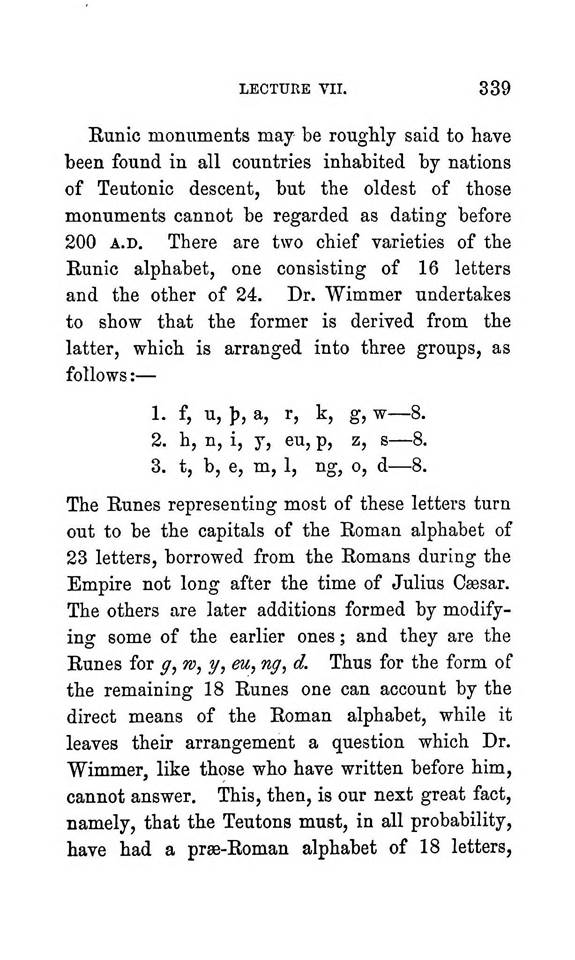

LECTURE VII. 339 Kunic monuments may be roughly said to have been

found in all countries inhabited by nations of Teutonic descent, but the

oldest of those monuments cannot be regarded as dating before 200 A.D. There

are two chief varieties of the Runic alphabet, one consisting of 16 letters

and the other of 24. Dr. Wimmer undertakes to show that the former is derived

from the latter, which is arranged into three groups, as follows: — 1. f, u,

Ip, a, r, k, g, w — 8. 2. h, n, i, y, eu, p, z, s — 8. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, ng,

o, d — 8. The Eunes representing most of these letters turn out to be the

capitals of the Roman alphabet of 23 letters, borrowed from the Romans during

the Empire not long after the time of Julius Osesar. The others are later

additions formed by modifying some of the earlier ones; and they are the

Runes for y, w, y, eu, ng, d. Thus for the form of the remaining 18 Runes one

can account by the direct means of the Roman alphabet, while it leaves their

arrangement a question which Dr. Wimmer, like those who have written before

him, cannot answer. This, then, is our next great fact, namely, that the

Teutons must, in all probability, have had a prae-Roman alphabet of 18

letters, |

|

|

|

|

|

340 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. which at the time when they were

induced to adopt the Eoman characters instead of their own stood as follows:

— 1. f, u, p, a, r, k — 6. 2. h, n, i, p, z, s — 6. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, o — 6.

The fact of the Eunic alphabet or the Futhark, as it is called from its first

letters, being from the first arranged into groups, appears to be a distinct

indication that it is the outcome of some such a system of writing as the

Ogam. So I venture to proceed to show how it can be connected with the

alphabet which has served as a key to the history of the changes which the

Ogam may have undergone at the hands of the Celts. But before beginning to do

so, it is to be noticed that the Celtic 6, cA, d have to be translated

into_/, h, J) in order to comply with the usual way of transcribing the

Futhark: and for its earlier history the change here implied is very little

more than this, as will be made clear later. Our first three alphabets as

given in the foregoing series will accordingly stand thus: — i.

+-T-i-H-n-^w-TTT-^-tw-rrrr ^^ i ' ' 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 a, f, h, Jj, 1, m, n, u, p,

s, k, r, a, t. a, f, h, J), 1, m, n, u, p, s, k, r, z, t. |

|

|

|

|

|

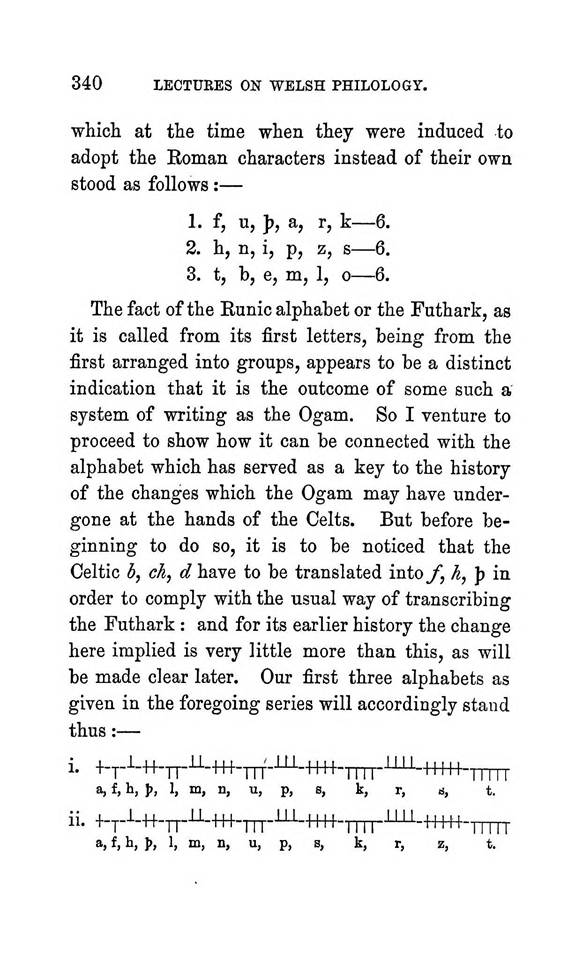

LECTURE VII. 341 iii. +.^-L++.^-il.+++.^ill.^+.^.iiil.+^.^^^ a>

f, ^, fo. 1. m, nu, u, p, se, k, r, zi, t. The systematising tendency

confined the vowels to one kind of characters, and -p|-|ceased to be used for

u:— iv. +-T-L++-^-li-+f|-^-iii.+^.^.lLU.+^^.^^ a, f,li,]jo, 1, m, nu, — , p,

se, k, r, zi, t. This allowed r to move one place forward and to enter

another class: — ■ V. +-^i-++-^ii-+H-^-Li^-++++-TnT-^-+++++-nm a, f, h,

j)o, 1, m, nu, r, p, se, k, — , zi, t. Now it was possible to separate the

two values of ■mn thus: — vi. +-^i-^-^-ii-+++-^-iii-+^-^-iiii-++m-ymT

a, f > ^, Jjo, 1, m, h", '•> p. se, k, z, i, t. The next step

seems to have been the invention of a new symbol for t: let us suppose it to have

been an oblique score: — vii. i-pl-ii-^li-ni-pp^-LU1 1 1 1 ,1 1 1 -Ull.fH^.y!

a, f , h, Jio, 1, m, nu, r, p, se, k, z, i, t. This naturally became the

commencement of a new group: the fitst addition was a character for 6, which

had previously been expressed by the same means asy.— viii. I I ' II II

" IH"||| '" III! a, f, h, yo, 1, m, nu, r, p, se, nil

"" mil /// k, z, 1, t, b. |

|

|

|

|

|

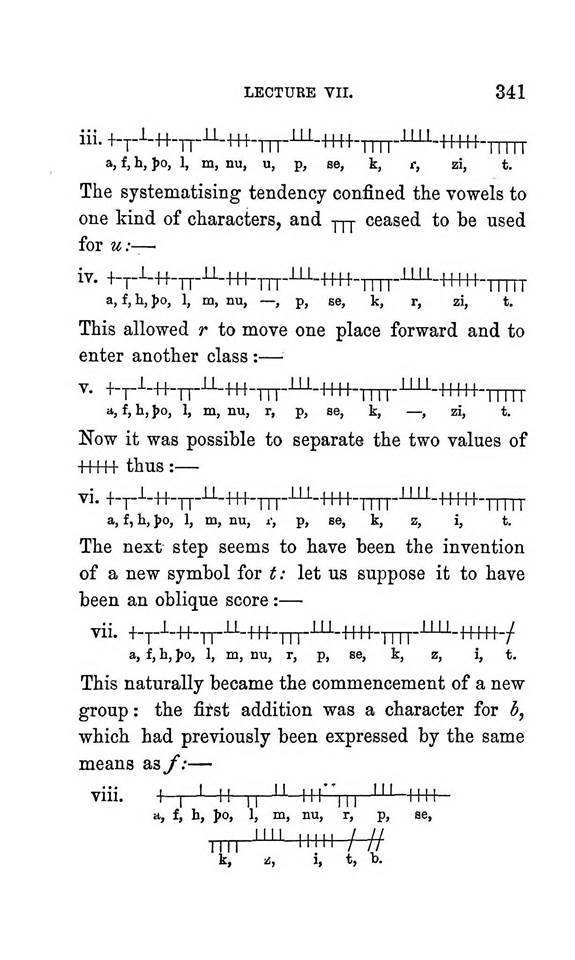

342 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. The next step taken seems to have

been to separate the values of ])<?. This was done by writing Jj either jj

or ^, and that hesitation rendered it necessary to have new symbols for I and

m: — ix. I I I II II II III III I" nil a, f, h, o, J>, }), nu, r, p,

se, nTT-^-+4+H^ // /// //// k, z, i, t, b, m, 1. Why m should precede I in

the new group I cannot say, and it should be borne in mind that the Runic

alphabets are by no means uniform as to the sequence of m and I: Dr. Wimmer

(pp. 190-196) thinks, it is true, that the sequence was at first invariably m

I, but I am not quite convinced by his reasoning that that o{ I m may not be

equally old. Eventually ^ ceased to be used for J), and became available for

the consonantal power of nu: — X. + I I II II II III II I III nil a, f, h, o,

J), n, u, r, p, se, n i l ' " 1 1 II nil mil k, z, 1, t, b, m, 1. Now a

new symbol was invented for s, which should stand by the side of that for the

nearly-related sound of z: — xi. I I I I I II II I ll -Ill II I I II! 1, f,

t, 0, J), n, u, r, p, e, Ti ll " " mi l ' "" //////.////

k, z, i, B, t, b, m, 1. Here we have an alphabet, which I would call a |

|

|

|

|

|

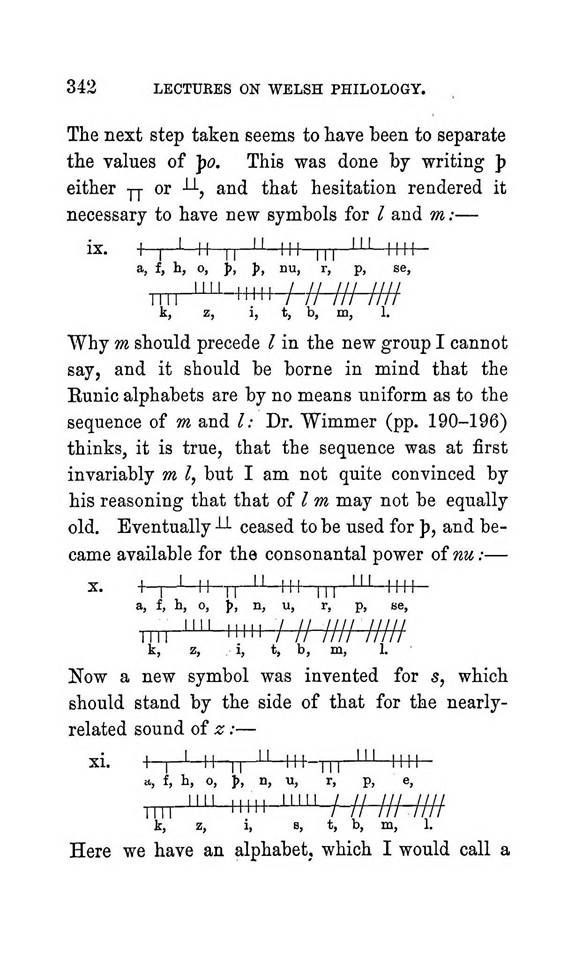

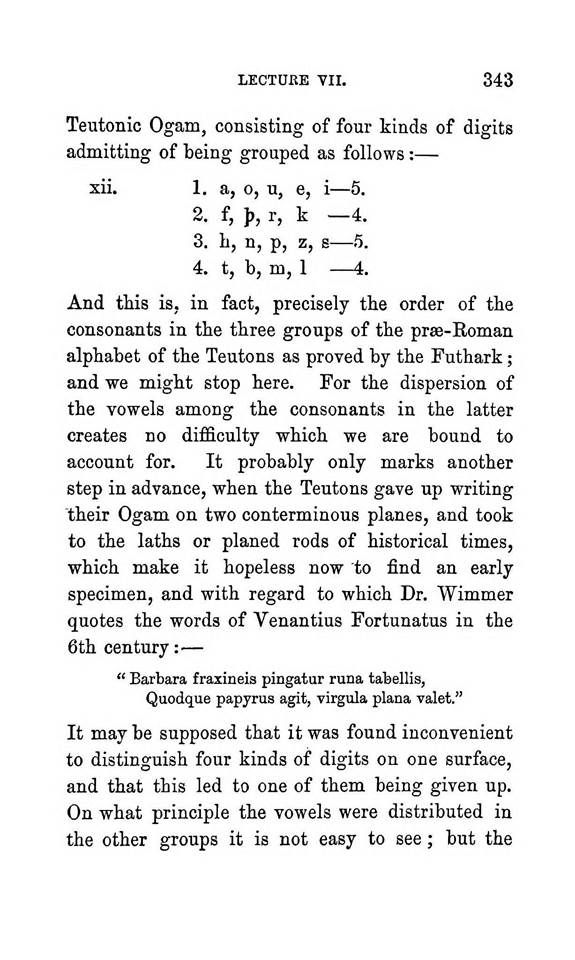

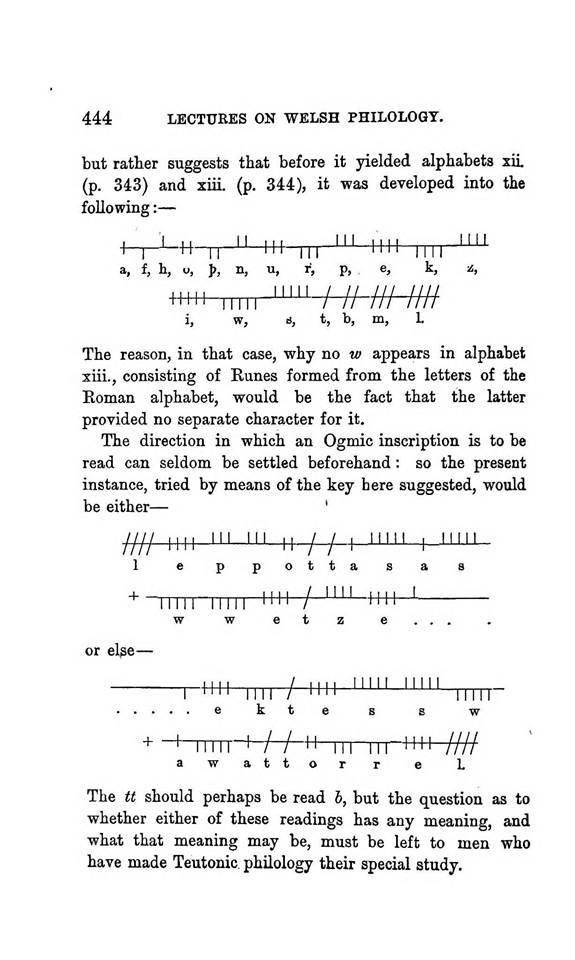

LECTUBE VII. 343 Teutonic Ogam, consisting of four kinds of digits

admitting of being grouped as follows: — xii. 1. a, 0, u, e, i — 5. 2. f, }),

r, k -4. 3. h, n, p, z, s — 3. 4. t, b, m, 1 — 4. And tbis is, in fact,

precisely the order of tbe consonants in tbe tbree groups of tbe pra3-Roman

alphabet of tbe Teutons as proved by tbe Futbark; and we migbt stop bere. For

tbe dispersion of tbe vowels among tbe consonants in tbe latter creates no

difficulty wbicb we are bound to account for. It probably only marks another

step in advance, when the Teutons gave up writing their Ogam on two

conterminous planes, and took to tbe laths or planed rods of historical

times, wbicb make it hopeless now to find an early specimen, and with regard

to wbicb Dr. Wimmer quotes the words of Venantius Fortunatus in tbe 6th

century: — " Barbara fraxineis pingatur runa tabellis, Quodque papyrus

agit, virgula plana valet." It may be supposed that it was found

inconvenient to distinguish four kinds of digits on one surface, and that

this led to one of them being given up. On what principle the vowels were

distributed in the other groups it is not easy to see; but the |

|

|

|

|

|

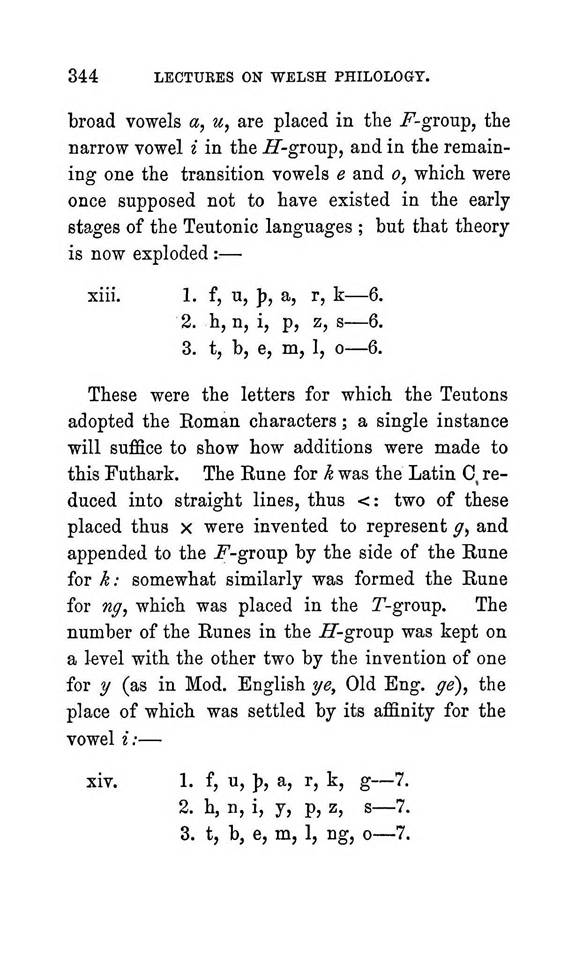

344 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. broad vowels a, u, are placed in

the i^-group, the narrow vowel i in the ZT-group, and in the remaining one

the transition vowels e and o, which were once supposed not to have existed

in the early stages of the Teutonic languages; but that theory is now

exploded:. — xiii. 1. f, u, ]j, a, r, k — 6. 2. h, n, i, p, z, s — 6, 3. t,

b, e, m, 1, o — 6. These were the letters for which the Teutons adopted the

Eoman characters; a single instance will suffice to show how additions were

made to this Futhark. The Eune for k was the Latin C, reduced into straight

lines, thus <: two of these placed thus x were invented to represent y,

and appended to the J'-group by the side of the Eune for k: somewhat

similarly was formed the Eune for ng, which was placed in the T-group. The

number of the Eunes in the ^ET-group was kept on a level with the other two

by the invention of one for y (as in Mod, English ye. Old Eng. ge), the place

of which was settled by its affinity for the vowel i: — xiv. 1. f, u, ]), a,

r, k, g — 7. 2. h, n, i, y, p, z, s— 7. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, ng, o — 7. |

|

|

|

|

|

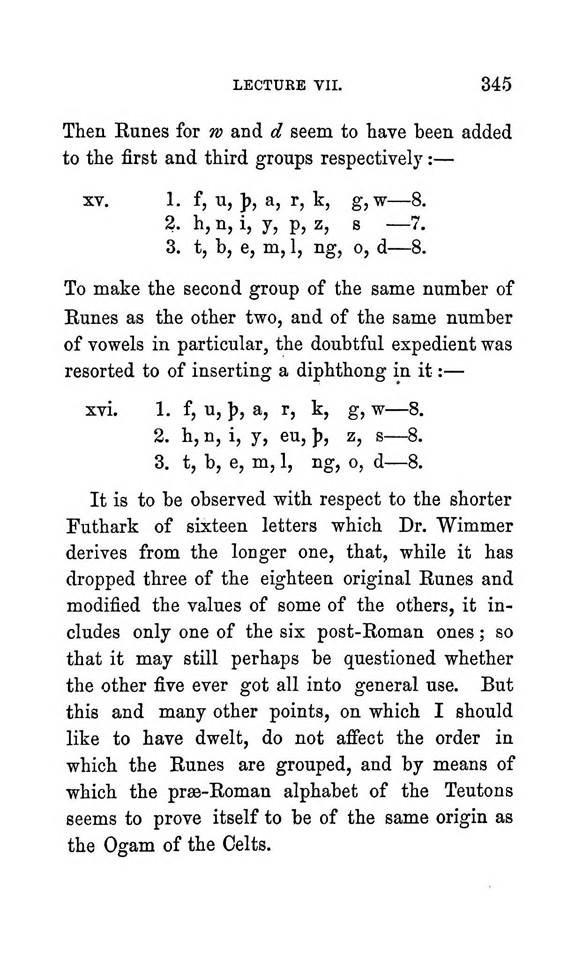

LECTUEE VII. 345 Then Eunes for w and d seem to have heen added to

the first and third groups respectively: — XV. 1. f, u, y, a, T, k, g,w — 8.

2. h, n, i, J, p, z, s —7. 3, t, b, e, m, 1, ng, o, d — 8. To make the second

group of the same number of Eunes as the other two, and of the same number of

vowels in particular, the doubtful expedient was resorted to of inserting a

diphthong in it: — xvi. 1. f, u, \), a, r, k, g, w — 8. 2. h, n, i, y, eu,

]>, z, s — 8. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, ng, o, d — 8. It is to be observed with

respect to the shorter Futhark of sixteen letters which Dr. Wimmer derives

from the longer one, that, while it has dropped three of the eighteen

original Eunes and modified the values of some of the others, it includes

only one of the six post-Eoman ones; so that it may still perhaps be

questioned whether the other five ever got all into general use. But this and

many other points, on which I should like to have dwelt, do not affect the

order in which the Eunes are grouped, and by means of which the prse-Eoman

alphabet of the Teutons seems to prove itself to be of the same origin as the

Ogam of the Celts. |

|

|

|

|

|

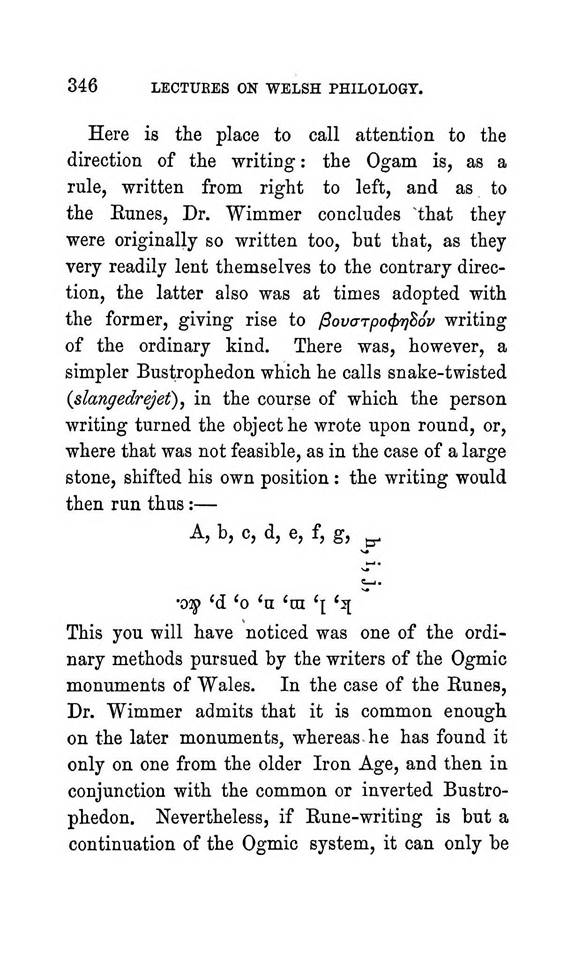

346 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. Here is the place to call

atteation to the direction of the writiDg: the Ogam is, as a rule, written

from right to left, and as to the Eunes, Dr. Wimmer concludes "that they

were originally so written too, but that, as they very readily lent

themselves to the contrary direction, the latter also was at times adopted

with the former, giving rise to ^ovarpo^Bov writing of the ordinary kind.

There was, however, a simpler Bustrophedon which he calls snake-twisted

(slangedrejet), in the course of which the person writing turned the object

he wrote upon round, or, where that was not feasible, as in the case of a

large stone, shifted his own position: the writing would then run thus: — A,

b, c, d, e, f, g, ^ C— I. •oig 'd 'o 'u 'm \ ^\ This you will have noticed

was one of the ordinary methods pursued by the writers of the Ogmic monuments

of Wales. In the case of the Eunes, Dr. Wimmer admits that it is common

enough on the later monuments, whereas- he has found it only on one from the

older Iron Age, and then in conjunction with the common or inverted

Bustrophedon. Nevertheless, if Eune-writing is but a continuation of the

Ogmic system, it can only be |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTURE VII. 347 an accident that it has not been more frequently

met with on the older monuments. The inverted Bustrophedon is to be met with

in some of the oldest Greek inscriptions, and occasionally in Etruscan ones,

whereas the simpler one is rarely detected in Greece or Italy, and its

appearance in Wales. and Teutonic countries is a point in favour of the view

that the Runes and the Ogam are connected with one another. Why both were

written mostly from left to right, while the Phoenicians wrote from right to

left is a question which I am not prepared to meet; but the answer is perhaps

to be sought in the fact, if such I am right in thinking it to be, that when

cutting a series of scores or notches on a piece of wood, one is able to work

with more ease and neatness by beginning at the end nearest one's self than

at the other. Assuming that it has been shown to be probable that the Ogam

and the prae-Runic alphabet of the Teutons are connected, one may ask how

they may be connected? that is, are we to regard one as derived from the

other, or both as independently derived from the Phoenician alphabet, whether

directly or indirectly? Clearly one has no business to try the latter

alternative, unless the other turn out inadmissible: then our first business

is to try to ascertain whether the Teutonic alphabet is derived from the

Celtic one or vice versa. Not |

|

|

|

|

|

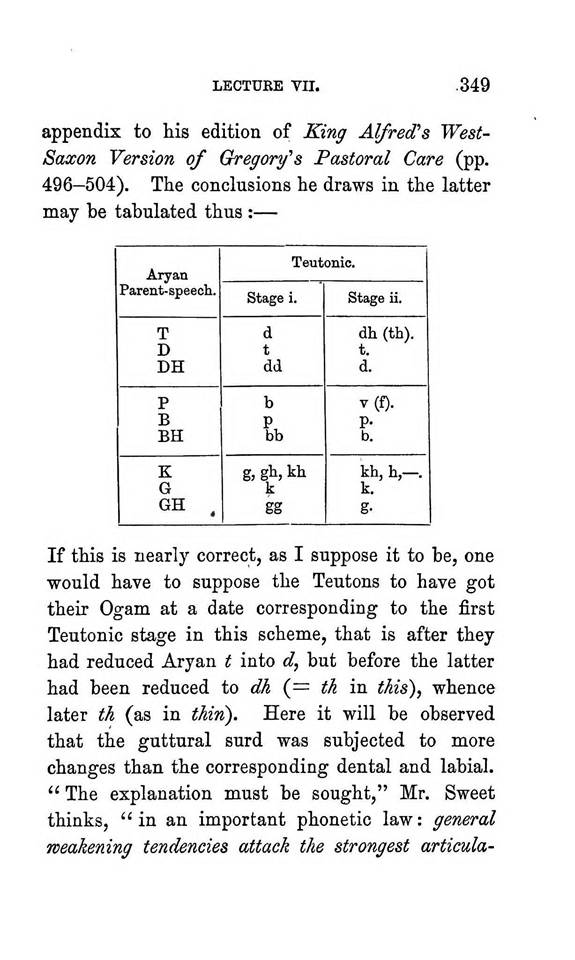

348 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY, to depart from the order we have

hitherto followed, we shall in the first place suppose the Celtic entitled to

precedence. In the absence of historical data the question must be settled on

phonological ground. We have a ready test in the Ogmic ch: how is it that,

while betk and daleth yielded Ogmic h and d, gimel on the other hand yielded

ch, and not g? To this the Celtic languages can give no answer, but the

Teutonic ones can, which compels us to suppose the Celts to have had their Ogam

alphabet from the Teutons, and derives confirmation from the fact that the

sound of ^ or _/ remained withoujt being provided for, at least by a strictly

Ogmic symbol. This leads me to consider very briefly some points in the

phonology of the Teutonic languages, which, I feel assured, you will consider

no hardship, seeing that the English we are at this moment using is one of

them, and that it is nearly related to our own Celtic vernacular. When it is

said with regard, for instance, to the words irrepdv and feather that the y

of the latter is the p of the former subjected to provection, this assigns

only the limits of the change: at any rate one of the latest writers . on the

subject would place between p and Teutonic / the intermediate steps of b and

v: I allude to Mr. Henry Sweet in his History of English Sounds (pp. 76-81),

and in an |

|

|

|

|

|

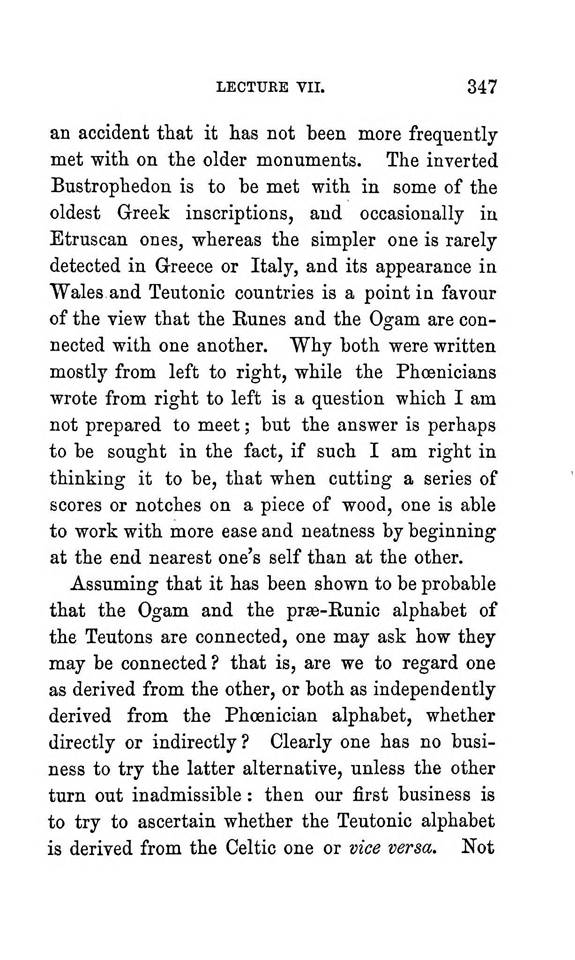

LECTDKE Vn. .349 appendix to his edition of King Alfred's

West-Saxon Version of Gregory's Pastoral Care (pp. 496—504). The conclusions

he draws in the latter may be tabulated thus: — Aryan Parent-speech. Teutonic. Stage i.

Stage ii. T D DH d t dd dh (th). d. P B BH b v(f). P- b. K G GH . gg kh, h -.

k. g- If this is nearly correct, as I

suppose it to be, one would have to suppose the Teutons to have got their

Ogam at a date corresponding to the first Teutonic stage in this scheme, that

is after they had reduced Aryan t into d, but before the latter had been

reduced to dh (= th in this), whence later th (as in thin). Here it will be

observed that the guttural surd was subjected to more changes than the

corresponding dental and labial. *' The explanation must be sought," Mr.

Sweet thinks, "in an important phonetic law: general weakening

tendencies attack the strongest articula-

|

|

|

|

|

|

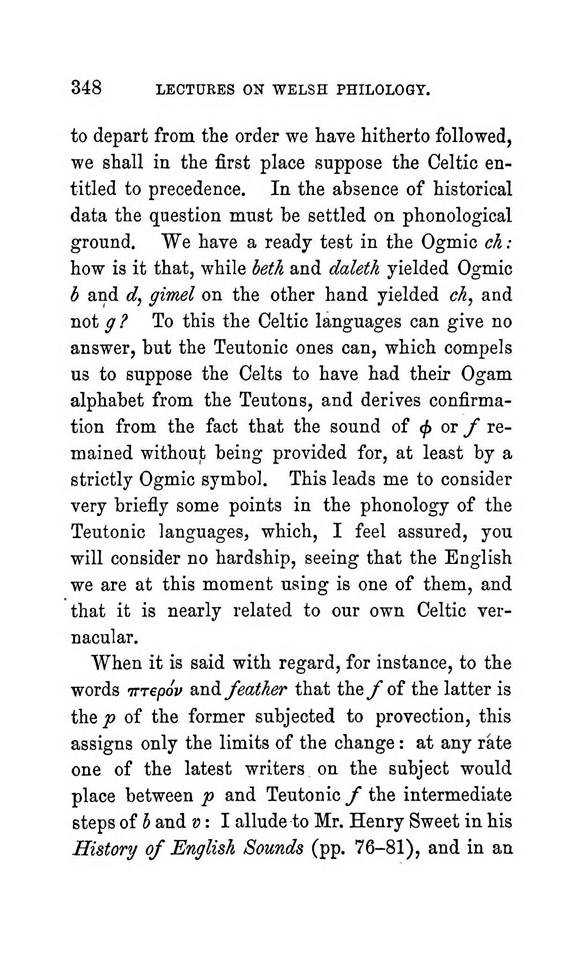

350 LECTUEES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. tions first. Accordingly we find

that while original d and b [our Teutonic stage i.] have only passed through

one stage of weakening, original initial g has passed through no less than

three: gh, kh, and h, in the last reaching the extreme of phonetic

decrepitude " (Appendix, p. 502). That is, the changes in question would

stand somewhat as follows if we regard only their chronological order: —

Phoenician . . h(eth), g(imel), d(aleth). Teutonic 1 . . b, g, d. ,, 2 . . b,

gh, d. ,, 3 . . b, kh, d. „ 4 . . V, h, dh. From this it appears that

Teutonic phonology fully meets the difficulty which presented itself in our

former supposition, and that we have, therefore, to abide by the other,

namely, that the Celts got their Ogam from the Teutons, and the latter

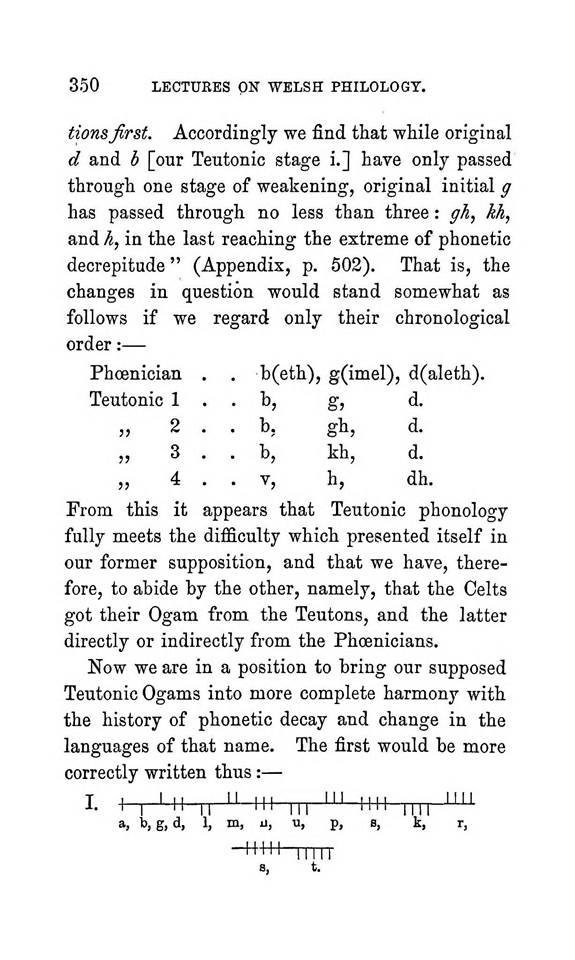

directly or indirectly from the Phoenicians. Now we are in a position to

bring our supposed Teutonic Ogams into more complete harmony with the history

of phonetic decay and change in the languages of that name. The first would

be more correctly written thus: — I. I I II I II I I I II III III n i l nil

"" a. b, g, d, 1, m, li, u, p, B, k, r, H-m-

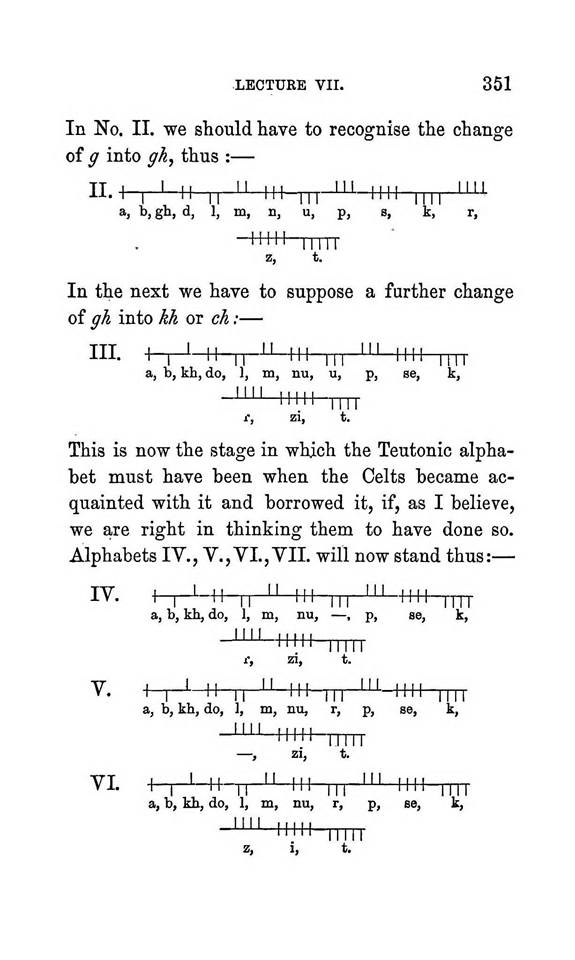

nrr t. -LECTURE VII. 351 In No.

II. we should have to recognise the change of g into gh^ thus: — II. I I I II

I I II I II i ii-iH I II I! a, b, gh, d, 1, m, n, u, p, 8, k, r. mil rmr z, t. In the next we have to suppose a

further change of gh into kk or ch: — III. 1 I I II II I' I I I I II III nil

ni l a, b, kh, do, ], m, nu, u, p, se, k, "" IM II mr /, Zl, t.

This is now the stage in which the Teutonic alphabet must have been when the

Celts became acquainted with it and borrowed it, if, as I believe, we are

right in thinking them to have done so. Alphabets IV., V., VI., VII. will now

stand thus: — IV. +^^- 11 II II III I I I '" MM i m- a, b, kh, do, 1, m,

nu, — , p, ae, k, III! inii ll'll-jiill r, zi, t. V. I I ' II II " I I I

I I I I'l nil n i l a, b, kh, do, 1, m, nu, r, p, se, k, "" mil ii

iii ZI, t. VI. -I-T-M+- II II III I I I III M i l nil a,

b, kh, do, 1, m, nu, r, p, se, k. |

|

|

|

|

|

1 1 " n i l i, t. |

|

|

|

|

|

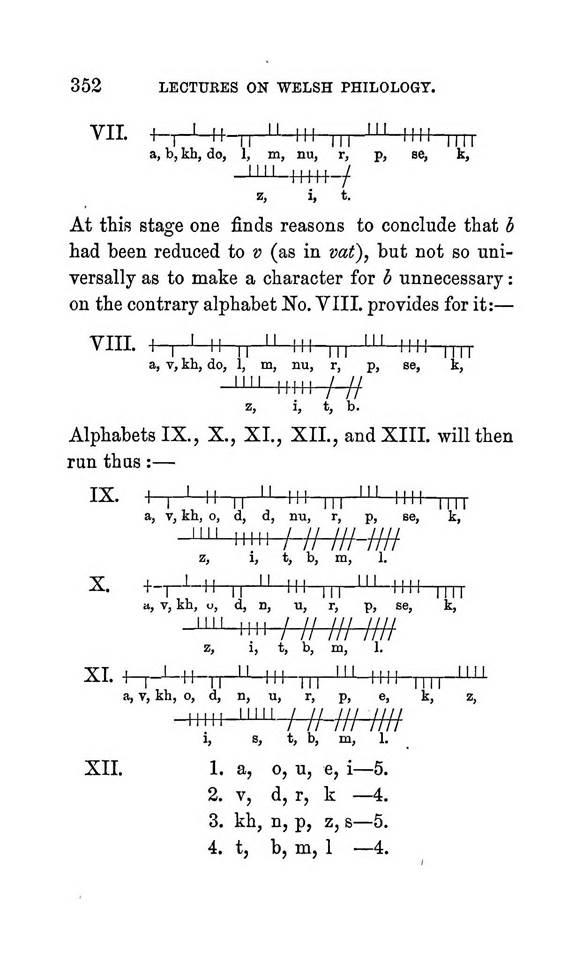

352 LEOTUKES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. ^"- n ,' ' " N "

'" IN '" "" II" a, 0, kn, do, 1, m, nu, r, p, se, k,

I ' ll m i l -/ z, i, t. At this stage one finds reasons to conclude that b

had been reduced to v (as in vat), but not so universally as to make a

character for b unnecessary: on the contrary alphabet No. VIII. provides for

it: — VIII. I I I I I I , I I II I I I I I I I nil n i l a, V, kh, do, 1, m,

nu, r, p, se, k, i i ' i mil / // z, i, t, b. Alphabets IX., X., XL, XII.,

and XIII. will then run thas: — IX. I I I I I II Ill III n i l n i l a, V,

kh, o, d, d, rni, r, p, se, k, "" iNii I II iii -m z, 1, t, b, m,

1. X. +-^^ 11 I I II III III ' " nil nil a, V, kh, u, d, n, u, r, p, se,

k, "" I'M I II III nil z, 1, t, b, m, 1. XL ^T^+i- n II 11 1 III

'" II " mi "" a, V, kh, 0, d, n, u, r, p, e, k, z, I '

'" I II III nil i, B, t, b, m, 1. XII. 1. a, 0, u, e, i — 5. 2. V, d, r,

k —4. 3. kh, n, p, z, 6 — 5. 4. t, b, m, 1 — 4. |

|

|

|

|

|

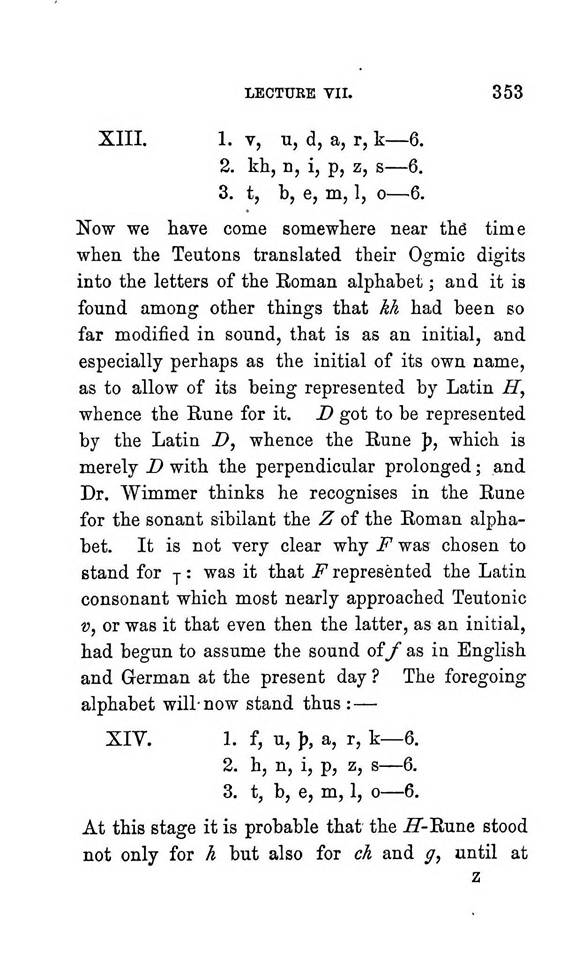

LECTURE VII. 353 XIII. 1. V, u, d, a, r, k — 6. 2. kh, n, i, p, z,

s — 6. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, o — 6. Now we have come somewhere near ths time when

the Teutons translated their Ogmic digits into the letters of the Eoman

alphabet; and it is found among other things that kk had been so far modified

in sound, that is as an initial, and especially perhaps as the initial of its

own name, as to allow of its being represented by Latin H, whence the Rune

for it. D got to be represented by the Latin Z>, whence the Rune p, which

is merely D with the perpendicular prolonged; and Dr. Wimmer thinks he

recognises in the Rune for the sonant sibilant the Z of the Roman alphabet.

It is not very clear why F was chosen to stand for j: was it that F

represented the Latin consonant which most nearly approached Teutonic V, or

was it that even then the latter, as an initial, had begun to assume the

sound ofy as in English and German at the present day? The foregoing alphabet

will- now stand thus: — XIV. 1. f, u, J), a, r, k— 6. 2. h, n, i, p, z, s —

6. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, o — 6. At this stage it is probable that the S'-Rune

stood not only for k but also for cA and y, until at |

|

|

|

|

|

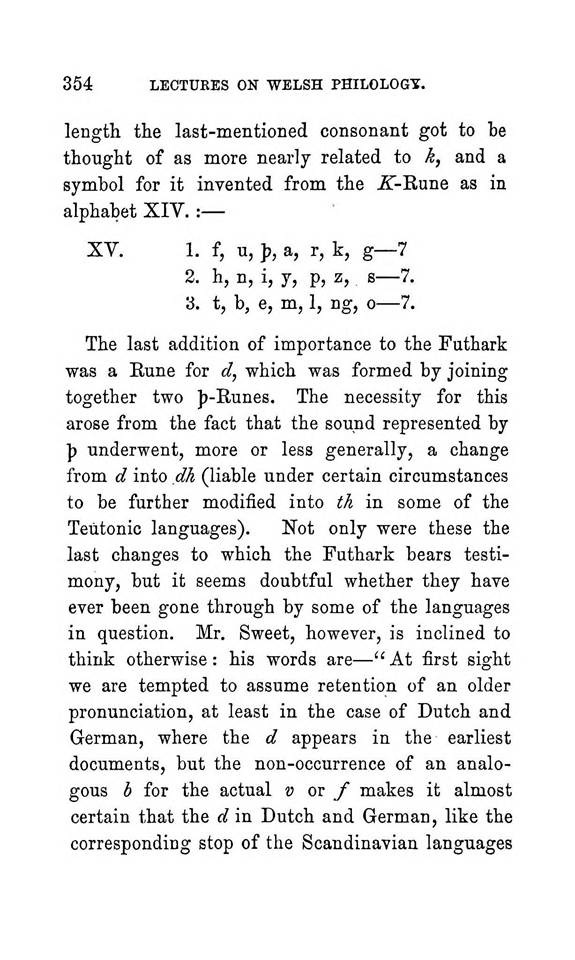

354 LECTUKES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. length the last-mentioned

consonant got to he thought of as more nearly related to k, and a symbol for

it invented from the ^-Rune as in alphabet XIV.:— XY. 1. f, u, J), a, r, k,

g— 7 2. h, n, i, y, p, z, . s— 7. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, ng, o — 7. The last

addition of importance to the Futhark was a Eune for d, which was formed by

joining together two J)-E.unes. The necessity for this arose from the fact

that the sound represented by ]) underwent, more or less generally, a change

from d into _dh (liable under certain circumstances to be further modified

into th in some of the Teutonic languages). Not only were these the last

changes to which the Futhark bears testimony, but it seems doubtful whether

they have ever been gone through by some of the languages in question. Mr.

Sweet, however, is inclined to think otherwise: his words are — "At

first sight we are tempted to assume retention of an older pronunciation, at

least in the case of Dutch and German, where the d appears in the earliest

documents, but the non-occurrence of an analogous h for the actual w or _/

makes it almost certain that the d in Dutch and German, like the

corresponding stop of the Scandinavian languages |

|

|

|

|

|

LECTUEE VII. 355 has arisen from earlier dh " (App. p. 499).

The Fathark, then, in its complete state is the following, which has already

been more than once mentioned: — XVI. 1. f, n, ],, a, r, k, g, w— 8. 2. h, n,

i, y, en, p, z, s — 8. 3. t, b, e, m, 1, ng, o, d — 8. It is right, however,

to state that some Futharks lack some of the additional Eunes alluded to,

while others have several more than have here been mentioned; moreover, while

the latter are placed at the end, there is, as might be expected, some

-difference as to where the former are inserted in the Futharks containing

them. Thus on a knife found in the Thames in 1857, and guessed to date about

the year 700, the order is as follows: — 1. f, u, J), a, r, k, g, w— 8. 2. h,

n, i, y, eu, p, z, s — 8. 3. t, b, e, ng, d, 1, m, o — 8. It will here be

observed that the Eunes for ng and d have been inserted next each other after

e, but without inverting their order, in the third group, which is otherwise

highly interesting as giving us the variant sequence I, m. Before proceeding

further a word may not be here out of place as to the number of changes

crowded into our conjectured history of the Ogam, |

|

|

|

|

|

356 LECTURES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. whether Celtic or Teutonic. In

the first place, then, that crowding is more apparent than real, as the Ogam

seems to have been many centuries in use before the oldest specimens known to

us were produced. On the other hand it is not to be overlooked, that an

alphabet like the Ogam, which is composed of scores and groups of scores

would naturally change much faster than if it were not so, as a change in

respect of one symbol would naturally induce other changes, which need not

take place in an alphabet consisting of symbols the individuality of which

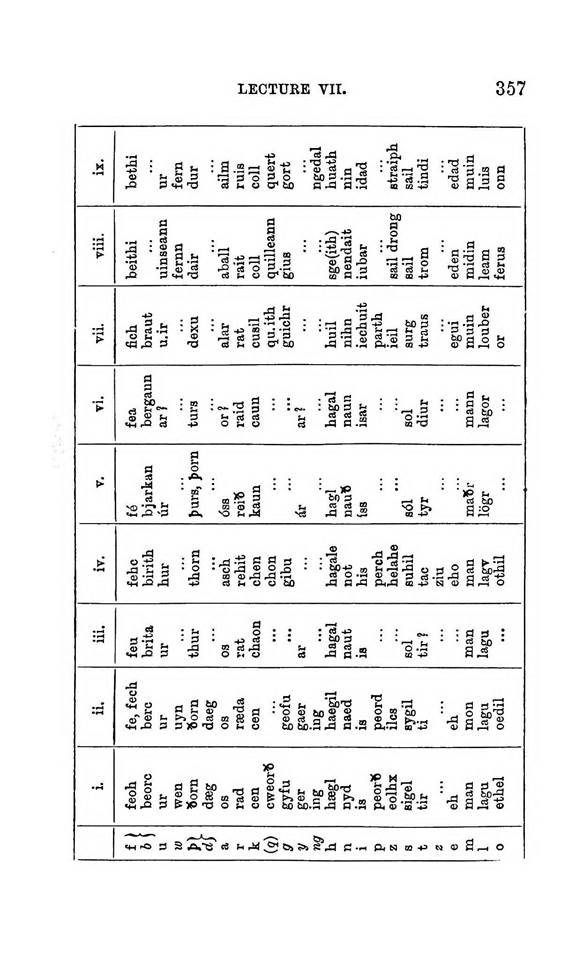

depends on their difference of form. Now I shall have to say something on the

difficult question of the names of these letters; but I can only call your

attention to a few of the leading facts, passing by many points which I

cannot profess to deal with. Any one, however, who wishes to make a special

study of this subject will have to consult Mr. George Stephens's massive work

on The Old Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England (London and

Copenhagen, 1866-67). Perhaps I could not here do better than place side by

side a certain number of the alphabets in point for your inspection. The

names in column i. are from an alphabet contained in an old English

manuscript ( Cotton. Otho. B. 10) now lost: it has been hesitatingly assigned

to the 9th century by Mr. |

|

|

|

|

|

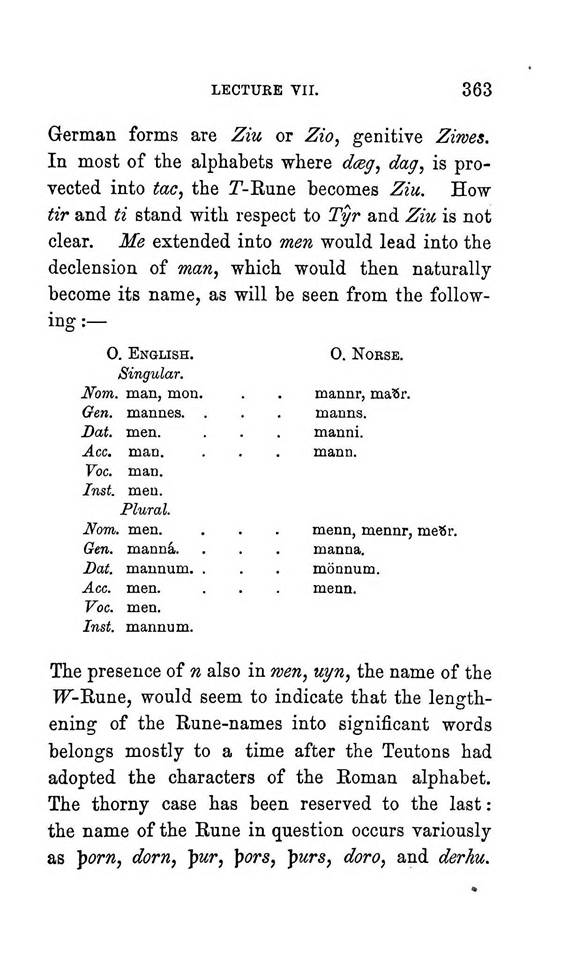

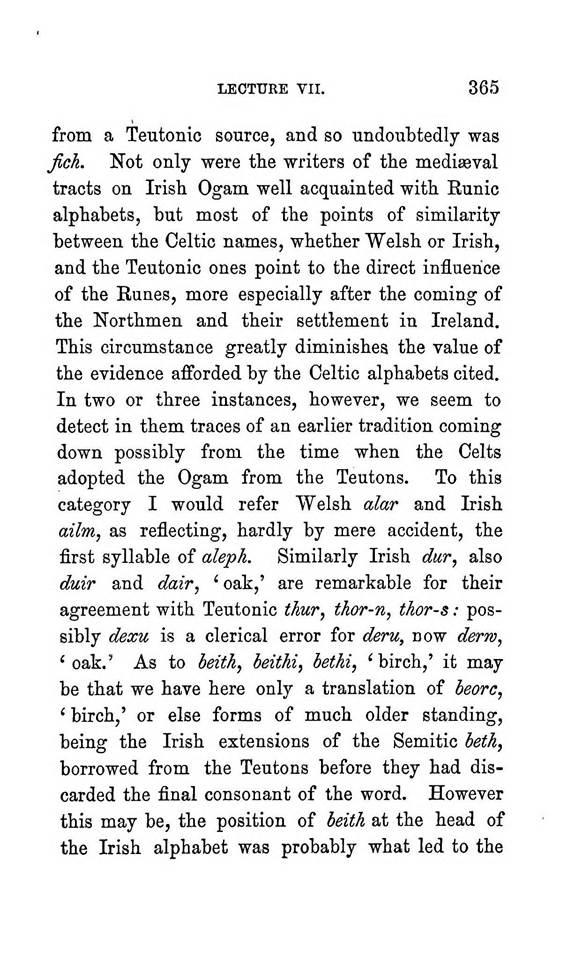

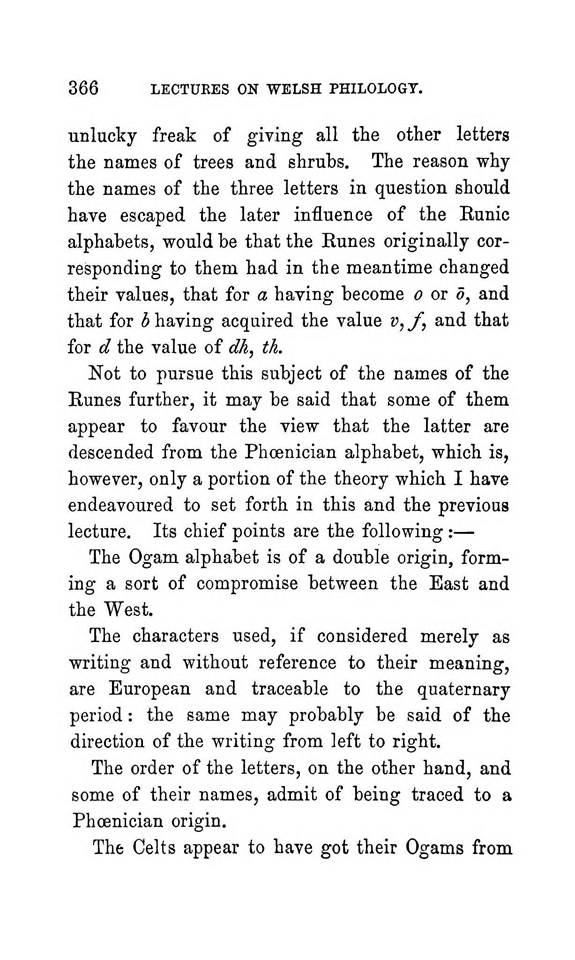

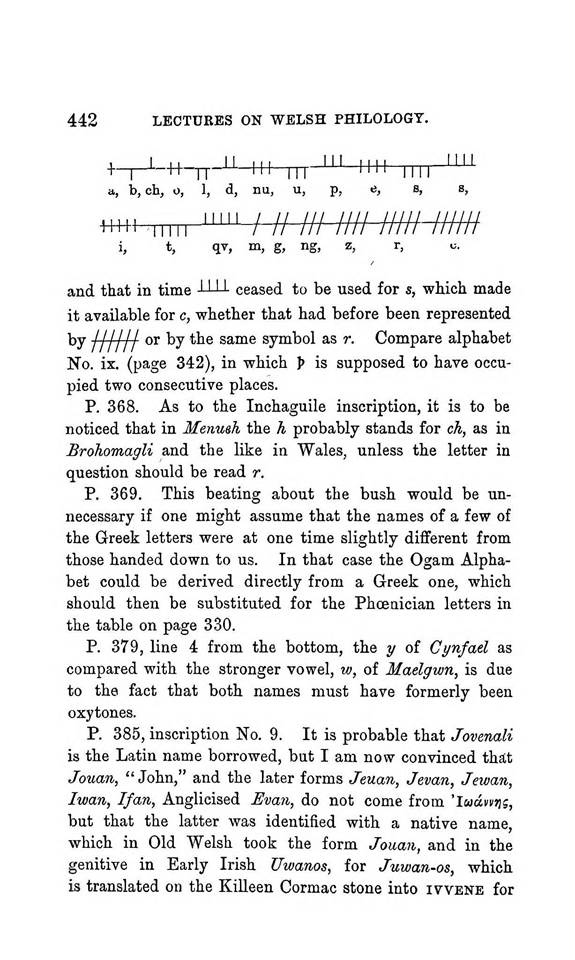

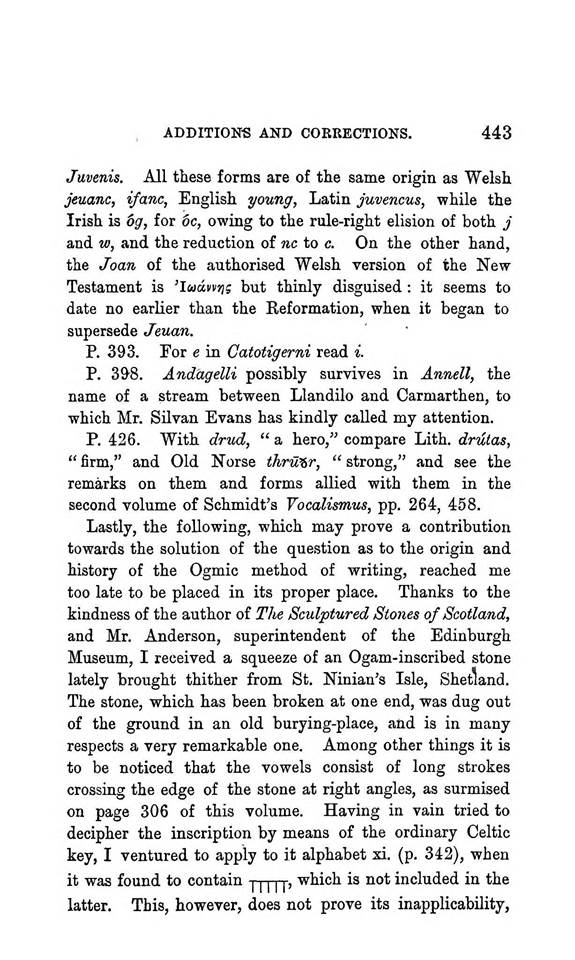

LECTURE vn. 357 f^ 9

9 ,£> •5 » ,S -2 3 9 s -3 So S a S s ° -o 3 g

S 1 1 =• 'I '1"^ " s,'E, ■

'1=3 1 g.^ = - ■ &i g ^ H

o i^ a^ 3 .JO, .:;: •::: , S^-3 rfi,>o2j« se JH.2 aS" BS s '. f-* '. Oil;«343:: e— ";dc3 _, fl cio JS: *2 t4 "Sots t, itj: d h

^ 1 i . I i r.-s g life g-'i'U Jll.

=^ I |l >M MS 3 2 ,a.-i3 <8

h,J^35»!*S^ c.« p,N n*3 « 0) Srf o |

|

|

|

|

|

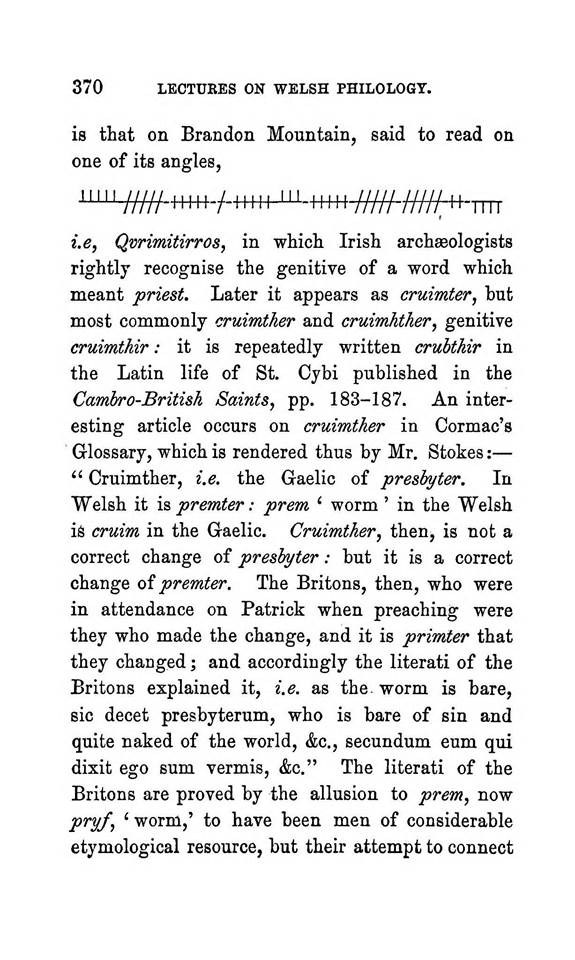

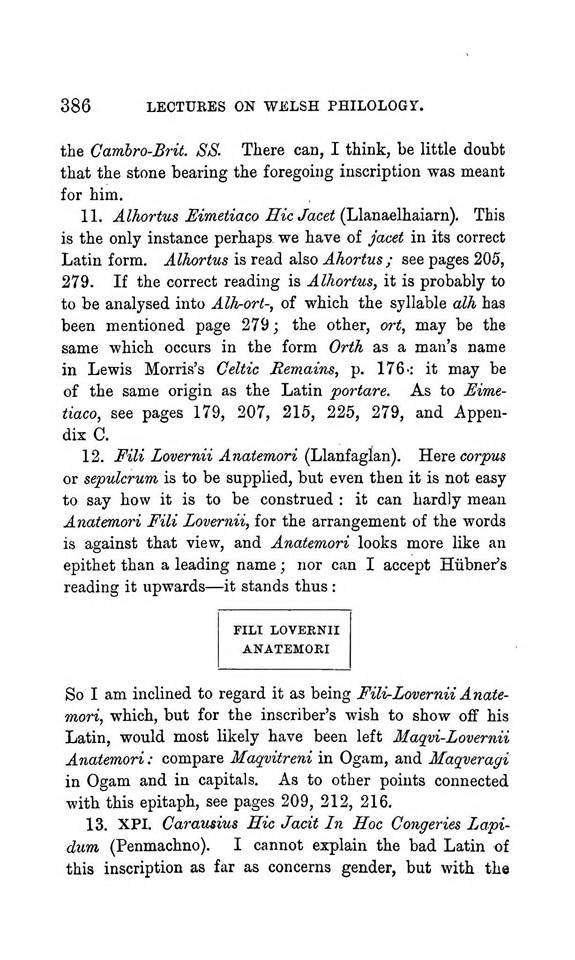

358 LBCTUEES ON WELSH PHILOLOGY. Stephens, whose No. 5 it forms: a

copy of it is also given in fac-simile by Dr. Wimmer, p. 79. Column ii. is

taken from an alphabet in a Vienna MS. {Codex Salisb. 140) which Grimm

supposed to be a transcript from an English original brought to Germany

towards the end of the 8th century: the transcript is considered as dating

from the end of the 9th century or the beginning of the 10th by Dr. Wimmer,

who gives a fac-simile of it by the side of the one just mentioned. Column

iii. is from the so-called Abecedarium Nordmannicum of a St. Gall manuscript

of the 9th century: it forms Stephens's No. 6, and is given in fac-simile by

Wimmer, p. 191. Column iv. is copied from Stephens's No. 46, and comes from a

Yienna manuscript ( Cod. 64): it appears to be of High German origin. Column

v. is from Wimmer's names of the letters of the shorter Futhark as he finds

it used in the later Iron Age in the North, p. 153. Column vi. is the same,

as given in the Book of Ballymote, an Irish MS. of the 14th century, extracts