.....

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7795a) (tudalen clawr)

|

A GLOSSARY

OF

PROVINCIAL WORDS

USED IN

HEREFORDSHIRE.

1839.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7795b) (tudalen iii)

|

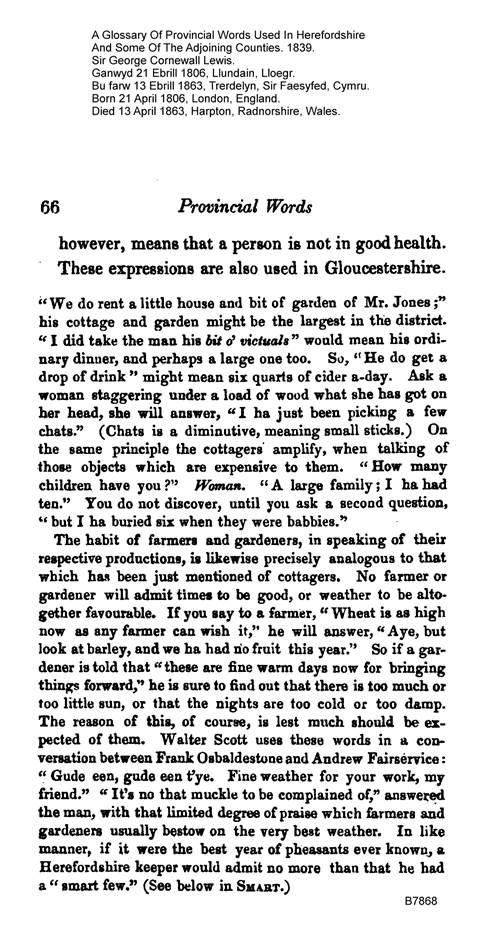

A Glossary Of

Provincial Words Used In Herefordshire And Some Of The Adjoining Counties.

1839.

Sir George Cornewall Lewis.

Ganwyd 21 Ebrill 1806, Llundain, Lloegr.

Bu Farw 13 Ebrill 1863, Trerdelyn, Sir Faesyfed, Cymru. (56 Oed).

A Glossary Of

Provincial Words Used In Herefordshire And Some Of The Adjoining Counties.

London. John Murray,

Albemarle-Street. 1839.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7795c) (tudalen iv)

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7795d) (tudalen v)

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7796) (tudalen vi)

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7797) (tudalen vii)

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7798) (tudalen viii)

|

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7799) (tudalen ix)

|

|

|

|

|

|

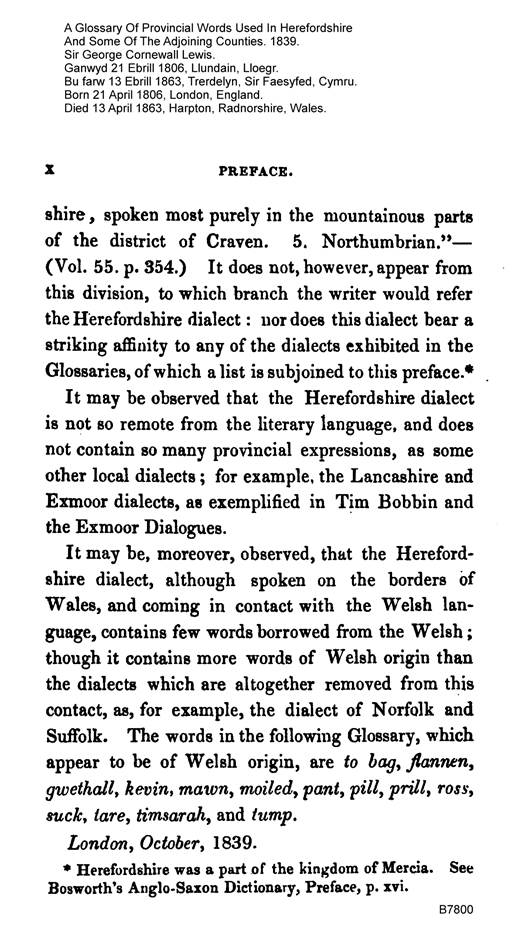

(delwedd B7800) (tudalen x)

|

|

|

|

|

|

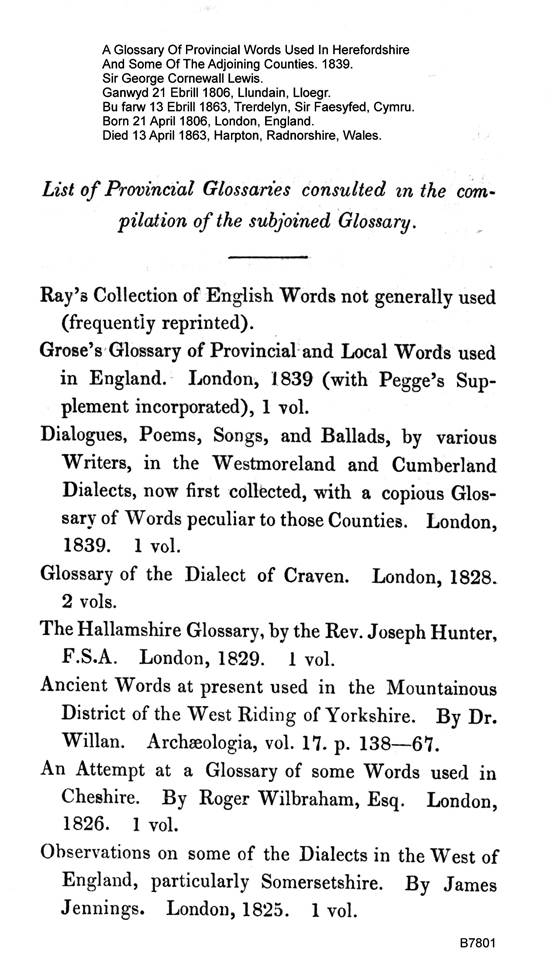

(delwedd B7801) (tudalen xi)

|

|

|

|

|

|

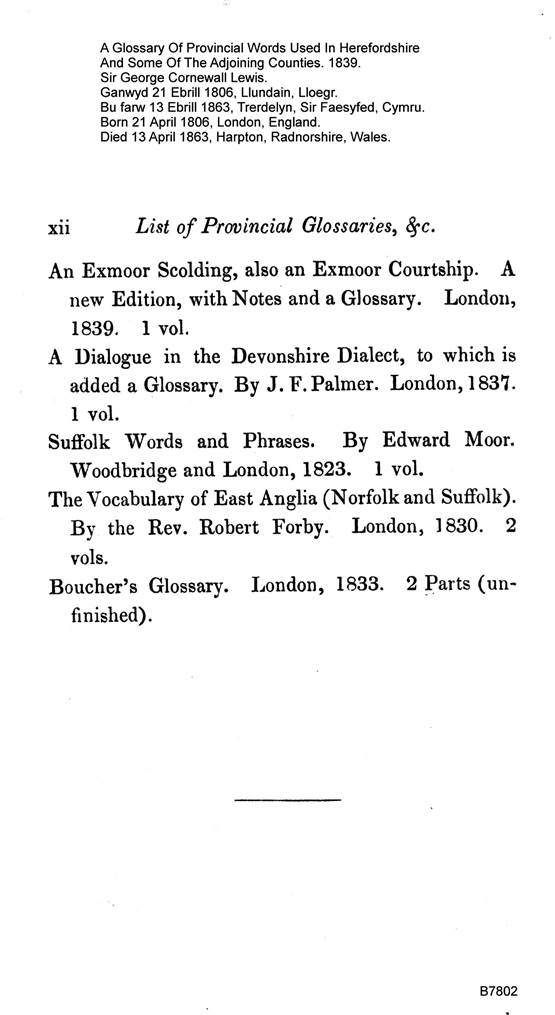

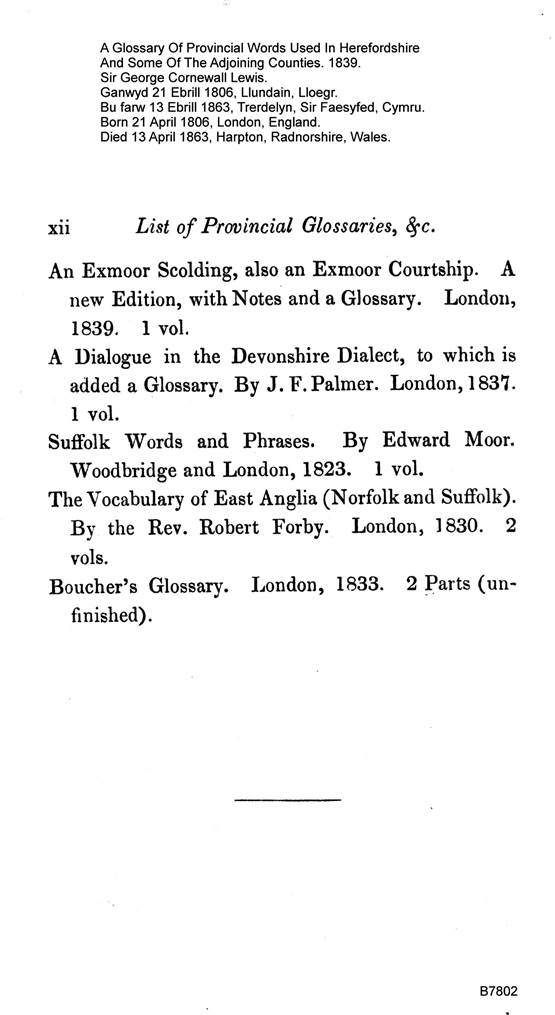

(delwedd B7802) (tudalen xii)

|

|

|

|

|

|

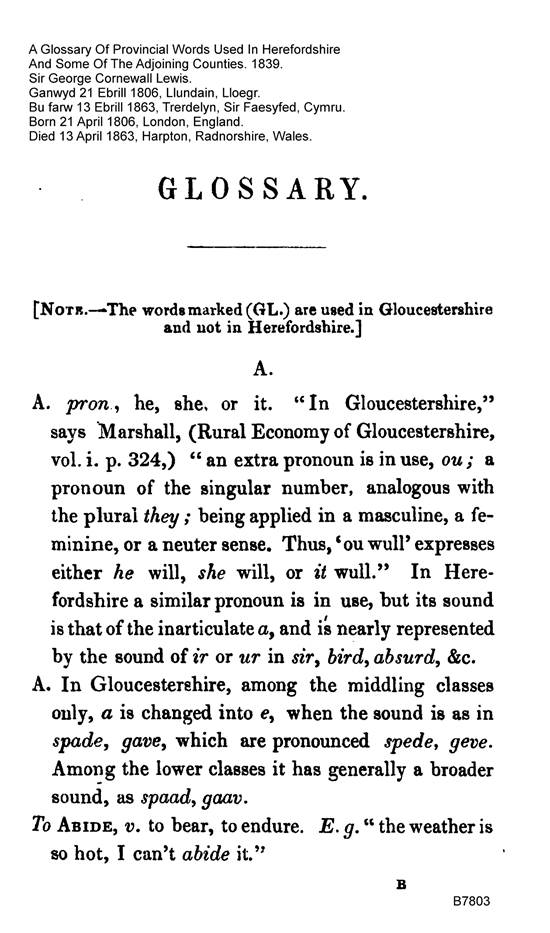

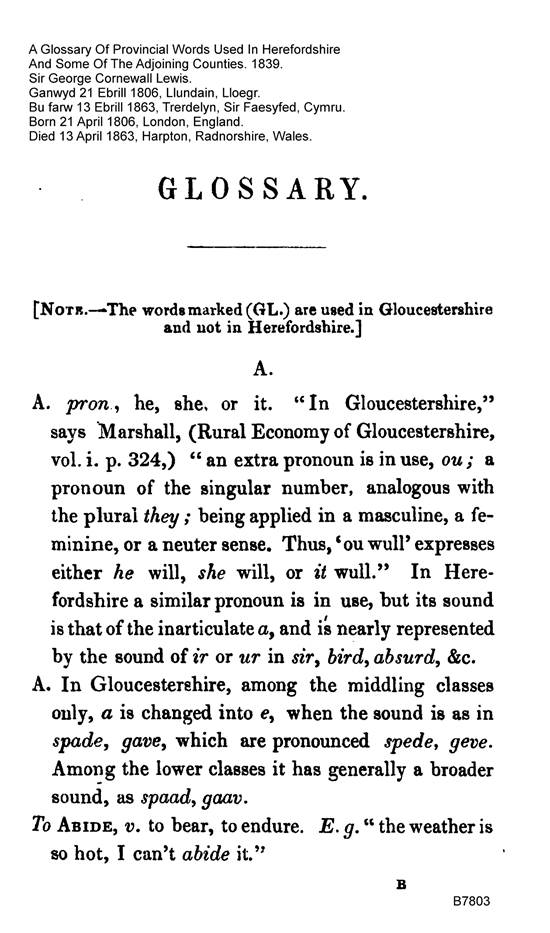

(delwedd B7803) (tudalen 001)

|

GLOSSARY.

[Note. — The words marked (GL.) are used in

Gloucestershire and not in Herefordshire.]

A.

A. pron , he, she, or it. “In Gloucestershire," says Marshall, (Rural

Economy of Gloucestershire, vol. i. p. 324,) “an extra pronoun is in use, ou;

a pronoun of the singular number, analogous with the plural they; being

applied in a masculine, a feminine, or a neuter sense. Thus, c ou wulP

expresses either he will, she will, or it wull." In Herefordshire a

similar pronoun is in use, but its sound is that of the inarticulate a, and

is nearly represented by the sound of ir or ur in sir 9 bird, absurd, &c.

A. In Gloucestershire, among the middling classes only, a is changed into e,

when the sound is as in spade, gave, which are pronounced spede, geve. Among

the lower classes it has generally a broader sound, as spaad, gaav.

To Abide, v. to bear, to endure. E. g. “the weather is so hot, I can't abide

it."

B

|

|

|

|

|

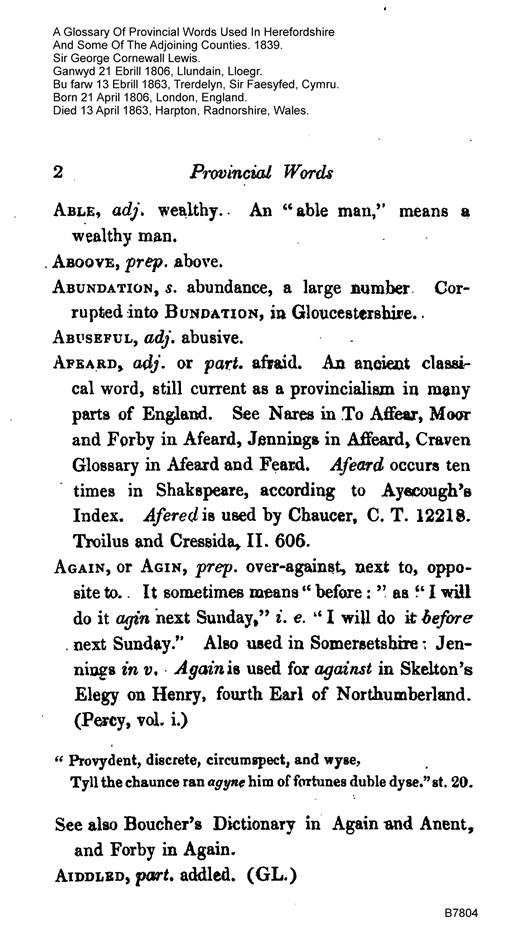

(delwedd B7804) (tudalen 002)

|

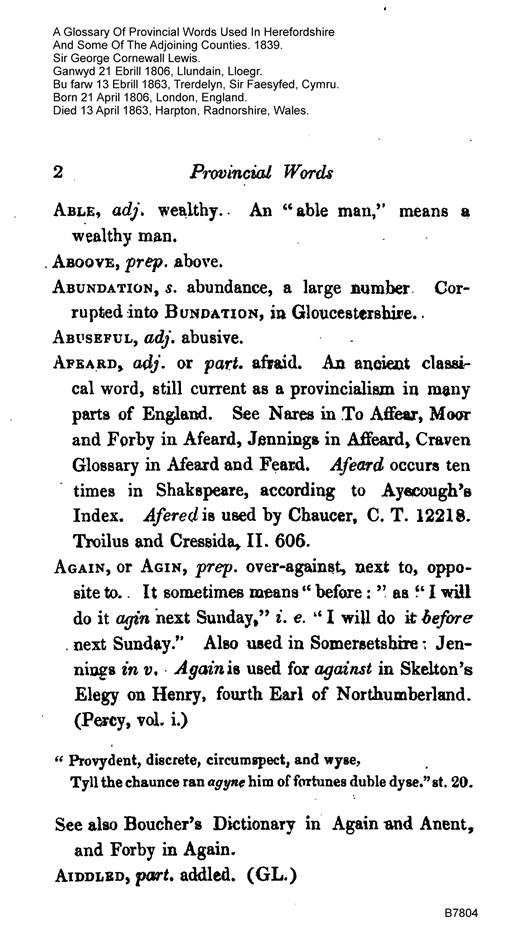

2 Provincial Words

Able, adj. wealthy. An "able man,' 5 means a wealthy man.

Aboove, prep, above.

Abundation, s. abundance, a large number Corrupted into Bundation, in

Gloucestershire.

Abuseful, adj. abusive.

Afeard, adj. or fart, afraid. An ancient classical word, still current as a

provincialism in many parts of England. See Nares in To AfTear, Moor and

Forby in Afeard, Jennings in AfFeard, Craven Glossary in Afeard and Feard.

Afeard occurs ten times in Shakspeare, according to Ayscough's Index.

Aferedia used by Chaucer, C. T. 12218. Troilus and Cressida, II. 606.

Again, or Agin, prep, over-against, next to, opposite to. It sometimes means

“before:” as “I will do it agin next Sunday," i. e. u I will do it

before next Sunday/' Also used in Somersetshire; Jennings in v. Againis used

for against in Skelton's Elegy on Henry, fourth Earl of Northumberland. (Percy,

vol. i.)

r * Provydent, discrete, circumspect, and wyse,

Tyll the chaunce ran agyne him of fortunes duble dy se." st. 20.

See also Boucher's Dictionary in Again and Anent,

and Forby in Again. Aiddled, part, addled. (GL.)

|

|

|

|

|

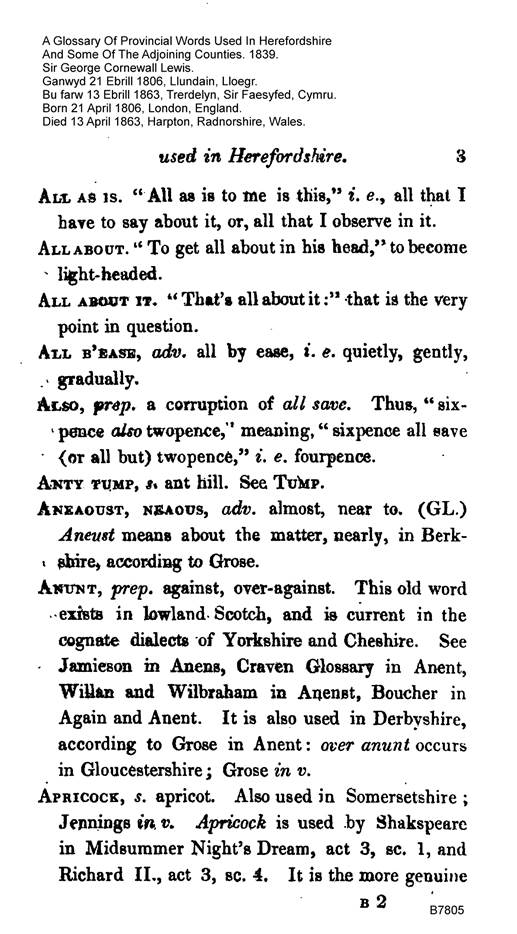

(delwedd B7805) (tudalen 003)

|

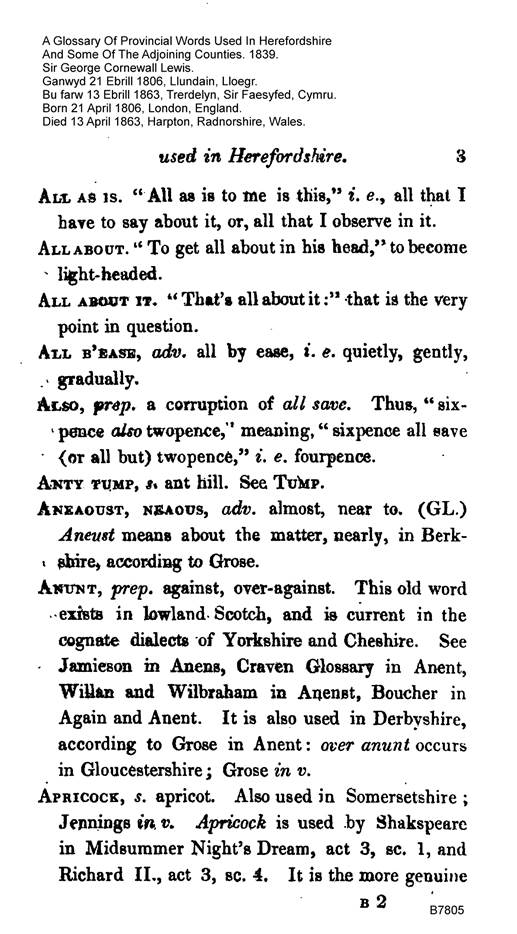

used in Herefordshire. 3

All as is. “All as is to me is this," i. e., all that I have to say

about it, or, all that I observe in it.

All about. “To get all about in his head," to become light-headed.

All about it. “That's all about it:" that is the very point in question.

All b'ease, adv. all by ease, i. e. quietly, gently, gradually.

Also, prep, a corruption of all save. Thus, “sixpence also twopence,"

meaning, “sixpence all save (or all but) twopence," i. e. fourpence.

Anty tump, s. ant hill. See Tump.

Aneaoust, neaous, adv. almost, near to. (GL.) Anevst means about the matter,

nearly, in Berkshire, according to Grose.

Anunt, prep, against, over-against. This old word exists in lowland Scotch,

and is current in the cognate dialects of Yorkshire and Cheshire. See Jamieson

in Anens, Craven Glossary in Anent, Willan and Wilbraham in Anenst, Boucher

in Again and Anent. It is also used in Derbyshire, according to Grose in

Anent: over anunt occurs in Gloucestershire; Grose in v.

Apricock, s. apricot. Also used in Somersetshire; Jennings in v. Apricock is

used by Shakspeare in Midsummer Night's Dream, act 3, sc. 1, and Richard II.,

act 3, sc. 4. It is the more genuine.

b 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7806) (tudalen 004)

|

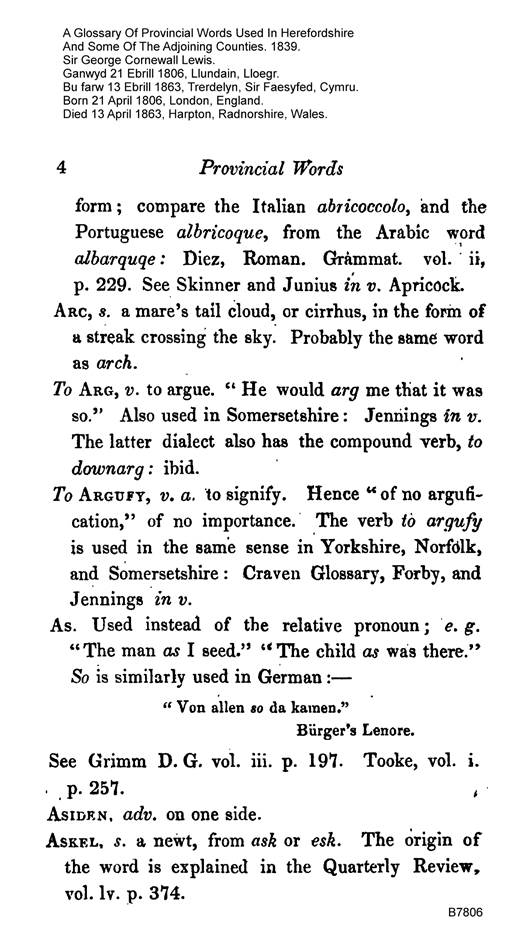

4 Provincial Words

form; compare the Italian abricoccolo, and the Portuguese albricoque^ from

the Arabic word albarquqe: Diez, Roman. Grammat. vol. ii, p. 229. See Skinner

and Junius in v. Apricock.

Arc, s. a mare's tail cloud, or cirrhus, in the form of a streak crossing the

sky. Probably the same word as arch.

To Arg, v. to argue. “He would arg me that it was so." Also used in

Somersetshire: Jennings in v. The latter dialect also has the compound verb,

to downarg: ibid.

To Argufy, v.a. to signify. Hence “of no argufication," of no

importance. The verb to argufy is used in the same sense in Yorkshire,

Norfolk, and Somersetshire: Craven Glossary, Forby, and Jennings in v.

As. Used instead of the relative pronoun; e, g. "The man as I

seed." “The child as- was there." So is similarly used in German: —

" Von alien so da kamen."

Burger's Lenore.

See Grimm D. G. vol. iii. p. 197. Tooke, vol. i.

p. 257. Aside n, adv. on one side. Askel, s. a newt, from ask or esk. The

origin of

the word is explained in the Quarterly Review,

vol. lv. p. 374.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7807) (tudalen 005)

|

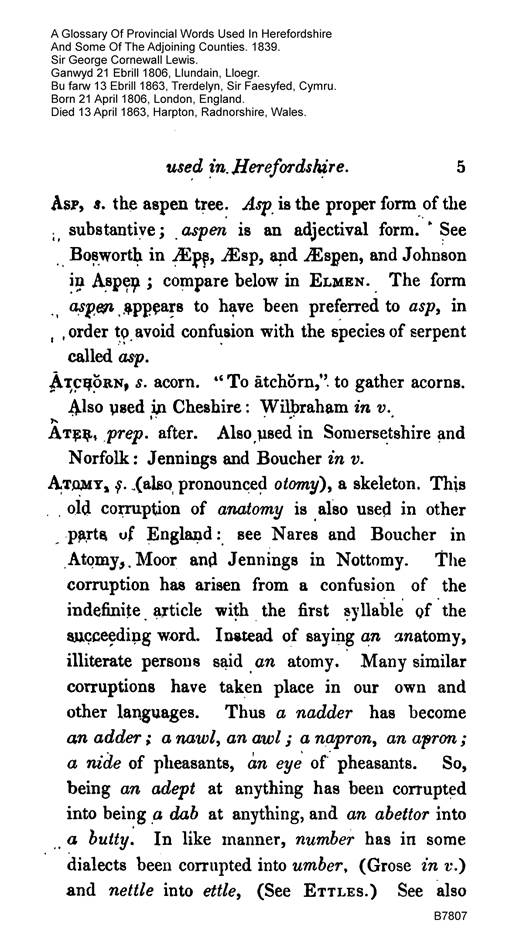

used in Herefordshire. 5

Asp, s. the aspen tree. Asp is the proper form of the substantive; aspen is

an adjectival form. See Bosworth in iEps, JEsp, and iEspen, and Johnson in

Aspen; compare below in Elmen. The form aspen appears to have been preferred

to asp, in order to avoid confusion with the species of serpent called asp.

Atchorn, s. acorn. “To atchorn," to gather acorns. Also used in Cheshire:

Wilbraham in v.

Ater, prep, after. Also used in Somersetshire and Norfolk: Jennings and

Boucher in v.

Atomy, s. (also pronounced otomy), a skeleton. This old corruption of anatomy

is also used in other parts of England: see Nares and Boucher in Atomy, Moor

and Jennings in Mottomy. The corruption has arisen from a confusion of the indefinite

article with the first syllable of the succeeding word. Instead of saying an

anatomy, illiterate persons said an atomy. Many similar corruptions have

taken place in our own and other languages. Thus a nadder has become an adder;

a nawl> an aivl; a napron, an apron; a nide of pheasants, an eye of

pheasants., So, being an adept at anything has been corrupted into being a

dab at anything, and an abettor into a butty. In like manner, number has in

some dialects been corrupted into umber \ (Grose in v.) and nettle into

ettle, (See Ettles.) See also

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7808) (tudalen 006)

|

6 Provincial Words

Tyrwhitt's Glossary to Chaucer in Nale, and Boucher's Dictionary in An. In

Italian, una apecchia has become una pecchia; una aguglia, una guglia; V

Alamagna, la Magna, and /' analomia, la notomia. On the other hand, /' onza, I'

or dura, have become la lonza, la lor dura. In French, m'amie has become ma

mie, and VApouille, la Pouille; whilst Voisir has become le loisir, and Vendemain

has become le lendemain, (like the tother in English.)

Audacious, adj. not shy, insolent.

Aul, or orl, s. an alder. Alor, air, A.S. Pronounced aller in Devonshire and

Somersetshire: Palmer and Jennings in v. The following are proverbial lines:

—

" When the bud of the aul is as big as the trout's eye, Then that fish

is in season in the river Wye."

In Yorkshire and Derbyshire, an alder is called an owler: Grose and Hunter in

v.

Aulen, adj. of alder, as “the aulen coppice," “an aulen pole."

Compare Elmen.

To Awhile, v. n. Used only in the expression, “I can't awhile," I can't

wait, I have no time, that is, probably, “I can't have while."

To Ax, v.a. to ask. This old form of the word (see Nares in v.) seems to be

current as a provincialism in most parts of England. It occurs in the Craven

Glossary, Hunter's Hallamshire Glossary,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7809) (tudalen 007)

|

used in Herefordshire. 1

Moor's Suffolk Words, Forby's East- Anglian Vocabulary, Jennings's

Somersetshire Glossary, and Palmer's Devonshire Glossary. It is also Scotch: see

Jamieson in v. Compare Boucher in v.

B.

Backside, s. the back; as, the backside of the wood, the house, &c. E.g.

"Did you see maister?" “No: he went out at the backside now

just."

Bad, adj. "Bad to do in the world," is opposed to “well to do in

the world." Poor, in straitened circumstances.

To Bag, v.a. to bag peas is to cut them with a hook, resembling the common

reaping-hook, but with a handle long enough to admit of both hands being applied

to it. This expression is used in a nearly similar sense in Gloucestershire,

and also according to Boucher, in Shropshire. Boucher says, “I suspect the

people of these counties borrowed this term (bagging hook) from their

neighbours the Welsh; adding to bach a hook, the English of it."

Bait, s, a meal taken by a labourer in the middle of the day.

Bald-rib, s. spare-rib. Also used in Gloucestershire. It is spelt ballrib in

Jennings's Somersetshire Glossary.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7810) (tudalen 008)

|

8 Provincial Words

Banky, adj. U a banky piece," a field with banks in it.

Bannut-tree, s. a walnut-tree bearing small fruit. This word is stated by

Jennings, p. 10, to be also used in the northern parts of Somersetshire. In Grose's

Glossary, the expression “bannet-tree” for walnut-tree is stated to be used

in Gloucestershire.

Barm, s. yeast, from beorma, A.S. A word used in other parts of the country.

See Boucher in v. It is pronounced burnt in Devonshire: Palmer in v.

Bash, s. 1. the mass of the roots of a tree before they separate. In Grose's

Glossary, tc bashy" is stated to be a north-country word for “fat,

swelled." In Norfolk, according to Forby, "to cut a bosh, is something

stronger than the more usual expression to ' cut a dash;' something more

showy and expensive." Forby states that bosen out is rendered by tumidus

in the Promtuarium Parvulorum; and he compares the French bosse. See also

Grose in Bosh. The word svjell is similarly used in modern slang language:

Compare the description of the approach of Dalila, in Samson Agonistes, v.

710. 2. Bash is also used to signify the front of a bull's or pig's head.

Pash is a ludicrous term for the head in Scotch: Jamieson in v. Bash in this

sense appears to be derived from to bash or pash, to strike^ or push: see

Todd's Johnson, Forby and

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7811) (tudalen 009)

|

used in Herefordshire. 9

Crav. Glossary, in Pash, and Jamieson in Bash. The word pash occurs in this

sense in Winter's Tale:—

Leontes. How now, you wanton calf?

Art thou my calf?

Mamillius. Yes, it' you will, my Lord. Leont. Thou want'st a rough pash, and

the shoots

that I have,

To be full like me, — Act I. sc. 2.

Which passage is correctly explained by M alone thus: ct You tell me that you

are like me; that you are my calf. I am the horned bull; thou wantest the

rough head and the horns of that animal, completely to resemble your

father." A mad-brained boy is called a mad pash in Cheshire (see Grose in

Pash); which, as Henley remarks on the passage in Winter's Tale, is designed

to characterize him from the wantonness of a calf that blunders on, and runs

his head against anything.

Bat, s. a wooden tool used for battering or beating clods of earth.

To Bat, v.a. to strike with a bat.

Bath, s. a sow.

Beethy, adj. soft, sticky, contrary to crisp, overripe. It is also said of a

person in a slight perspiration. Grose in v. states that underdone meat is so

called in Herefordshire; but this sense is not known

b3

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7812) (tudalen 010)

|

]0 Provincial Words

at present. In Boucher's Glossary, to heath is explained to mean k< to dry

by exposure to the fire." To bathe is used by Chaucer, C. T. 15273, as equivalent

to bask. From these uses it may be inferred that beethy means such a degree

of moisture as is created in a porous substance by imperfect exposure to

heat, sufficient to cause the steam to pervade it, but not to drive it off

entirely.

To Bellrag, v. to scold in a clamorous manner. “To ballerag” has the same

meaning in the West Riding of Yorkshire; "to bullyrag" in Norfolk;

“to ballirag” in Devonshire and Somersetshire: Willan, Forby, Palmer, and

Jennings, invv. "To rag” is used in the North in the same sense: Grose

in v. Comp. Crav. Gl. in Bullyrag.

To Bellock, v. to bawl, to bellow. A cow which has lost her calf bellocks.

Formed, as well as bellow, from bellan, A.S. To bullock is used in Norfolk: Forby

in v.

Bent, s. the seed-stalk of grass. Hence the popular distich:

Pigeons never do know woe, But when they do a benting go.

That is, pigeons are never in want of food except at times when they are

reduced to the necessity of living on the seeds of the grass, which ripen

before the crops of grain. In Jennings's Somersetshire

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7813) (tudalen 011)

|

used in Herefordshire. 1 1

Glossary, "bennet'; is "long coarse grass," and "bennety,

abounding in bennets." In the Westmoreland and Cumberland Glossary, bent

grass is explained to be long coarse grass, which chiefly grows upon the

moors. See also Crav, Gl. and Forby in v. Bent is used in the old ballad of Chevy

Chace, —

el Bomen bickarte upon the bent, With their broad aras cleare."

Stanza 5.

and in the ballad of Sir Cauline, Part 1, st. 20, (Percy, vol. i.)

" Then a lightsome bugle heard he blow- Over the bents so brown."

It is remarkable that the word bent, as used in the old ballad of Chevy

Chace, to signify grass or field generally, was mistaken by the author of the

modern ballad to mean inclination of the mind. See Percy's Introduction to

the modern ballad, vol. ii. See further Boucher's Glossary in v. Bent is also

Scotch, and is used by W. Scott; e. g. in Thomas the Rhymer, Part 3.

•' But footsteps light across the bent The warrior's ears assail."

Bent is so called, because the seed-stalk of grass bends

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7814) (tudalen 012)

|

12 Provincial Words

with the wind. In Chancer, bent signifies the bending or declivity of a hill,

Tyrwhitt in v.

Bessy, s. “Don't be a bessy," said to a man who interferes with a

woman's affairs or business. (Forest of Dean.)

Besom, s. a birch broom. (In common use.) It is never applied to a bair

broom. Used in other parts of the country; Grose in Beesom and Besom.

To Bett, v.a. to pare the greensward with a breast-plough, or betting-iron,

usually with a view to its being burnt, and the ashes spread for manure. The

sod when so pared is called “the betting:" thus “setting up the

betting," “putting fire to the betting." The same process is known

in Devonshire and other parts of England by the name of • ' beat," or “burning-beat,"

or “beat-burning," according to Boucher in Beate burning, and Palmer in

Beat.

To "bete fires" is used in Chaucer for to prepare fires, C. T.

2255. 2294. In C. T. 3925, "to bete ,? means to mend; and in another

place to 64 bete sorwe '' is to heal sorrow. The original sense of the word

seems to be that of mending or setting to rights; connected with bet, bette,

(Chaucer, C. T. 7. r )33,) and better. It may tend to confirm the notion that

this is the original meaning of bete, if we consider that "bette,"

adj., meant fertile

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7815) (tudalen 013)

|

used in Herefordshire. 2 3

in old English. “Let the soil be as fertile and bette as any would

wish," quotation from Holinshed in note to Southey's Life of Wesley, ii.

p 594. Now on looking to u till “we find the

. general sense of preparing, setting in order, narrowed to the agricultural

meaning; and so it may have been with bete, bette, and beti.

Better, adv. more numerous. As, Ci better nor ten." See Craven Glossary,

in v.

To Bewray, v. to defile with ordure.” g The birds bewray the church." It

is used by old writers in the sense of discover or betray: see Junius, Nares,

and Tyrwhitt in v.

Bilberry, s. a small black bogberry, the wortleberry.

Black Poles, poles in a copse which have stood over one or two falls of

underwood.

Blob, s. a blister. Bleb \ and blob occur in the Craven Glossary, with the

sense of a bubble or blister. Blob is also Scotch; see Jamieson in Bleib and

Blob. In Suffolk, blob, according to Moor, signifies "a blunt

termination to a thing that is usually more pointed. A parrot's tongue is said

to be blob-indid, or to have a blob end. A person who, by biting his or her

nails, has injured the shape of the fingers, would be called blob-Jingered*

p. 35. See also Forby in v. The word blob is etymologically connected with

the Latin

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7816) (tudalen 014)

|

14 Provincial Words

bulbus, and other numerous words belonging to the same root, in which the

idea of roundness predominates. See the Philological Museum, vol. i. p. 405,

sqq.

Body, s. Used as a term of commiseration, to denote deficiency. As “A poor

simple body." “I never seed such a poor helpless body in my life; she

canna do nothing."

Body-horse, s. the second horse of a team of four. e. g. “Smiler was in the

body yesterday." (GL.)

Bogie, s. a ghost. Not peculiar to Herefordshire. See Junius in Bogie and

below in Bugabo.

Bolting, s. A “bolting of straw” is a quantity of straw tied up into a bundle

or small truss. When straw is sold by the weight, each bolting ought to weigh

14 lbs.; but boltings of straw are often bought and paid for according to

their apparent size. The word is also used in Gloucestershire. It is probably

derived from the peculiar -mode in which the band of straw is fastened down,

and, as it were belted, for the purpose of holding the truss together. See

Thrave. Pease-bolt is used for pease-straw in Essex: Grose in v.

To Boodge, v.a. to stuff bushes into a hedge. Probably a variety of to push.

Boosy, n. s. the manger of a cattle-stall. From Bosig or bosg, A.S. Bosworth

in v. Boose is ex-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7817) (tudalen 015)

|

used in Herefordshire.

it

plained by Johnson to mean “a stall for a cow

or an ox," but he gives no example of it in any writer. It is used in

Cheshire, according to Wilbraham, and in Yorkshire, according to the Craven

Glossary, and Hunter's Appendix, p. 119. See Junius in Boose.

Bottle, n. s. Sometimes used in the same sense as costrel, which see.

To be Bound, v. to be sure. “He is bound to be there," he is sure to be

there. Also used in Gloucestershire.

To Box, v. n. to strike, as a gun which recoils. The word box signifies a

blow, in the expression, M Box on the ear." It has the same sense in

Chaucer: Tyrwhitt in v.

Brad, n. s. a nail with a small head. This word is used in Cheshire: see

Wilbraham in v. Grose says, “Brod, a kind of nail, called brads in the south."

This word, though it occurs in other provincial glossaries, seems to be

generally used, and is inserted in Johnson's Dictionary.

Brags, s. u To make his brags" is to brag, to boast, to threaten to do

great things, in a presumptuous and confident manner; as, “He made his brags as

he would do for 'em all if he met them at the fair."

Brass, s. copper coins. “I paid him eleven pence:

|

|

|

|

|

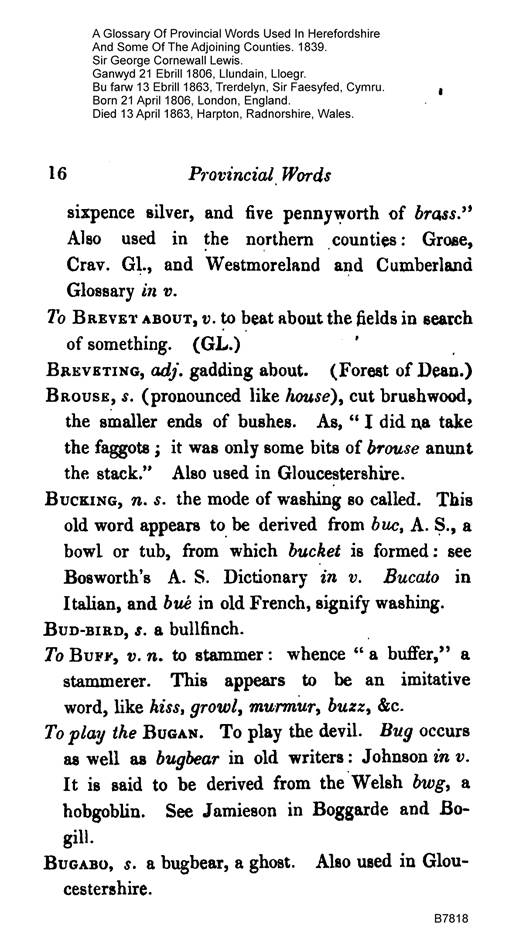

(delwedd B7818) (tudalen 016)

|

16 Provincial Words

sixpence silver, and five pennyworth of brass" Also used in the northern

counties: Grose, Crav. Gl., and Westmoreland and Cumberland Glossary in v.

To Brevet about, v. to beat about the fields in search of something. (GL.)

Breveting, adj. gadding about. (Forest of Dean.)

Brouse, s. (pronounced like house), cut brushwood, the smaller ends of

bushes. As, “I did na take the faggots; it was only some bits of brouse anunt

the stack.'* Also used in Gloucestershire.

Bucking, n. s. the mode of washing so called. This old word appears to be

derived from buc, A.S., a bowl or tub, from which bucket is formed: see Bosworth's

A.S. Dictionary in v. Bucato in Italian, and bu'e in old French, signify

washing.

Bud-bird, s. a bullfinch.

To Buff, v.n. to stammer: whence "a buffer," a stammerer. This

appears to be an imitative word, like hiss, growl, murmur, buzz, &c.

To play the Bugan. To play the devil. Bug occurs as well as bugbear in old

writers: Johnson zn v. It is said to be derived from the Welsh bwg, a hobgoblin.

See Jamieson in Boggarde and Bogill.

Bugabo, s. a bugbear, a ghost. Also used in Gloucestershire.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7819) (tudalen 017)

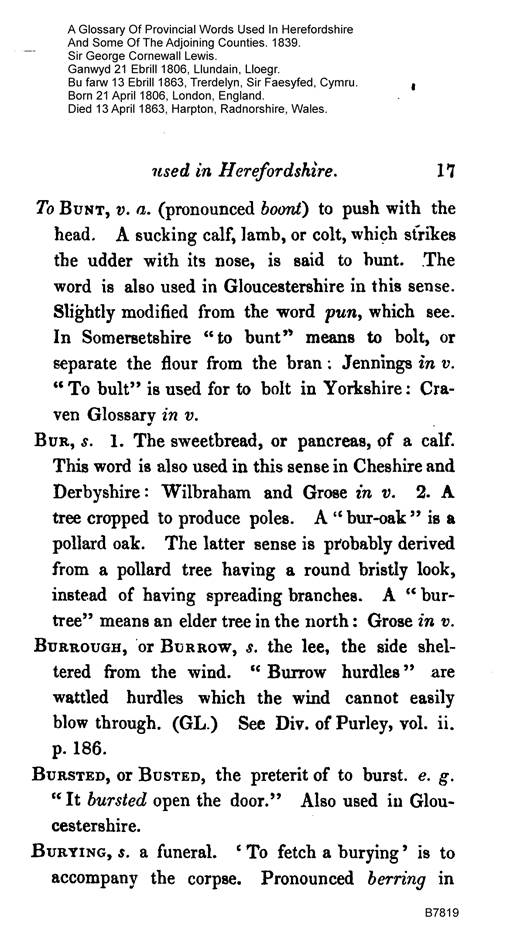

|

used in Herefordshire.

17

To Bunt, v.a. (pronounced boont) to push with

the head. A sucking calf, lamb, or colt, which strikes the udder with its

nose, is said to hunt. The word is also used in Gloucestershire in this

sense. Slightly modified from the word pun, which see. In Somersetshire

"to bunt" means to bolt, or separate the flour from the bran:

Jennings in v. “To bult" is used for to bolt in Yorkshire: Craven

Glossary in v.

Bur, s. 1. The sweetbread, or pancreas, of a calf. This word is also used in

this sense in Cheshire and Derbyshire: Wilbraham and Grose in v. 2. A tree

cropped to produce poles. A "bur-oak" is a pollard oak. The latter

sense is probably derived from a pollard tree having a round bristly look, instead

of having spreading branches. A “bur-tree" means an elder tree in the

north: Grose in v.

Burrough, or Burrow, s. the lee, the side sheltered from the wind. “Burrow

hurdles” are wattled hurdles which the wind cannot easily blow through. (GL.)

See Div. of Purley, vol. ii. p. 186.

Bursted, or Busted, the preterit of to burst, e. g. “It bursted open the

door." Also used in Gloucestershire.

Burying, $. a funeral. ' To fetch a burying ' is to accompany the corpse.

Pronounced berring in

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7820) (tudalen 018)

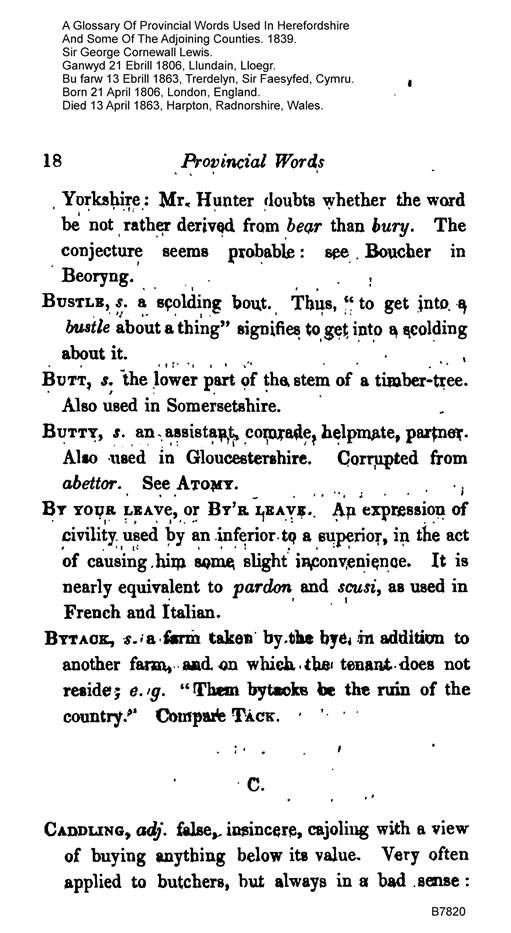

|

18 Provincial Words

Yorkshire: Mr. Hunter doubts whether the word

be not rather derived from bear than bury. The

conjecture seems probable: see Boucher in

Beoryng. Bustle, s. a scolding bout. Thus, “to get into a

bustle about a thing" signifies to get into a scolding

about it. Butt, s. the lower part of the stem of a timber-tree.

Also used in Somersetshire. Butty, s. an assistant, comrade, helpmate,

partner.

Also used in Gloucestershire. Corrupted from

abettor. See Atomy. By your LEAve, or By'r leave. An expression of

civility used by an inferior to a superior, in the act

of causing him some slight inconvenience. It is

nearly equivalent to pardon and scusi, as used in

French and Italian. Bytack, s. a farm taken by the bye, in addition to

another farm, and on which the tenant does not

reside; e. g. “Them bytacks be the ruin of the

country.'' Compare Tack.

C.

Caddling, adj. false, insincere, cajoling with

a view of buying anything below its value. Very often applied to butchers,

but always in a bad sense:

|

|

|

|

|

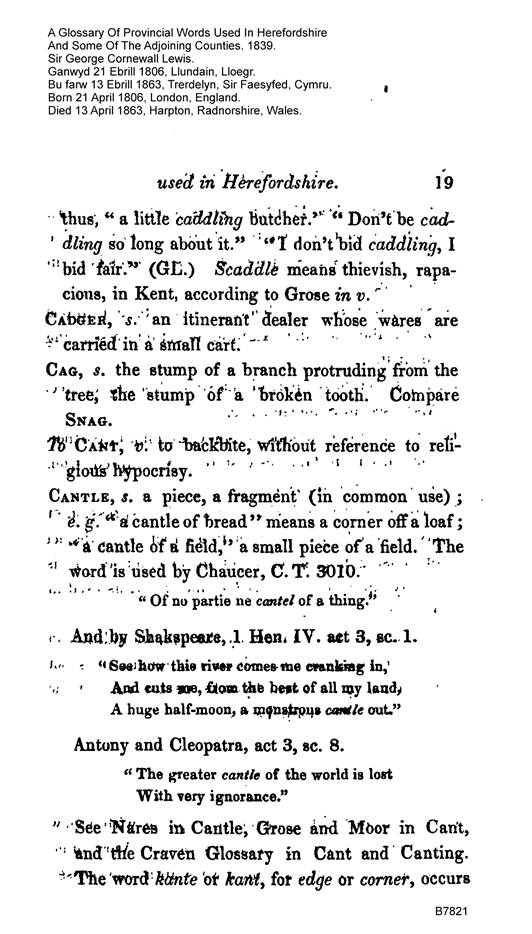

(delwedd B7821) (tudalen 019)

|

used in Herefordshire, \ 9

thus, “a little caddling butcher." "Don't be caddling so long about

it." “I don't bid caddling, I bid fair." (GL.) Scaddle means

thievish, rapacious, in Kent, according to Grose in v. Cadger, s. an

itinerant dealer whose wares are

carried in a small cart. Cag, s. the stump of a branch protruding from the tree,

the stump of a broken tooth. Compare Snag. To Cant, v. to backbite, without

reference to religious hypocrisy. Cantle, s. a piece, a fragment (in common

use); e. g. u a cantle of bread" means a corner off a loaf; *' a cantle

of a field," a small piece of a field. The word is used by Chaucer, C.

T. 3010.

" Of no partie ne cantel of a thing."

And by Shakspeare, 1 Hen. IV. act 3, sc. 1.

" See how this river comes me cranking in, And cuts me, from the best of

all my land, A huge half-moon, a monstrous cantle out."

Antony and Cleopatra, act 3, sc. 8.

si The greater cantle of the world is lost With very ignorance."

See Nares in Cantle, Grose and Moor in Cant, and the Craven Glossary in Cant

and Canting. The word kante or kant, for edge or corner, occurs

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7822) (tudalen 020)

|

20 Provincial Words

in nearly all the Teutonic languages. See Meidinger's Compar. Dictionary, p.

193.

Candle of the Eye, s. pupil of the eye. In Norfolk and Suffolk the pupil of

the eye is called the “bird of the eye;" Grose and For by in v., in

which expression "bird" means damsel, or girl, (see Jamieson in v.)

and is equivalent to Kopiy in Greek and pupil la in Latin. The name is

derived from the diminished image of himself which the beholder sees iu the

eye of the person whom he addresses. See Boucher in “Bird of the eye."

Carlock, s. the weed charlock.

Cauve, s. calf.

Char, or Cher, s. a job. “To do a char (or chair) for a friend," is to

do a job for a friend. u That's a good cher," that is a good job;

expressive of approbation. Also used in Gloucestershire. See Nares in Chare.

In Devonshire and Somersetshire this- word is pronounced choor. See Jennings in

Choor, Palmer in Chures. See Tooke's Div. of Purley, vol. ii. p. 192.

Charks, s. charcoal.

To Chark, v. to make charcoal, to char.

A Charker, s. one who makes charcoal.

To Chastise, v. to question closely, particularly as to some mischief done. A

similar confusion of examination and punishment occurs in the line of

used in Herefordshire.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7823) (tudalen 021)

|

21

Virgil, “Castigatque, auditque dolos,

subigitque fateri." Mn. vi. Chats, s. dead sticks. According to Grose's

Glossary, “chat " means “a small twig " in Derbyshire; “chats"

means “keys of .trees, as ash-chats, sycamore-chats," in the northern

counties; and “chattocks" means "refuse wood, left in making 4

faggots," in Gloucestershire. According to the present usage in

Gloucestershire, the chips which fly from the axe when a tree is cut down are

called chats; what the carpenter cuts off, chips, “Chats " is explained

to mean spray- wood in the Westmoreland and Cumberland Glossary. According to

the Craven Glossary, "chatts-" are “the capsules of the ash,

sycamore, &c, called also keys" According to Moor's Suffolk Words, “chates,"

or “chaits," are “broken victuals; the remnants of turnips or other food

left by fatting sheep, &c, to which leaner or more hungry stock is turned

in, to pick up the chaits, or orts." “Chats," or “chatter bushes,"

are explained by Moor to be “protruding bushes of blackthorn, &c, running

into a field from the fence; or the lower straggling branches of a tree,

which we otherwise call sprawls" Forby, in v., says that chaits is the

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7824) (tudalen 022)

|

22 Provincial Words

same word as chits, whence the diminutive chitterlings. In German, katze has

the sense of a bundle or bunch; and it also signifies the keys of a tree. See

Adelung in Katze, No. 5. The English word catkins is a cognate form.

Chawm, s. a crack in the ground caused by dry weather. Corrupted from chasm.

(GL.)

Cheese, s. Cider hairs filled with must aud piled in readiness to be pressed.

A various form of case. It may be observed that the Italian formaggio is derived

from forma, in the sense of a case, i. e. the case in which the cheese is

pressed.

Chilver, s. an ewe lamb. (GL.) Grose explains it to mean “the mutton of a

maiden sheep."

Chimbley, s. chimney. This pronunciation of the w r ord is mentioned in the

Craven Glossary, in Wilbraham's Cheshire Glossary, in Jennings's

Somersetshire Glossary, in Palmer's Devonshire Glossary, and in Forby's East

Anglian Vocabulary. It is also usual in Gloucestershire. The insertion of b

after m occurs likewise in homber and sumber in this glossary: see further,

Lewis's Essay on the Romance Languages, p. 19, and Donaldson's New Cratylus,

p. 292. Sometimes the provincial dialect omits the b after m: thus the

Somersetshire dialect has timmer for timber (Zimmer, German), and

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7825) (tudalen 023)

|

used in Herefordshire.

23

the Somersetshire and Devonshire dialects have

emmers and yammers for embers: Jennings and Palmer in v. Compare Boucher in

Aymers.

Chump, s. a log of wood for burning. The thick end of a sirloin of beef is

called the ' chump end.' This word is also used in Gloucestershire and in Norfolk:

Forby in v.

Churm, s. a churn.

To Clam, v.a. I. to clog up, 2. to starve. In Gloucestershire u to clam"

means to stick or adhere, as clay or the like, so as to hinder work. If clay

or earth sticks to the spade, so that a man cannot dig, he is said to be ' c

clammed up." This old word (Nares in Clem) is still current in the north

of England. See Willan in Clam, Craven Glossary in Clam and Clammed, and

Wilbraham's Cheshire Glossary in Clem. In Suffolk the word is stated to be nearly

obsolete; see Moor in Clammd. But see Forby in v. It does not occur in

Jennings's Somersetshire Glossary; and in Palmer's Devonshire Glossary, “to

clum" or “clam" is explained, "to rumple or soil by handling,

from clumian, Sax., to daub, foul, or besmear." From “to clam," in

the sense of "to stick," is derived the adjective clammy,

Clea, s. claw. Each division of the hoof of an ox or other cloven-footed

animal is called a clea. This

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7826) (tudalen 024)

|

24 Provincial Words

form is used in Yorkshire, Cheshire, and Norfolk: Craven Glossary, Wilbraham

and Forby in v.

Cleaching Net, s. a bag-net, attached to a semi-circular hoop having a

transverse piece, to the centre of which a pole is fixed. The net is put gently

into the stream, and drawn towards the bank when the river is in flood, and

the fish draw to the sides. Called a clinching-net in Gloucestershire.

To Cleach, v. to use a cleaching net.

Cockshut, s. a contrivance for catching woodcocks in an open glade or drive

in a wood, by means of a suspended net. In some places, cockshut, from an

appellative, has become a proper name, the meaning being extinct.

To Collogue, v. n. to converse together (used in a bad sense). See Nares,

Hunter, Craven Glossary, Forby, Moor, and Jennings, in v.

Colly, adj. dirty, smutty, from coal. See Nares in Colly and To Colly,

Wilbraham's Cheshire Gloss. in Collow. Steevens on “Othello," act 2, sc.

3, (" Passion having my best judgment collied,") states that the

word colly was used in the midland counties in his time. In Gloucestershire,

according to Grose, colley means the black or soot from a kettle. In

Somersetshire, a colley, according to Jennings, means a blackbird.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7827) (tudalen 025)

|

used in Herefordshire. 25

To Come, v. applied to the increase of a river in flood, as “Wye's a

coming."

Come by now, used as an exclamation for "get out of the way."

To Come down upon, v. to reprove, to chide. The same as to “get over."

Comical, adj. ill-tempered. See Stick.

Out of the common, out of the common way.

To Conceit, v. and Conceit, s. (sometimes pronounced consate.) To suppose, a

notion, as u I conceited it was so;" “I had no conceit of it."

To Concern with, v. n. to meddle with.

Cop, s. The “cop of a ridge" is the summit of a ridge in a ploughed

field; compare re en. Cop signifies a top or summit in Welsh; but the word occurs

in all the Teutonic languages, and it is doubtful whether its use in

Herefordshire was derived from the Welsh. See Grose in Cop and Cope.

Coppy, s. a coppice; so called, according to Willan in v., as being a round

woody eminence, from cop.

Cornel, .9. a corner.

Costrel, s. a small portable cask, used for carrying beer or cider into the

field. This word is in the Craven Glossary, and Grose calls it a north country

word. It may probably occur as a provin-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7828) (tudalen 026)

|

26 Provincial Words

cialism in other parts of the kingdom; for its usage

is ancient. Costrellus occurs in Matthew Paris;

see Ducange in v. Costeret or cousterei is used in

old French, in the sense of a measure for wine or

other liquors; Roquefort in vv. This form of the

word occurs in the Romance of Richard Cceur de

Lion:

* Now, steward, I warne thee Buy us vessel [i. e. vaisselle] great plente. Dishes,

cuppes, and saucers, Bowls, trays, and platters, Vats, tuns, and costret; Maketh

our meat withouten let."

Ellis's Romances, vol. ii. p. 213.

Costrel is used by Chaucer, Legend of Goode Women, 2655. A costrel is

probably so called from being made of costce, staves or ribs hooped together.

To Couch, v. n. to squat, to sit as a rabbit or hare. From the French

coucher.

To Cowse, v. to chase animals, particularly sheep and pigs. It may also be

said of an idle person, that he “goes tampering and cowsing about." Probably

a corruption of to course.

Cowt, s. a colt.

Cratch, s. a rack for hay in a stable. Cratch is also used in other counties:

Grose, Moor, and Hunter in v. An old word: thus Spenser, Hymn

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7829) (tudalen 027)

|

used in Herefordshire. 2?

of Heav. Love, st. 33.

" Begin from first, where he encradled was In simple cratch, wrapped in

a wad of hay."

See also Nares in Cratch. Cratch and rack are probably different forms of the

same word.

Craven, s. (pronounced cravven), a coward. In common use.

Crink, s. a very ^small child. In Gloucestershire, according to Grose, a

crinch means a small bit.

To Crowdle, v. n. to crouch. “Crowdled up" is bent or doubled up, like a

sick animal: from to crowd. This word has a nearly similar sense in Yorkshire,

Cheshire, Devonshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk. See Craven Glossary in Cruddle,

Wilbraham and Moor in Crewdle, Forby, Grose, and Hunter in Croodle, Palmer in

Crudle.

Cue, s. a coop, hatch, kennel. A variety of coop

Cue (or Kew), s. an ox's shoe. Also used in Gloucestershire.

To Cue (or Kew), v. to fasten shoes on the feet of oxen. An old man resided

many years ago at Michel Dean, in Gloucestershire, who was known by the name

of the Ox-cuer, from his dexterity in this business, which requires skill and

care, inasmuch as it is necessary that the animal should be thrown. The word

ox-kew appears to have been originally ox-skew, and to have been derived from

c 2

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7830) (tudalen 028)

|

28 Provincial Words

the oblique or crooked form of the iron plate which was attached to each

division of the ox's hoof. The absorption of the initial 5 after a final x

would, upon this supposition, be analogous to the corruptions explained under

the word Atomy.

To Curf potatoes, is to earth them up. From to cover.

Curious, adj. strange; as "a curious temper." The adjectives,

comical, curious, and ridiculous, imply blame.

Curst, adj. ill-tempered, cross-grained; applied both to men and animals. An

ancient usage; see Nares in v.

Cute, or Cude, adj. sharp, acrimonious, corrupted from acute. Also used in

Cheshire: Wilbraham in v.

Cutwith, s. the bar of the plough to which the traces are attached. Compare

Lantree.

D.

Daddock, s. dead wood, touchwood; in Gloucestershire, dead wood is said to be

“daddocky," or “all of a daddock." In Somersetshire, according to Jennings,

“daddick" is rotten wood, and “dad-dicky" is rotten. According to

Grose, dadacky means tasteless in the western counties. Daddock

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7831) (tudalen 029)

|

used in Herefordshire. 29

has been derived from dead-oak; but the termination is probably similar to

that in bullock, paddock, mammocks, and other words. See Philol. Museum, vol.

i. p. 685. Daffish, adj. shy, embarrassed, easily abashed. Daftish has the

same sense in the Craven Glossary. Grose has to daffe, to daunt, as a north country

word. “To daff" is to confound, in the West Riding, according to Willan

in v. DafTe signifies a fool in Chaucer, C. T. 4206.

" I shall be holden a daffe or a cokeney."

The Scotch daft is evidently the passive participle of to daff. Dar, s. a

mark, as a mark set up in a field to measure by. “How did you measure it?"

— “I did stick up my stick as a dar." In Chaucer, to dare, is to stare:

" That lie and dare As in a form sitteth a wery hare." — C. T.

13,033.

Thus dar may mean a thing stared at; as we call

a colour a “staring colour," which attracts notice. Dandering, part,

twaddling. See Wilbraham in

Dander. Dank, adj. damp; also used in Gloucestershire. It

is pronounced donk in the north. Crav. Gloss.

|

|

|

|

|

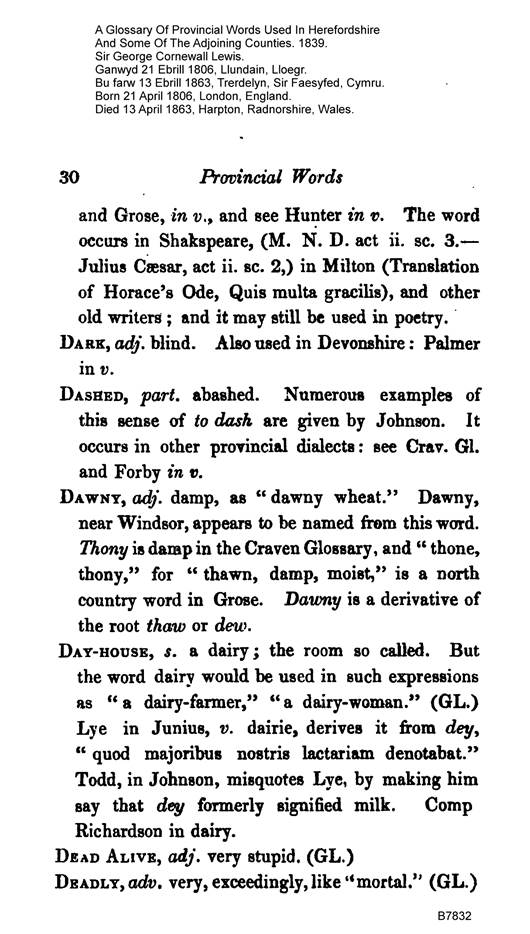

(delwedd B7832) (tudalen 030)

|

30 Provincial Words

and Grose, in v. 9 and see Hunter in v. The word occurs in Shakspeare, (M. N.

D. act ii. sc. 3. — Julius Caesar, act ii. sc. 2,) in Milton (Translation of

Horace's Ode, Quis multa gracilis), and other old writers; and it may still

be used in poetry.

Dark, adj. blind. Also used in Devonshire: Palmer in v.

Dashed, part, abashed. Numerous examples of this sense of to dash are given

by Johnson. It occurs in other provincial dialects: see Crav. Gl. and Forby

in v.

Dawny, adj. damp, as “dawny wheat." Dawny, near Windsor, appears to be

named from this word. Thony is damp in the Craven Glossary, and “thone, thony,"

for “thawn, damp, moist," is a north country word in Grose. Dawny is a

derivative of the root thaw or dew.

Day-house, s. a dairy; the room so called. But the word dairy would be used

in such expressions as "a dairy-farmer," "a dairy-woman."

(GL.) Lye in Junius, v. dairie, derives it from dey y “quod majoribus nostris

lactariam denotabat." Todd, in Johnson, misquotes Lye, by making him say

that dey formerly signified milk. Comp Richardson in dairy.

Dead Alive, adj. very stupid. (GL.)

Deadly, adv. very, exceedingly, like "mortal. " (GL.)

|

|

|

|

|

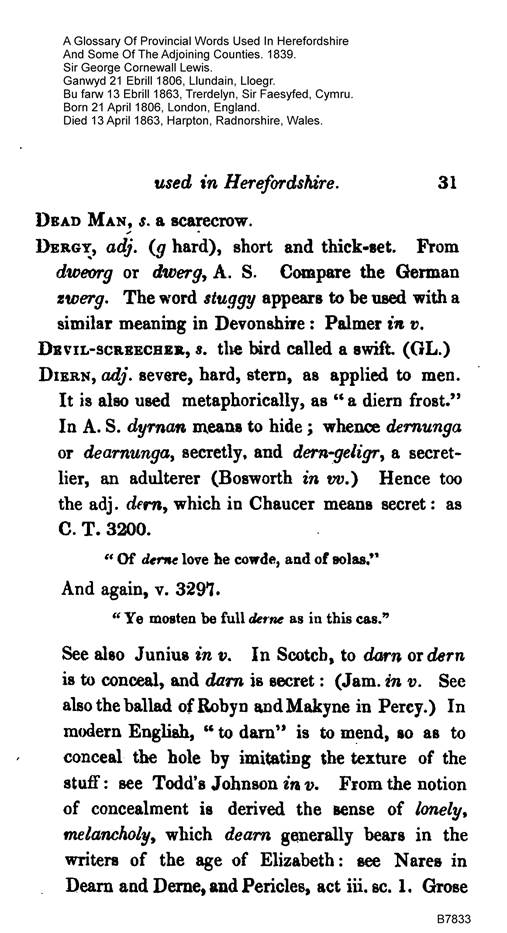

(delwedd B7833) (tudalen 031)

|

used in Herefordshire. 31

Dead Man, s. a scarecrow.

Dergy, adj. (g hard), short and thick-set. From dweorg or diver g, A.S.

Compare the German zwerg. The word stuggy appears to be used with a similar

meaning in Devonshire: Palmer in v.

Devil-screecher, s. the bird called a swift. (GL.)

Diern, adj. severe, hard, stern, as applied to men. It is also used

metaphorically, as “a diern frost." In A.S. dyrnan means to hide; whence

dernunga or dearnunga, secretly, and dern-geligr, a secretlier, an adulterer

(Bosworth in vv.) Hence too the adj. dem y which in Chaucer means secret: as C.

T. 3200.

" Of derne love he cowde, and of solas." And again, v. 3297.

" Ye mosten be full derne as in this cas."

See also Junius in v. In Scotch, to darn or dern is to conceal, and darn is

secret: (Jam. in v. See also the ballad of Robyn andMakyne in Percy.) In modern

English, “to darn" is to mend, so as to conceal the hole by imitating

the texture of the stuff: see Todd's Johnson in v. From the notion of

concealment is derived the sense of lonely, melancholy, which dearn generally

bears in the writers of the age of Elizabeth: see Nares in Dearn and Derne,

and Pericles, act iii. sc. 1. Grose

|

|

|

|

|

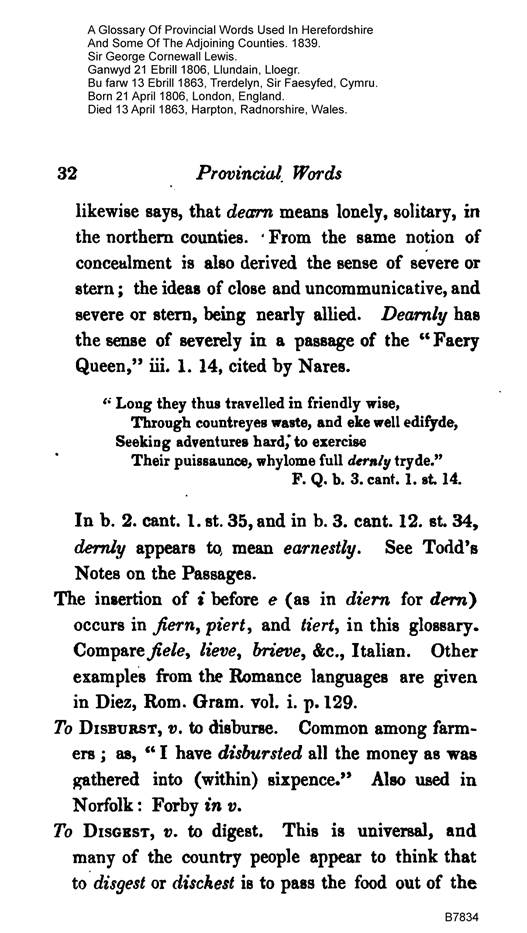

(delwedd B7834) (tudalen 032)

|

32 Provincial Words

likewise says, that decern means lonely, solitary, in the northern counties.

From the same notion of concealment is also derived the sense of severe or stern;

the ideas of close and uncommunicative, and severe or stern, being nearly allied.

Dearnly has the sense of severely in a passage of the “Faery Queen," iiL

1. 14, cited by Nares.

<• Long they thus travelled in friendly wise,

Through countreyes waste, and eke well edifyde, Seeking adventures hard, to

exercise

Their puissaunce, whylome full dernly tryde."

F. Q. b. 3. cant. 1. st. 14.

In b. 2. cant. 1. st. 35, and in b. 3. cant. 12. st. 34, dernly appears to

mean earnestly. See Todd's Notes on the Passages.

The insertion of i before e (as in diem for dern) occurs in fiern, piert, and

tiert, in this glossary. Compare Jiele, lieve, brieve, &c, Italian. Other

examples from the Romance languages are given in Diez, Rom. Gram. vol. i. p.

129.

To Disburst, v. to disburse. Common among farmers; as, “I have disbursted all

the money as was gathered into (within) sixpence." Also used in Norfolk:

Forby in v.

To Disgest, v. to digest. This is universal, and many of the country people

appear to think that to disgest or dischest is to pass the food out of the

|

|

|

|

|

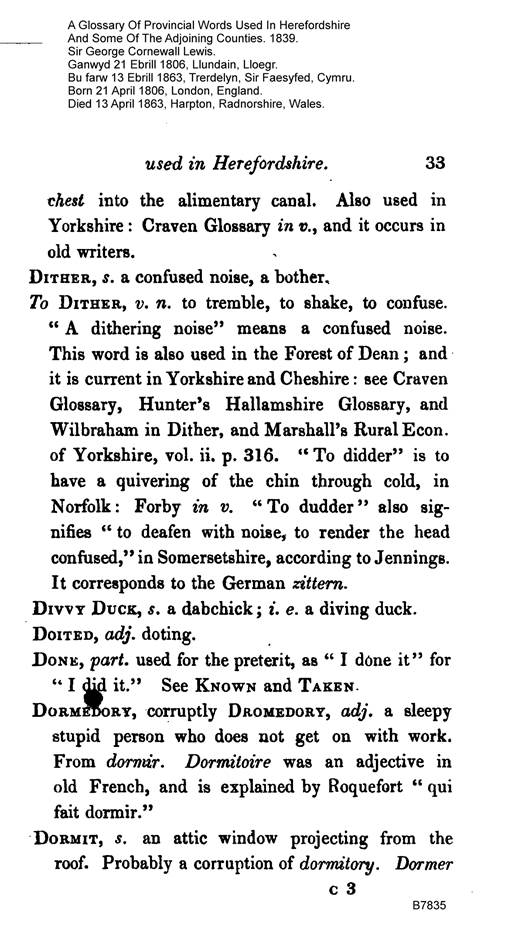

(delwedd B7835) (tudalen 033)

|

used in Herefordshire. 33

chest into the alimentary canal. Also used in Yorkshire: Craven Glossary in

v., and it occurs in old writers.

Dither, s. a confused noise, a bother.

To Dither, v. n. to tremble, to shake, to confuse. “A dithering noise"

means a confused noise. This word is also used in the Forest of Dean; and it

is current in Yorkshire and Cheshire: see Craven Glossary, Hunter's

Hallamshire Glossary, and Wilbraham in Dither, and Marshall's Rural Econ. of

Yorkshire, vol. ii. p. 316. “To didder" is to have a quivering of the

chin through cold, in Norfolk: Forby in v. “To dudder " also signifies “to

deafen with noise, to render the head confused," in Somersetshire,

according to Jennings. It corresponds to the German zittern.

Divvy Duck, s. a dabchick; i. e. a diving duck.

Doited, adj. doting.

Done, part, used for the preterit, as “I done it" for “1 did it."

See Known and Taken.

Dormedory, corruptly Dromedory, adj. a sleepy stupid person who does not get

on with work. From dormir. Dormitoire was an adjective in old French, and is

explained by Roquefort “qui fait dormir."

Dormit, s. an attic window projecting from the roof. Probably a corruption of

dormitory. Dormer

c 3

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7836) (tudalen 034)

|

34 Provincial fiords

means a large beam in Norfolk: Forby in v. The latter word may perhaps be

compared with sleeper, which Grose explains to be a “baulk or summer supporting

a floor." The use of the latter word has lately become familiar from its

being applied to the supports of the rails on railways.

Doust, s. dust. Dousty, adj. dusty. Dousting, s. dusting. (GL.)

To Dout, v.a. to put out, as a candle. “He is just douted," — he is just

dead. Also used in Gloucestershire.

Drag, s. a fence placed across running water, consisting of a kind of hurdle

which swings on hinges, fastened to a horizontal pole.

To Dreaten, v. to threaten.

To Dresh, v. to thrash. Also used in Gloucestershire. Pronounced drash in

Devonshire and Somersetshire: Palmer and Jennings in v.

To Drive a Boat, to propel a boat with a pole or paddle.

To Drop out, v. to fall out, to quarrel. (GL.)

Droughty, adj. (pronounced drufty), thirsty; from drought.

To Drow, v. to throw.

Droxy, adj. the same as daddocky, which see. (GL.)

Duberous, adj. doubtful. Also used in Devonshire, Palmer in v.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7837) (tudalen 035)

|

used in Herefordshire. 35

Duff, adv. to fall duff, to fall heavily. Dufian, A.S. is to sink (Bosworth

in v.) Perhaps that which falls as if it would sink to the bottom falls duff.

See H. Tooke, i. 419.

Dunny, adj. hard of hearing. See Jamieson in Donnar and Donnard. Dunch is

deaf in the Gloucestershire and also the Somersetshire dialect; whence (and

not from Duns Scotus), as Jennings observes, is derived the word dunce.

Compare Adelung in Donner. Dull means hard of hearing in Somersetshire and

Yorkshire, according to Grose and Crav. Gl.

To Dup, v. to do up, to fasten. (GL.) In Hamlet, act 4. sc. 5. it means to

open, probably from raising the latch.

" Then up he rose and donned his clothes. And dupp'd the chamber

door."'

Dyche, 5. a mound, a dyke, the bank of a hedge. Dyson, *. the flax, &c.,

on a distaff. This word

appears to be connected with the first syllable of

distaff.

E.

Elder, s. udder. The use of this word extends to Gloucestershire and

Worcestershire, and it also occurs in Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire.

See Craven Glossary, Hunter, and Wilbraham in v.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7838) (tudalen 036)

|

36 Provincial Words

Ellern Tree, or Ellern Aul, s. an elder tree. The elder is called eller in

Yorkshire and Cheshire: Craven Glossary, and Wilbraham in v. The older adjectival

form of el lam or ellern (used in Piers Ploughman's Vision) is preserved in

Herefordshire, as it also is in Norfolk: Forby in Eldern.

Elmen, adj. from elm. “Elmen tree," is elm tree. Used also in

Somersetshire: Jennings in v. Compare Aulen, Ellern-tree, Poplern, and

Tinnen, in this Glossary, which adjectives are formed like oaken, ashen,

treen, golden, &c. Dirten and hornen are used in Somersetshire: Jennings

in v.

To Empt, v.a. to empty. This verb is also in Jennings's Somersetshire

Glossary.

Etherings, s. long rods twisted at the top of a hedge. Edderings and eder are

used in Cheshire, Wilbraham in v.; and ether in Yorkshire, Essex, and Norfolk:

Craven Glossary in v. and in Yether, Forby in Ether, Grose in Edder. Eder, edor,

or efSor is a hedge in A.S. (Bosworth in v.), and consequently etherings is a

word regularly formed, and means hedgings, or materials for hedging.

Ettles, or Ettle^s, s. nettles. Also used in Gloucestershire. The common form

is the correct one: netele A.S. (see Bosworth in v.), nessel H. German.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7839) (tudalen 037)

|

used in Herefordshire. 37

F.

Fagget, s. an “old fagget " is a term of

reproach to emaciated old people, equivalent to the familiar expressions, u a

bundle, or bag, of bones." In Gloucestershire, to call a woman an old

faggot is almost the greatest insult that can be offered to her. Also used in

Norfolk: Forby in v.

Fainty, adj. faint.

To Fall, v.a. to throw down. As, “she fell the child." Also 4t to fall a

tree." Compare to*Rise. Also used in Norfolk: Forby in v.

Fancical, adj. fanciful.

Fatch, v. and s. thatch.

Fatches, s. vetches.

Fat-hen, s. a weed so called.

To Fault, v.a. to find fault with. “I don't fault him for that."

Featherfold, s. the herb feverfew.

To Fear, v.a. to frighten. See Nares in v., and compare afeard.

Feast, s. a day of merry-making for the country-people. Each village has its

feast, which occurs on a fixed day in every year. The use of this word in

Herefordshire exactly resembles that described by Mr. Hunter in his

Hallamshire Glossary.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7840) (tudalen 038)

|

3S Provincial Words

To Feed, v. n. to grow fat. Also used in the northern counties, Grose in v.

Feg, s. grass which has withered upon the ground, without being severed from

its root. Fog is used in a similar sense in Cheshire, Yorkshire, and other

northern counties; and also in Norfolk and Suffolk. See Grose, Willan, Craven

Glossary, Moor, and Forby in v. Feg is used in Worcestershire. According to

Thoresby and Watson in Hunter's Appendix, p. Ill, 146, fog in Yorkshire means

aftergrass.

Fellom, s. a whitlow. The word "fellon" is cited in Nares's

Glossary, with the sense of “a boil or whitlow," from writers of the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Fellom, however, is probably the more

correct form of the word, having arisen, by mispronunciation, from film. Film

signifies a tiiin skin, and is sometimes applied to the morbid skin which

covers an ulcer; thus in Hamlet: —

"It will but skin andjilm the ulcerous place, While rank corruption,

mining all within. Infects unseen." — Act 3, sc. 4.

The letter m does not combine easily with another consonant at the end of a

syllable; and in several words where this combination occurs, a vowel has been

interpolated before m, in order to assist the pronunciation. Thus the A.S.

besm and bosm

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7841) (tudalen 039)

|

used in Herefordshire. 39

have, in modern English, become besom and bosom > and the A.S. word

hearmsceare (Grimm, Deutsche Rechtsalterthumer, p. 681) has been corrupted into

harumscarum. So chrism (from chrisma) was corrupted into chrisom and kirsom

(Nares, in vv.), and alarm into alarum. The Cornish and Devonshire word pilm,

which signifies dust, is pronounced pi/am or pillum (Grose and Palmer in v.).

The Cheshire word rism is also pronounced risom ( Wilbr. in v.); and the word

baron (in the expression “baron of beef") is derived from an older form,

birn (Crav. Gloss, in v.). In like manner, in Italian, chrisma, baptisma, and

spasma, became cresima, battesimo, and spasimo. If the words sarcasm, schism,

and chasm had become popular in English, their pronunciation would probably

have been changed. (See above in Chawm.) Where / or r follows a and precedes

m, the vowel is lengthened, and the following consonant is suppressed in

pronunciation: thus psalm, balm, calm, farm, harm, are pronounced sdm, bam, cam,

fdm 9 ham. The word film is probably connected with the English and German

fell. In Yorkshire, the word fellon signifies a disease in cows: see Craven

Glossary in v.

Fellow, s. a young unmarried man.

To Fettle, v.a. to settle, arrange, put in order. This

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7842) (tudalen 040)

|

40 Provincial Words

word is also used in Cumberland, Westmoreland, Yorkshire, and Cheshire:

Cumberland and Westmoreland Glossary, Grose, Willan, Craven Glossary, and

Wilbraham in v.; and compare Nares in v. The word fettle occurs three times

in the ballad of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, in Percy, vol. i.

Field, s. a ploughed field as distinguished from grass ground. (GL.)

Fiern, s. fern. Compare Diern.

Fiern-owl, s. a goat-sucker.

Fildefare, s. a fieldfare. This word is similarly pronounced in Somersetshire:

Jennings in v. In Gloucestershire it is sometimes pronounced vildever.

Filler, or Viller, s. the shaft horse of a cart or wagon. (GL.) Also used in

Norfolk: Forby in v.

Filthy, adj. In Gloucestershire this word is used in only two senses, viz.,

for a field full of weeds, especially couch grass, and for a person who has lice

on his body.

Filtry, or Viltry, s. trumpery, filth. Particularly applied to weeds in a

field or garden. (GL.) Also used in Somersetshire: Jennings in v. Another

form of Jilt h.

Fimble, s. a wattled chimney.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7843) (tudalen 041)

|

used in Herefordshire. 41

To Find, v. to stand sponsor to a child.

To Finegue, v. to avoid or evade a thing.

To Firm, v. to affirm. So in Somersetshire, to frunt is used for to affront:

Jennings in v. Compare Abundation.

Fitchuck, s. a pole-cat. Called Jitcher or fitchet in Gloucestershire. See

Grose in Fitchet and Fitchole, and Nares in Fytehock.

Flannen, Si flannel. Pronounced vlannin in Somersetshire, and Jtannin in

Devonshire: Jennings and Palmer in v.

Flat, s. a hollow in a field. (GL.)

Flath, s. dirt, filth, ordure.

Fleak, or Flake, s. a hurdle. This word is also used in Yorkshire: Hunter in

Flake, Crav. Gloss, in Fleeok, Grose in Fleake. So called from being interwoven:

compare the German Jlechten, Adelung in v.

To Flee, v. to fly; as “the rooks fled away," for flew away.

Flitchen, s. a flitcher of bacon.

Flummock, s. a slovenly person. Also used in Gloucestershire. ”Flammakin

" is a blowsy slatternly wench, in Devonshire, according to Palmer in v.

To Flummocks, v.a. to maul, to mangle.

Fought, part, of to fetch, . Also used in Gloucestershire and other counties.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7844) (tudalen 042)

|

42 Provincial Words

Frany, adj. violent tempered. From phrenzied.

Fresh liquor, hog's lard without salt in it. (GL.)

To Fret, v. n. Cider, when fermenting, is said to fret.

Fretchet, adj. fretful, peevish; or hot, fidgety (of a horse): from fret.

Fritful, or Frightful, adj. fearful, timorous.

Frum, adj. 1. early. From the A.S. frum, which means original, primitive.

Frum-bearn is first born. In Cheshire and Lancashire, frim signifies “tender

or brittle" (Wilbr. in v.), which is probably the same word. 2. Numerous,

thick. In Gloucestershire, frum means thick and strong, as mowing grass. In

Oxfordshire, its meaning is rank, overgrown. Frim, in the north, means handsome,

rank, well-living, in good case, according to Grose. From the A.S. from,

which means stout, strong, bold. Fromm, in high German, had originally the

same meaning; “ein frumer schlach," was equivalent to "ein heftiger

schlag;" "ein frommer Ritter:" Adelung in v. The two distinct

words frum and from are now confounded together, as the English word light

corresponds to the German licht and leicht. The name of the Fromey, a stream

in Herefordshire, appears to be connected with the latter sense of the word

in question. It is thus described in Leland's Itinerary,

used in Herefordshire. 43

vol. v. p. 12. " Fromey, a big broke, sumtyme raging, cummetli by

Bromyard, as I remembre, and so into Lug; and about it be very good

pastures"

Fuel, s. garden stuff.

Fund, Funded, part, found.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7845) (tudalen 043)

|

G.

Gadaman, adj. roguish.

To Gale, v. In the Forest of Dean, to gale (i. e. to gavel) a mine is to

acquire the right to work a mine from the officer called a gaveller, and to

pay the share of the crown.

Gall, or Gaul, s. a place where water breaks out on the land. Compare Soak.

Gally, adj. wet, as applied to land. In Yorkshire, a gall means a spring or

wet place in a field, and gaily means spungy, wet; Crav. Gloss, in v. In Norfolk,

a gall is a vein of sand in a stiff soil, through which water is drained off,

and oozes at soft places on the surface; otherwise sandgalls: Forby in v. See

also Grose in galls, gally-lands, and sandgalls. Galle has the very same

meaning in German: " Nasse stellen auf den ackern, besonders wenn sie

von kleinen quellen herkommen," says Adelung in v.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7846) (tudalen 044)

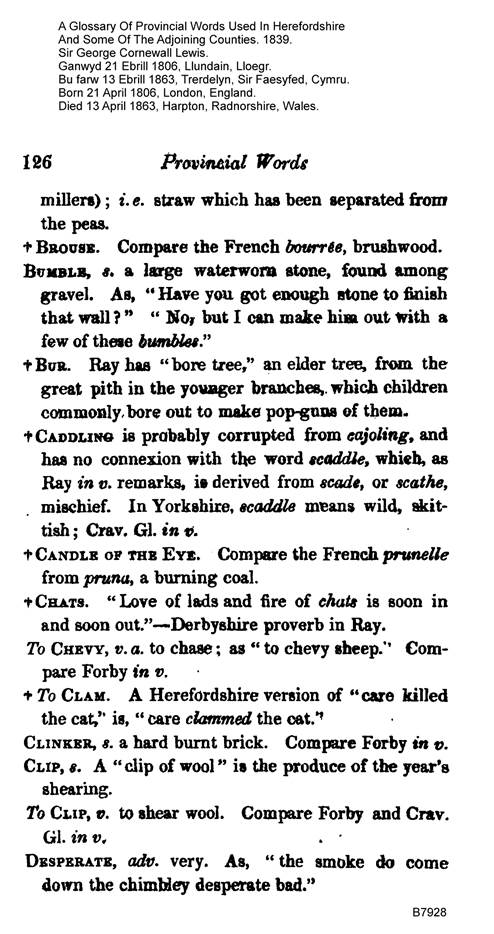

|

44 Provincial Words

Gally-team, s. a team kept for hire.

Gallier (or Hallier), s. one who keeps teams for hire. From to haul.

Gambrel, s. a cart with rails or thripples. In Suffolk, according to Moor, a

" gambrel " is " the crooked piece of wood on which the

carcases of slaughtered beasts, hogs, and sheep are expanded and suspended.

" The word is similarly explained by Jennings in v. In Devonshire,

" gammerells," or " gambrils " means not only a butcher's

stretcher, but also the hocks or lower hams of an animal: Palmer in v.

Gambrel probably meant originally a piece of crooked wood; and was derived

from the word which appears in different languages under the form hamme, ham,

gamba, emdjambe. Thus shipwrights speak of knees in ship-building. In like

manner, the handle of a scythe is called hamme and hammen in Switzerland;

Stalder, Schweiz. Idiot, in v. Hames (see below) has probably the same

origin. Cammed is explained crooked, in the Westmoreland and Cumberland Glossary.

In Welsh, too, camm or gam is crooked; it also means one-eyed, whence the

name of Sir David Gam. This use of the word is analogous to the Spanish

tuerto from tortus; " mas vale tuerto que ciego." See likewise

Crav. Gl. in Cammerels.

Gamut, s. mischievous sport; from game. In De-

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7847) (tudalen 045)

|

used in Herefordshire. 45

vonshire, gammet means fun, merriment: Palmer in v. Gapesing, " To go a

gapesing," is to go sight-seeing. ct We had a famous gapesing."

Probably from to gape, in the sense of to open; viz., to open the eyes. See

Bosworth in Geapan. Compare to trapes ("to go trapesing about"),

from trape. Gaun, s. a measure or tub (z. e. a gallon). In Cheshire,

according to Wilbraham, a gaun is a gallon, Gears and Gearing, s.

horse-harness. In Gloucestershire, only used for filler's or viller's gears;

the harness of the shaft horse of a cart or wagon. Compare Forby in v. To

Geld, v. " to geld anty tumps,'' is to cut off the tops of ant-hills,

and to throw the inside over the land. Giglet, s. a giddy girl. In

Devonshire, according to Palmer, a gigglet is a laughing romp, a tom-boy; for

which reason wakes and fairs are sometimes called gigglet fairs. In

Somersetshire, according to Jennings, gigleting means wanton, trifling, and

is applied to the female sex. Grose states that giglet is a north country

word for a laughing girl. In Norfolk, according to Forby, a gig means a

trifling, silly, flighty fellow. From the A.S. goegl, or gagol, wanton:

Bosworth in v.

|

|

|

|

|

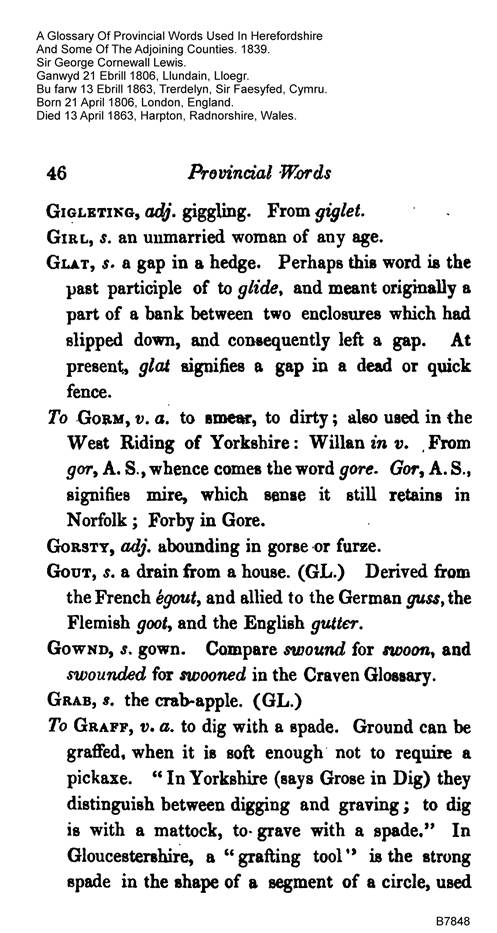

(delwedd B7848) (tudalen 046)

|

46 Provincial Words

Gigleting, adj. giggling. From giglet.

Girl, s. an unmarried woman of any age.

Glat, s. a gap in a hedge. Perhaps this word is the past participle of to

glide, and meant originally a part of a bank between two enclosures which had

slipped down, and consequently left a gap. At present, glat signifies a gap

in a dead or quick fence.

To Gorm, v.a. to smear, to dirty; also used in the West Riding of Yorkshire:

Willan in v. From gor, A.S., whence comes the word gore. Gor, A.S., signifies

mire, which sense it still retains in Norfolk; Forby in Gore.

Gorsty, adj. abounding in gorse or furze.

Gout, s. a drain from a house. (GL.) Derived from the French égout, and

allied to the German guss, the Flemish goot, and the English gutter.

Gownd, s, gown. Compare swound for swoon, and swounded for swooned in the

Craven Glossary.

Grab, s. the crab-apple. (GL.)

To Graff, v.a. to dig with a spade. Ground can be graffed, when it is soft

enough not to require a pickaxe. “In

Yorkshire (says Grose in Dig) they distinguish between digging and graving;

to dig is with a mattock, to grave with a spade." In Gloucestershire, a

"grafting tool 15 is the strong spade in the shape of a segment of a

circle, used

|

|

|

|

|

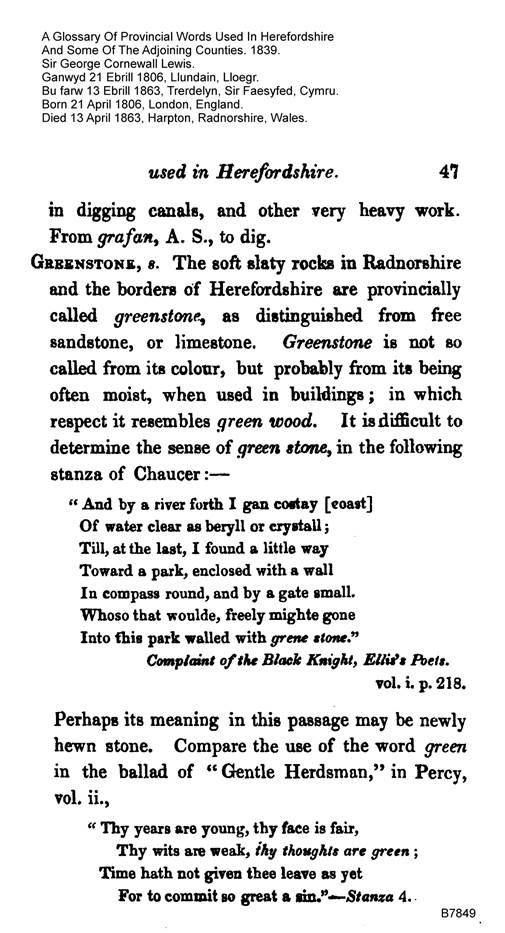

(delwedd B7849) (tudalen 047)

|

used in Herefordshire. 47

in digging canals, and other very heavy work. From grafan, A.S., to dig. Greenstone,

s. The soft slaty rocks in Radnorshire and the borders of Herefordshire are

provincially called greenstone, as distinguished from free sandstone, or

limestone. Greenstone is not so called from its colour, but probably from its

being often moist, when used in buildings; in which respect it resembles

green wood. It is difficult to determine the sense of green stone, in the

following stanza of Chaucer: —

" And by a river forth I gan cost ay [coast] Of water clear as beryll or

crystall; Till, at the last, I found a little way Toward a park, enclosed

with a wall In compass round, and by a gate small. Whoso that woulde, freely

mighte gone Into this park walled with grene sto?ie."

Complaint of the Black Knight, Ellis's Poets.

vol. i. p. 218.

Perhaps its meaning in this passage may be newly hewn stone. Compare the use

of the word green in the ballad of “Gentle Herdsman," in Percy, vol.

ii.,

" Thy years are young, thy face is fair,

Thy wits are weak, thy thoughts are green: Time hath not given thee leave as

yet

For to commit so great a sin." — Stanza 4.

|

|

|

|

|

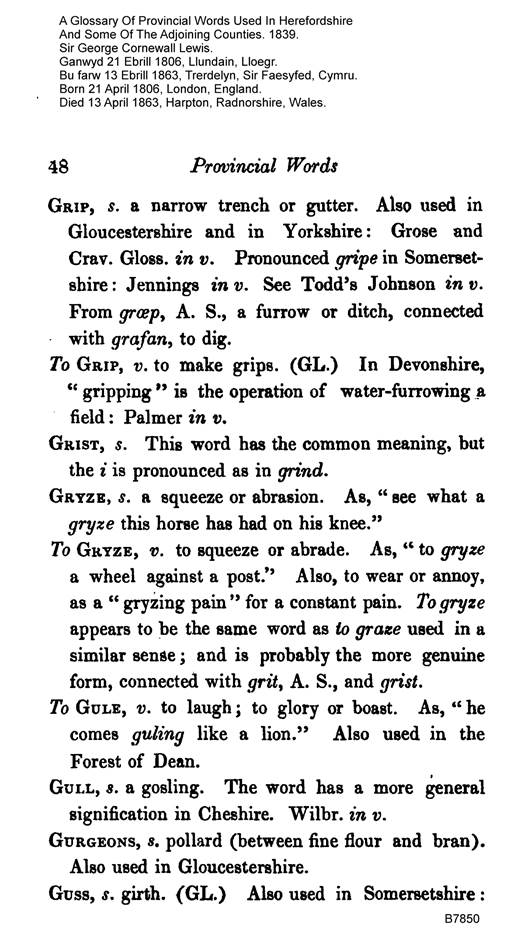

(delwedd B7850) (tudalen 048)

|

48 Provincial Words

Grip, s. a narrow trench or gutter. Also used in Gloucestershire and in

Yorkshire: Grose and Crav. Gloss, in v. Pronounced gripe in Somersetshire:

Jennings in v. See Todd's Johnson in v. From groep, A.S., a furrow or ditch,

connected with grafan, to dig.

To Grip, v. to make grips. (GL.) In Devonshire, “S r ipP m § " i s tne

operation of water-furrowing a field: Palmer in v.

Grist, s. This word has the common meaning, but the i is pronounced as in

grind.

Gryze, s. a squeeze or abrasion. As, “see what a gryze this horse has had on

his knee."

To Gryze, v. to squeeze or abrade. As, “to gryze a wheel against a

post." Also, to wear or annoy, as a “gryzing pain" for a constant

pain. To gryze appears to be the same word as to graze used in a similar

sense; and is probably the more genuine form, connected with grit, A.S., and

grist.

To Gule, v. to laugh; to glory or boast. As, <c he comes guling like a

lion." Also used in the Forest of Dean.

Gull, s. a gosling. The word has a more general signification in Cheshire.

Wilbr. in v.

Gurgeons, s. pollard (between fine flour and bran). Also used in

Gloucestershire.

Guss, s. girth. (GL.) Also used in Somersetshire:

|

|

|

|

|

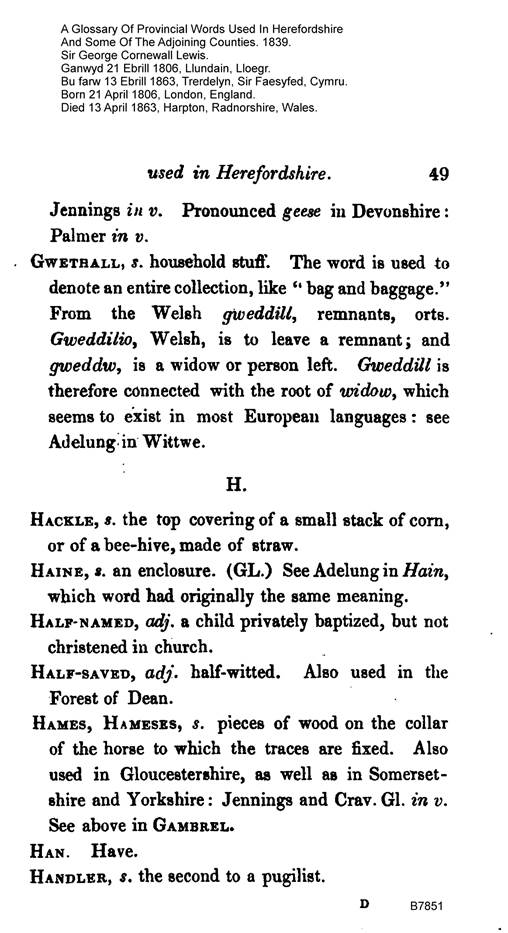

(delwedd B7851) (tudalen 049)

|

used in Herefordshire. 49

Jennings in v. Pronounced geese in Devonshire: Palmer in v. Gwethall, s.

household stuff. The word is used to denote an entire collection, like “bag

and baggage." From the Welsh gweddill, remnants, orts. Gweddilio, Welsh,

is to leave a remnant; and gweddw, is a widow or person left. Gweddill is therefore

connected with the root of widow, which seems to exist in most European

languages: see Adelung in Wittwe.

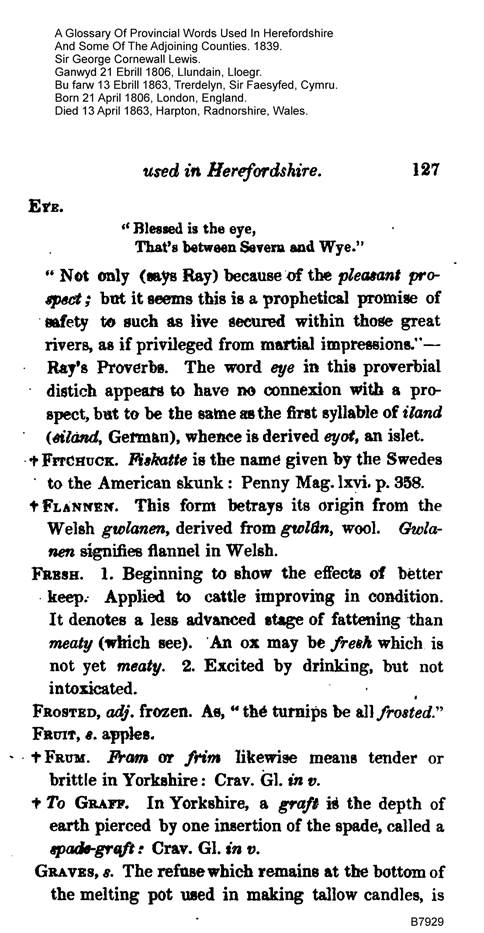

H.

Hackle, s. the top covering of a small stack of corn, or of a bee-hive, made

of straw.

Haine, s. an enclosure. (GL.) See Adelung in Hain, which word had originally

the same meaning.

Half- named, adj. a child privately baptized, but not christened in church.

Half-saved, adj. half-witted. Also used in the Forest of Dean.

Hames, H ameses, s. pieces of wood on the collar of the horse to which the

traces are fixed. Also used in Gloucestershire, as well as in Somersetshire

and Yorkshire: Jennings and Crav. Gl. in v. See above in Gambrel.

Han. Have.

Handler, s. the second to a pugilist.

d

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7852) (tudalen 050)

|

50 Provincial Words

Handy, adv. nearly; as, “handy a mile." (GL.)

Hatch, s. a half-door. Not peculiar.

To Haul, v.a. to carry in a wagon or cart, or simply to draw. Compare the

German holen. To hale is used in the authorized version of Luke xii. 58, “Lest

he hale thee to the judge:" ji^ttote Karaavpn at 7rpog top Kpirrjv.

Haulm, or H&lm, s. used of potatoes, vetches, peas, and beans. That part

of the plant which is above ground. In Suffolk, this word signifies wheat stubble:

Moor in Hahm. According to Grose it is a south country word, In

Gloucestershire, when the ears of wheat are cut off, and the best of the

straw is picked out unbroken, and bound up for the best thatching, it is

called halm.

Hauve, s. the handle of an axe; i. e. the helve. “Helve" is still used

in this sense in Derbyshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk: Grose, Forby, and Moor, in

v. It occurs in Deuter. xix. 5, and see Johnson, in v.

Hay-Making, Gloucestershire. When first cut, it is in swath; it is next

tedded or shaken about; it is then hatched in or raked into small rows to be

put into foot-cocks, the smallest of all cocks. The next day, perhaps, it is

again shaken about and double hatched, or raked by two persons into larger

rows, and put into larger cocks; it is then spread again

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7853) (tudalen 051)

|

used in Herefordshire. 51

and wallied in, or put into still larger rows, called wind-rows, in order to

be put into hay-cocks. These are carried together on poles, called spicks, and

put into wind-cocks.

Head. See to Turn the head.

Heartful, adj. in good spirits.

Heart-whole, or Heart-well, adj. sound as to the vital powers, as well as to

the appetite.

Heavle, *. a dung-heavle is a dung-fork. From to heave “Yeevil" is e<

a dungfork" in the Exmoor dialect (Grose).

Heft, s. weight; also used in Somersetshire: Jennings in v. Formed from

heave, like weft from weave.

Heft, the preterit of “heave." “He heft it," he lifted it.

Herence, Therence, hence, thence (Forest of Dean). Herence is also used in

Somersetshire: Jennings in v.

Hern, pron. hers.

To Hespall, v.a. to harass. This verb appears to be derived from spillan or

gespillan, A.S.

Hickol, or Yackle, s. a woodpecker. Pronounced heccle in Gloucestershire.

Hidlock, s. a state of concealment; as, “he was in hidlock." Also used

in Gloucestershire. Hidlock appears to be formed from hide by a mistaken

d2

|

|

|

|

|

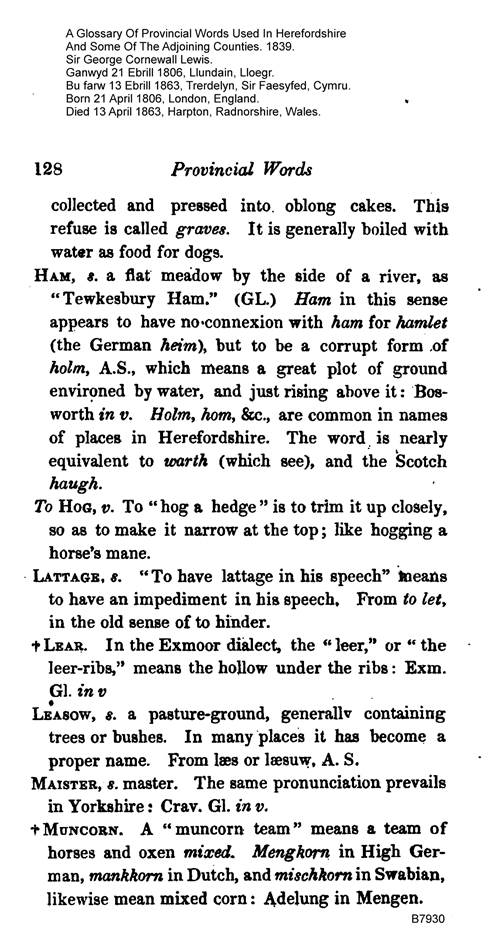

(delwedd B7854) (tudalen 052)

|

52 Provincial Words

analogy to wedlock. The latter word is compounded of median, and lac, a gift;

and therefore the last syllable is not a suffix.

To Hile, v.a. to strike with the horns, as cattle or deer. E.g. ll You had

best take Fillpail out of the leasows; she do hile them young haifers

unmerciful."

Hilt, s. a young sow kept for breeding, which has not had any young. (GL.)

Hindersome, adj. retarding, hindering; as, “the weather is hindersome."

Also used in the Forest of Dean.

Hinge, s. the pluck. (GL.) Pronounced hange in Devonshire: Palmer in v.

Hisn, pron. his, as “It's one of his'n"

Hit, s. a plentiful crop; as, “a hit of apples." The metaphor is

borrowed from striking a mark.

To Hocks, v.a. to cut in an unworkmanlike manner. Used principally in

reference to cutting underwood; the stubs are hocksed, i. e. split and cut

unevenly and irregularly by a person not used to cutting them. From to hack.

Holt, s. hold, dependence on a person or thing; also a place of safety. “To

have holt:" to take hold. When two men are grappling with one another,

they are said to be in holt. Likewise used in Gloucestershire,

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7855) (tudalen 053)

|

used in Herefordshire. 53

Holtless, or Holdless, adj. careless, heedless.

Homber, s. a hammer. See Chimbley.

Hongered, adj. hungry. (GL.)

Hoolet, s. an owl. In Yorkshire the owl is called "hullet:" Craven

Glossary, and Hunter's Hallamshire Glossary, in v. See Grose in Howlet. The

word is old: Nares in Howlet.

Hoop, s. a bullfinch. (GL.)

To Hootch, v. n. to crouch.

Hop-abouts, s. apple dumplings. (GL.)

To Hope, v. to help, i. e. to holp. (GL.)

To Hopple, v.a. to hopple an animal, is to confine its legs, so as to prevent

it from wandering. Also used in Yorkshire and Norfolk: Crav. Gloss. and Forby

in v.

Housen, pi. of house. (GL.)

Howgy, adj. huge, large. An old word: see Nares in Hugy. It occurs in the

ballad of Sir Cauline, Part II. st. 18.

« A hugy giant stiff and stark, All foul of limb and lere."

Also used in the Forest of Dean.

Huck, s. a hook.

Hull, s. the husk of a nut or of grain. This word is also used in Yorkshire and

in Suffolk: Craven Glossary and Moor in v. and in Gloucestershire.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7856) (tudalen 054)

|

54 Provincial Words

Hunch,,?, alump; as, “a hunch of bread or cheese. "

Hurry, s. “We shanna finish it this hurry," i. e. this time, this bout.

Hurtle, s. a spot. It is to be observed that heurte or hurt means a round

blue spot in heraldry. li The field or; three heurtes in bende. These appear

light blewe, and come by some violent stroke: on men they are called hurtes;

but on women they are commonly called tunge moles.' ' Gerard Leigh, Accidens

of Armory, fol. 150. “Heurtes, sorte de torteaux en termes d'armoirie." Borel

Diet, du vieux francais, at the end of Menage. Perhaps hurtleberry, the

bilberry, is connected with this word.

Hummock, s. a mound of earth. From the same root as hum-p.

Hutch, s. a coop; as a rabbit-hutch. In Suffolk, a hutch means a chest: Moor

in v. Huche, in old French, signified a chest or closet; and also a veil for

the head: Roquefort in v. In the will of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford,

who died in 1361, it means a pall over a coffin: Royal Wills (1780), p. 45.

I.

To be III in Oneself is a very common expression for derangement of stomach

or bowels, or slight

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7857) (tudalen 055)

|

used in Herefordshire. 55

fever. If a woman is asked how her husband's arm is, she may reply, “O his

arm be better, but he's ill in hisself, and canna eat his victuals." The

expression is used when a person is affected by an internal disease, of which

the speaker does not know the name.

Ill-relished, adj. disagreeable, as, “an ill-relished person."

Imp, s. a bud, or a young shoot of a coppice which has been felled.

To Imp, v.a. to bud. See Nares in v. Comp. Adelung in Impfen. Imp is likewise

a shoot in Welsh.

Innocent, s. a half-witted person.

To Insense, v.a. to explain to, to make to understand. This word is known in

other parts of England: Grose in v. According to Ray, it is used about Sheffield

in Yorkshire. See also Hunter in v., and Preface, p. xxv. and see Crav. Gl.

in v. It is also used in Gloucestershire. To “make a person sensible^of

anything," is used in a similar manner.

Into, prep, within, short of. “It is not far into a mile."

Inwards, s. the entrails of an animal. (GL.) Also used in Norfolk: Forby in

v. From the A.S. inneivarde, Bosworth in v. It occurs in Shakspeare.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7858) (tudalen 056)

|

56 Provincial Words

J.

Jag, s. a small quantity drawn as a load. The word is similarly used in

Cheshire and in Norfolk: Wilbr. Grose, and Forby, in v. It appears to be derived

from jog; a small load jogged along. In Yorkshire, however, it means a large

cart-load of hay: Crav. Gl. in v.

Jet, s. a descent, a declivity; as, “a bit of a jet to go down." From

the French jef, and therefore analogous to pitch, which see.

Jolly, adj. fat.

K.

To Keech, v. n. to cake, as wax or tallow. Keech and cake appear to be

different forms of the same word.

Keech of Fat, s. the internal fat of an animal, as made up to be sold to a

tallow-chandler. Also used in Gloucestershire. In the first part of Henry IV.,

Prince Henry calls Falstaff “a greasy tallow keech," act ii. sc. 4.,

where the commentators assign to it the meaning first stated. Kichel, in Chaucer,

means a little cake; "a goddes kichel," C. T. 7329, where see

Tyrwhitt's note.

To Keek, v. to be sick, or nearly so. (GL.) Probably connected with the

German keichen, to pant.

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7859) (tudalen 057)

|

used in Herefordshire. 5*7

Kevin, Cavend, or Caving of Beef, s. a part of the round of beef. The same

joint as the lift, which see. From the Welsh cefn, back or ridge.

Kew, s. See Cue.

Kibble, s. a piece of wood 22 inches long, and split to a fit size for

burning. (GL.)

To Kick, v.a. to sting, as a wasp.

Kind, adj. in good health, thriving, prosperous, promising; applied to

animals, vegetables, &c, but not to men. As, “the horse's coat do stare;

he hanna been kind all the sumber. 5 ' “The weather do look very kind"

is also said.

Kindly, adj. prosperous, doing well.

To Knobble, v. to hammer feebly. As, “he canna do much; he do just sit

knobbling over a few stones."

Known, for knew. “I known it very well."

Kyment, adj. stupid.

Kype, s. a coarse wicker basket.

L.

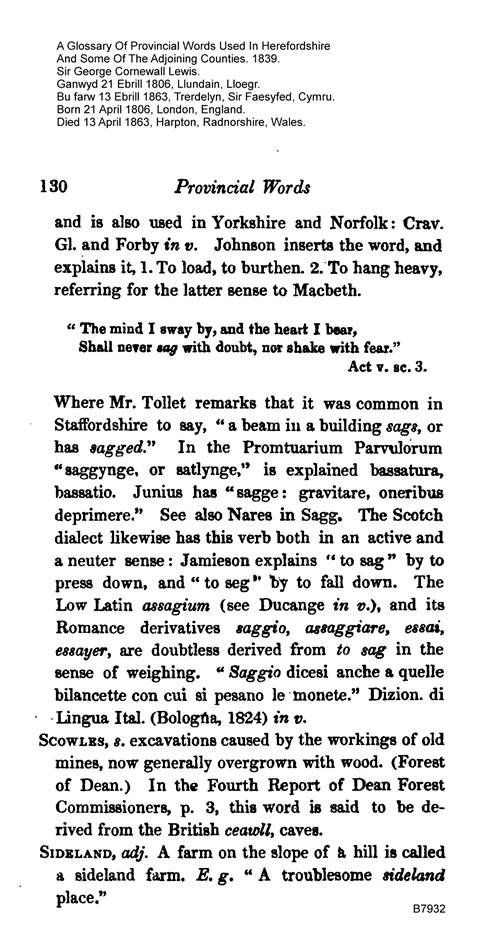

Lagger, s. a broad green lane, little or not at all used as a road. (GL.)

Lammockin, adj. (pronounced lommockin), slouching. Formed from lame: see

Forby in Lammock and Lummox. “Lummakin" is clumsy, heavy, in the Crav.

Gloss.

d3

|

|

|

|

|

(delwedd B7860) (tudalen 058)

|

58 Provincial Words

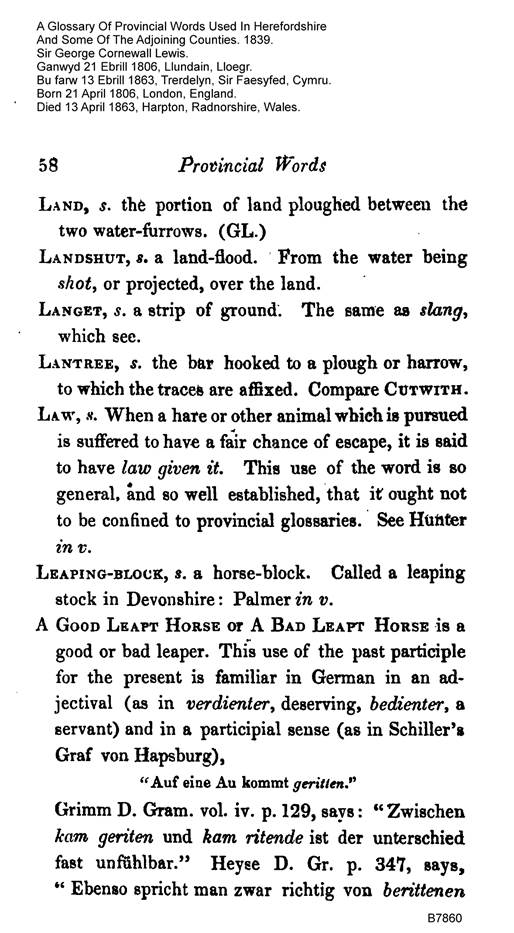

Land, s. the portion of land ploughed between the two water-furrows. (GL.)

Landshut, s. a land-flood. From the water being shot, or projected, over the

land.

Langet, s. a strip of* ground. The same as slang, which see.

Lantree, s. the bar hooked to a plough or harrow, to which the traces are

affixed. Compare Cutwith.

Law t , s. When a hare or other animal which is pursued is suffered to have a

fair chance of escape, it is said to have law given it. This use of the word

is so general, and so well established, that it ought not to be confined to

provincial glossaries. See Hunter in v.

Leaping-block, s. a horse-block. Called a leaping stock in Devonshire: Palmer

in v.

A Good Leapt Horse or A Bad Leapt Horse is a good or bad leaper. This use of

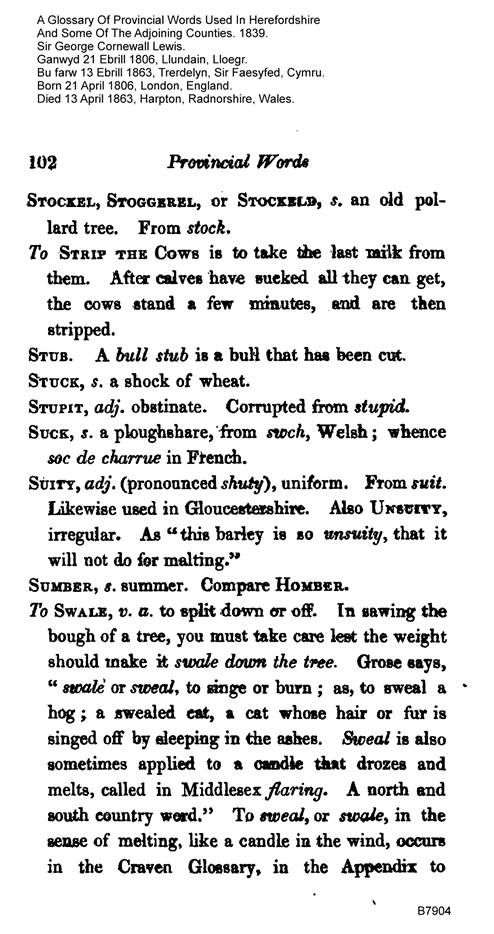

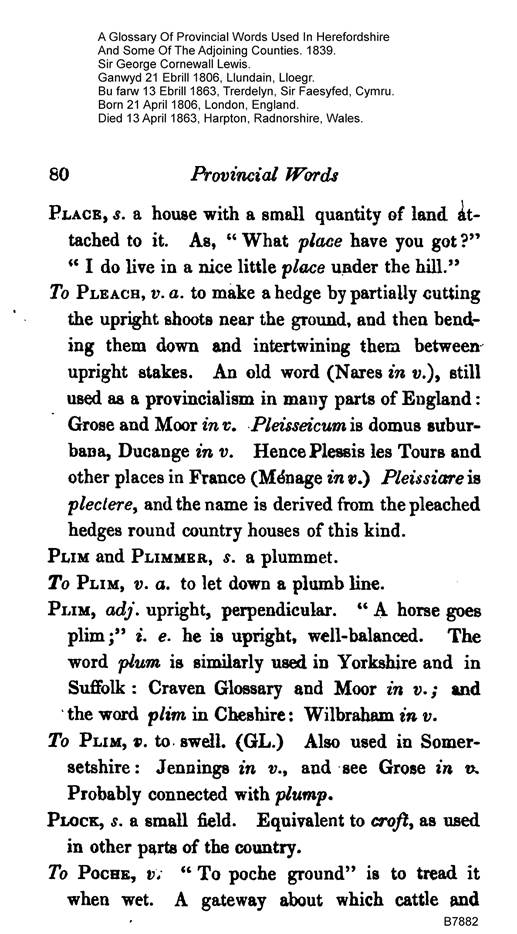

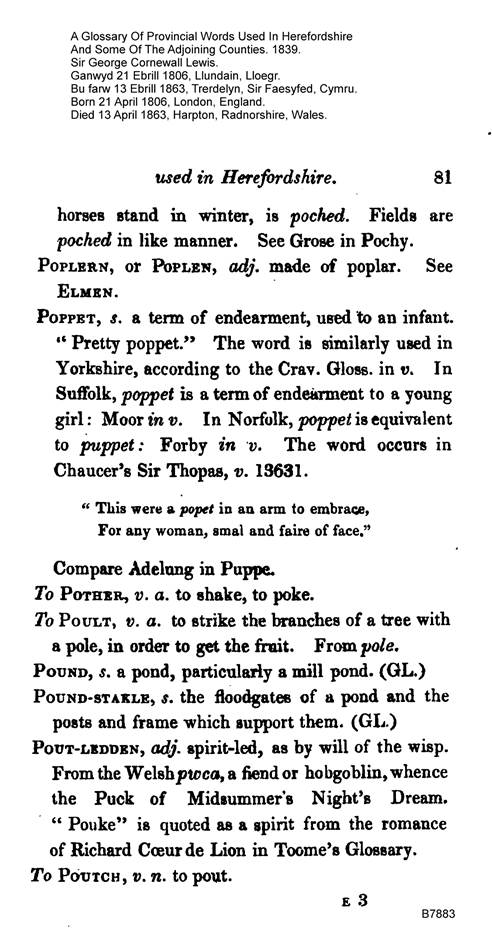

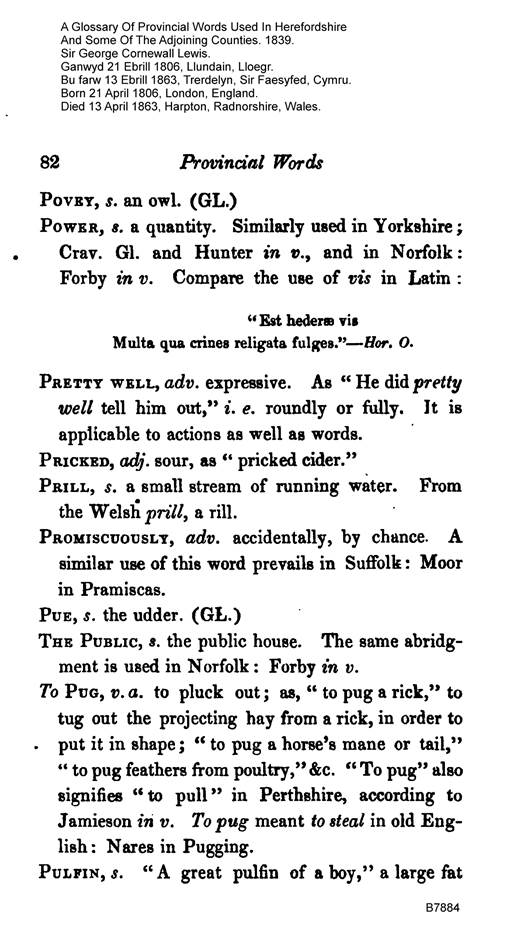

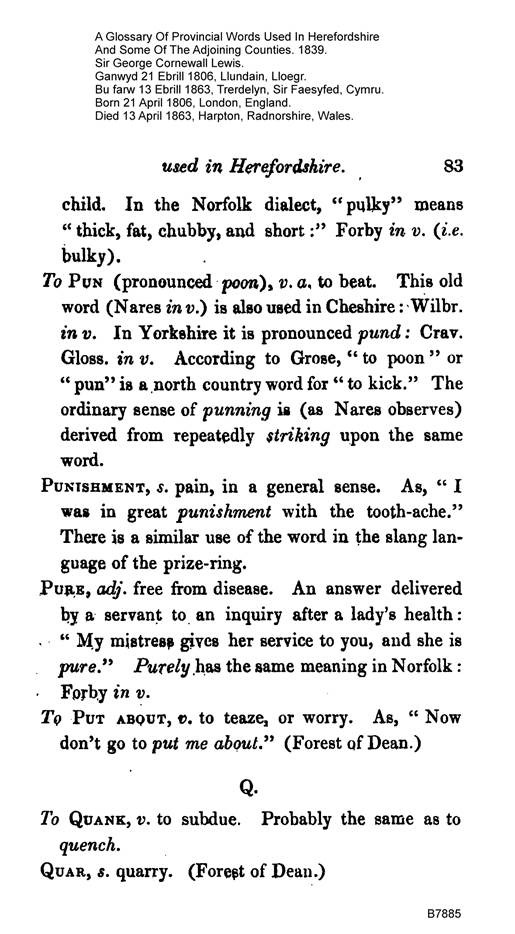

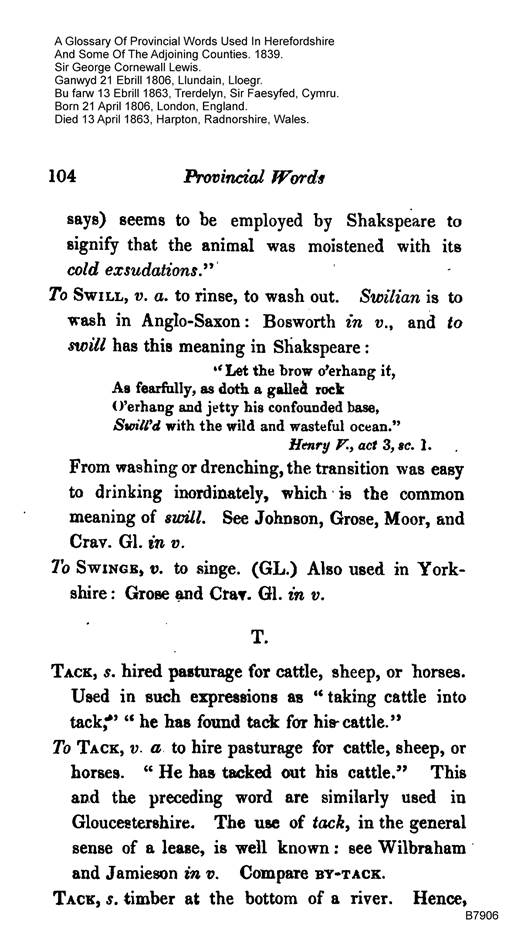

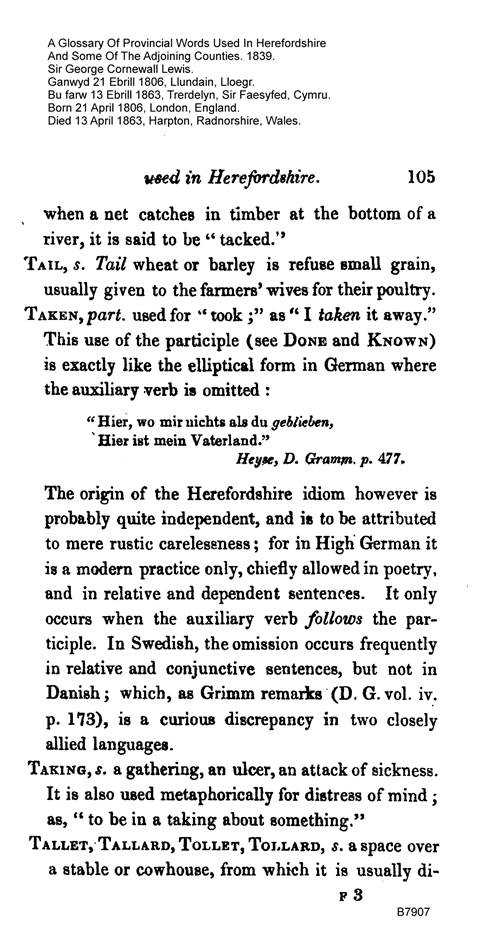

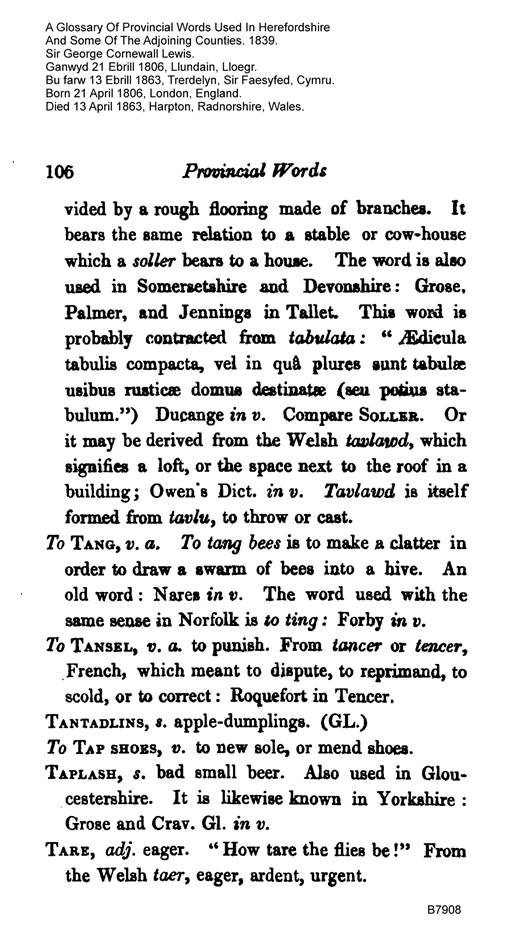

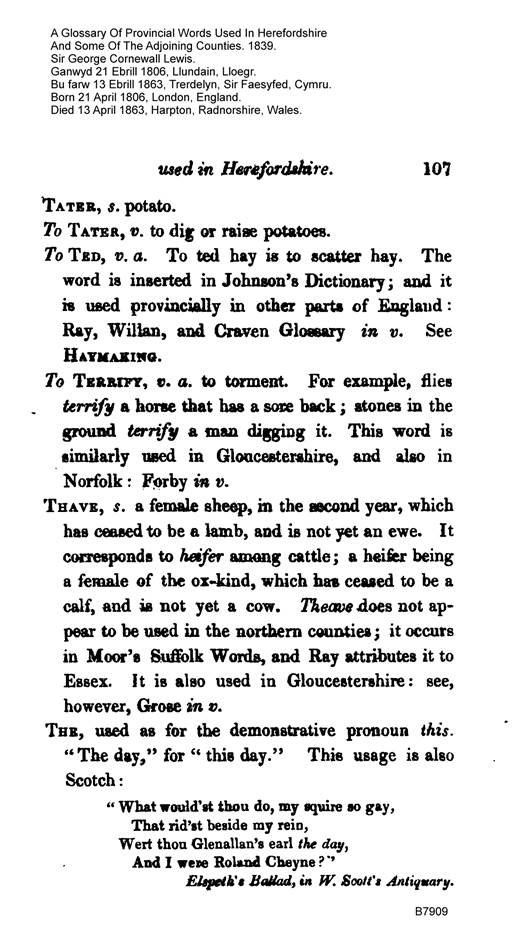

the past participle for the present is familiar in German in an adjectival