.......![]() Gwefan

Cymru-Catalonia

Gwefan

Cymru-Catalonia

|

|

CYNNWYS Y TUDALEN HWN: STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. EVANDER W. EVANS, M.A.ARCHAEOLOGIA CAMBRENSIS. 1873. |

0001 Yr

Hafan kimkat0001

...........0010e Y Barthlen

kimkat0010e

.........................y tudalen hwn / this page

![]() This page in English: (not

available)

This page in English: (not

available)

![]() Aquesta pàgina en català: (no

disponible)

Aquesta pàgina en català: (no

disponible)

Archaeologia Cambrensis - The Journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. VOL. IV. FOURTH SERIES. 1873. xxx130 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. BY EVANDER W. EVANS, M.A., PROFESSOR IN CORNELL UNIVERSITY, ITHACA, NEW YORK. No. II. Since writing my former paper under the above title, I have had opportunity to use Skene's Four Ancient Books of Wales, the latest edition of the oldest extant

MSS. of the old Welsh poets, to wit: the Black Book of Carmarthen (Carm.), referred to the twelfth century;

the Book of Aneurin (B. An.), referred to the thirteenth; the Book of Taliesin (B. Tal.), referred to the begimiing of the fourteenth; and the poetical part of the Red Book of Hergest (Herg.), "compiled at different times in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries." These tests, though disfigured in the edition by numerous errors of typography, in general show less corruption of original forms than the Myvyrian texts, which are, in many cases, printed from later transcripts. The above MSS. contain a few poems belonging to the early middle period (say the twelfth and thirteenth centuries), and a few also which, from internal evidence, may be adjudged to the almost blank eleventh century, the era of transition from old to middle Welsh. But the greater part are undoubtedly of old Welsh origin: indeed, there are strong reasons, in some aspects ably presented by Skene, for believing that some of those associated with the names of Aneurin, Taliesin, and Llywarch Hen, are really based on originals of the sixth and seventh centuries. The translations in Skene, prepared by the Eev. D. Silvan Evans and the Rev. R. Williams, add much that is important to our knowledge xxx140 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. of these venerable remains. Yet they are avowedly tentative and conjectural in many parts: nor, indeed, in the present stage of the study of early Welsh, is it possible that it should be otherwise. It would be unjust to the learned translators to take their rendering of every passage as the expression of their final judgment of its meaning. The elucidation of these ancient and obscure texts (a work which they and others have so ably begun), it will require the best efforts of a whole generation of scholars to complete. In the extracts that follow I preserve the spelling of the editions; but freely deviate from them in punctuation and the use of capital letters, and sometimes also in the separation of words and the division of verse into lines. XI. That species of initial-change which consists in the "provection of the mediae" has been pointed out by Zeuss and others in Armoric and Cornish, but not in Welsh; yet in the oldest Welsh documents we may observe many instances of it. It takes place after strong consonants, notably s and th, ending the preceding words. It is, therefore, due to the assimilating tendency. Thus, in the Black Book of Carmarthen (51): Neus tuc Manauid Eis tull o Trywruid? Did not Manawyd bring Perforated shields from Tribroit? Here tuc is a mutation of duc, brought. Other examples in the Black Book are, ys truc (21) for ys druc, "est malum," and ac nis tirmycco (36) for ac nis diriuycco, "neque eum despiciat." So also in the oldest copy of the Laws: peth peccan (120, bis) for peth beccan, a small matter; guedy es tadkano (148) for guedy es dadkano, after he shall have stated them; kyfreith penfic march (266), the law of borrowing a horse; penfic being a mutation of benfic (beneficium), modern benthyg, a loan; etc. Codex B of Brut Gruffudd ab Arthur has, repeatedly, xxx141 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. pop plwydyn (Myv., ii, 186, 304, 309) for pop blwydyn, every year.

The provection sometimes continues to take place after the infecting consonant has been dropped or depressed: thus, o keill, if he can (Leg. A, 28, 156), where ois for os, and keill for geill; ked kouenho, though he ask (ib., 46), ked being for ket, and kouenho for gouenho. The same fact is seen in Armoric, e.g., ho preur, your brother; ho being for hoc’h, and preur for breur. In later Welsh this mutation disappears, except in a few compounds, e. g., attychwel, return, from at, modern ad, and dychwel.

Among the lately discovered glosses to Martianus Capella, an edition of which has appeared with the learned annotations of Whitley Stokes (1), is orcucetic cors, "ex papyro textili." I think cucetic is, by provection after a strongly uttered r, for guëetic, woven. Compare or Kocled for or Gocled (from the North), in the Venedotian Laws (104).

In Prydain (Britannia) I suspect the provection of the initial was originally owing to the habitual use of the word ynys before it: thus, throughout the Triads, ynys Prydein and ynys Prydain, the Isle of Britain.

XII. Zeuss overlooks the Welsh plural-ending -awr, -iawr, with which we may compare the Armoric -ier.

Plural substantives in -awr are frequent in the old Welsh poets; nor are they very rare in the poets of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. As primitive ā into Welsh au and Armoric e, we may infer - ār the earlier form. This view is corroborated by the rhymes in the Gododin, of which the following stanza contains five of the most common plurals of this form (B. An., 73): Gwyr a aeth Gatracth yg cat yg gawr, Nerth meirch a gwrymseirch ac ysgwydawr; Peleidyr ar gychwyn a llym waewawr A llurugeu claer a chledyuawr. Ragorei, tyllei trwy vydinawr, (1) See, ante, pp. 1-21. xxx142 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. Kwydei bym pymwnt rac y lavnawr — Ruuawn Hir — ef rodei eur e allawr A chet a choelvein kein y gerdawr. Men went to Catraeth arrayed and shouting, A force of horses and brown trappings and shields; Shafts advancing, and keen lances, And shining coats of mail, and swords. He excelled, he penetrated through armies; Five battalions fell before his blades, — Rhuvon the Tall. He was wont to give gold to the altar. And treasure and precious stones to the minstrel. Deprived of initial inflection, the plurals referred to are as follows: ysgwydawr, shields, from ysgwyd, "scutum"; gwaewawr, spears, from gwaew; cledywawr (Armoric

klezeier), swords, from cledyv, modern cleddyf,

Irish claidheamh,; bydinawr, armies, from bydin, modern byddin, old Welsh bodin; llavnawr, blades, from llavn, modern llafn, "lamina." Allawr, rhyming with these plurals, represents an

older altār, Latin "altare." Cerdawr, modern cerddor, is not a plural but a derivative in -ār (Armoric -er, Irish -air, Latin -ārius, Z. 781, 829), signifying a minstrel, from cerd, i. e., cerdd, song; so telynawr, harper, from telyn, harp; drysawr, a doorkeeper, from drws, door; etc. This class of derivatives, which are

numerous, form their plurals in -orion: thus, cerddorion, minstrels. Plurals in -awr are unmistakably indicated by the associated words in such expressions as yt lethrynt lafnawr (B. Tal., 154), blades glanced;

gwaywawr ebrifet (ib., 172), spears without number;

lleithrion eu pluawr

(Gwalchmai, Myv., i, 193), glossy are their plumes. As examples of the plural in -awr in early middle Welsh, I take the following from Cynddelw: llafnawr, blades (Myv., i, 214), bydinawr, armies; aessawr, targets; preidyawr, "praedae" (ib., 243). That plurals of

this form disappeared in later Welsh was owing, doubtless, to a natural tendency to choose forms not admitting of more than one meaning. xxx143 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. The form -iawr occurs a few times, as in the above preidyawr, and in cadyawr, conflicts (B. An., 82).

I had proposed to compare -awr with the Teutonic -er. Professor Hadley, of Yale College, to whose learning and genius I have often been indebted for aid in these studies, suggests that, as the Teutonic -er originally belonged to the stem, and became a distinctive mark of the plural only by being dropped in the singular, so the Welsh -awr probably had a similar history, though, on account of the long quantity of the latter, indicating as it does a primitive -ār, it would be unsafe to assume its identity with the Teutonic -er; that more probably it should be compared with the Latin -āris, or with -ar, gen. -āris, as in "calcar," "laquear," etc. XIII. In the old Welsh poets I find a termination of the second singular, present indicative active, whichdoes not appear to have been noticed in Zeuss or elsewhere. It is usually written -yd, and always rhymes with words which, in middle and modern Welsh, end with the dd sound; hence, in old Welsh, it must have been -id, not -it. Verbs with this ending have been translated variously, but by no author consistently, and scarcely ever correctly. I think the following examples with, after a careful view, be considered decisive as to its true meaning. One of the Urien poems, attributed to Taliesin (B. Tal. 184), begins thus:

Uryen yr echwyd, Haelaf dyn bedyd, Lliaws a rodyd Y dynyon eluyd. Mai y kynnullyd Yt wesceryd. Llawen beird bedyd Tra vo dy uuchyd. Urien of the plain, Most generous of Christians, Much dost thou give To the men of earth. As thou gatherest xxx144 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. Thou dost scatter. Joyful are Christian bards While thy life lasts. The words dy uuchyd, thy life, in the last line, show that the passage is an address, and that the verbs ending in -yd re in the second person. Again, in the Book of Taliesin (1-45): A wdost ti peth wyt Pan vych yn kysewyt?Ae corff ae eneit Ae argel canhwyt? Eilewyd keluyd Pyr nam dywedyd? Restore the rhyme of the second couplet by reading canheit, luminary (modern canaid), then translate:

Knowest thou what thou art When thou art sleeping? A body or a soul Or a hidden light? Skilful minstrel, Why dost thou not tell me? The following is from a religious poem in the Book of Taliesin (180):

Ti a nodyd A ry-geryd O pop karchar. Thou dost help Whom thou lovest Out of every prison. The Red Book of Hergest contains the dialogue entitled Cyvoesi (Ages), between Myrddin and his sister. Gwenddydd says to Myrddin (231): Llallawc, kan am hatebyd, Myrdin uab Moruryn geluyd, Truan a chwedyl a dywedyd. My twin brother, when thou dost answer me. Skilful Myrddin son of Morvyn, Woful is the tale which thou dost tell. Note that truan a chwedyl is archaic for truan o chwedyl. xxx145 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. In a dialogue found in the Black Book of Carmarthen (56), where, it should be observed, the dd sound is represented by t, Ugnach says to Taliesin: Y tebic y gur deduit, Ba hid ei dy a phan doit? Thou that seemest a prudent man, Whither goest thou and whence dost thou come? I submit whether after a comparative study of these passages, which together exhibit nine examples of verbs ending in -yd, it is possible to avoid the conclusion that this termination marks the second person singular, of the present indicative active. It corresponds regularly to the Cornish -yth, -eth, and the Armoric -ez, which belong to the same place. There are many other examples of -yd scattered through the old Welsh poems, and some poems whose old Welsh origin has been questioned; but in place of it we also find -i, as in Irish and in later Welsh. In the unquestioned productions of the twelfth and later centuries, I find no example of -yd. The proverb Gwell nag nac addaw ni wneydd, better a refusal than

a promise which thou dost not perform, I regard as old, though it comes to us in late orthography (Myv., i, 174). We cannot account for -yd by supposing the pronoun ti, thou (Irish tu), to have been suffixed, without

admitting that this is a very old formation, that in fact the t was already depressed to d in old Welsh. This, as before stated, is proved by the words with which the termination rhymes. Thus, in the above extracts it rhymes with deduit, i. e. dedwydd, prudent, a compound which contains the root gwydd, Irish, fiadh, indicating a primitive vid; also with celuid,i. e. celfydd, skilful, old Welsh celmed (Eutych. ); also with eluyd, later elfydd, world, old Welsh elbid (Juv.); also with bedyd, modern bedydd, baptism, old Welsh betid

(Juv.); etc. XIV. The Irish -id of the third singular, present indicative active, is not used in "subjoined" verbs, that is, xxx146 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. in verbs following certain particles, among which are the negatives ni and na, and the verbal ro (Z. 425). This idiom obtains also in Welsh. The termination -it or -id of the same place, as I have elsewhere shown, occurs often in the old Welsh remains; but I have found it only in "absolute" verbs. The fact will be best illustrated by examples where the same verb occurs both as absolute and as subjoined, in the same passage. The following is from Llywarch Hen (Herg. 289): perëid y rydieu, ny phara ae goreu, the trenches remain,

they who made them remain not. Among the ancient proverbs interspersed through the alphabetical collection in the Myvyrian,I find the following: trengid gohid, ni threing molud (iii, 177), riches perish, glory

perishes not; tricid gwr wrth ei barch, ni thrig wrth ei gyvarwys (ib.), a man starves on honour, he does not

starve on bounty; tyvid maban, ni thyv ei gadachan (ib.), the child grows, its clout grows not; chwarëid mab noeth, ni chwery mab newynawg (ib. 152), a naked

youth plays, a hungry youth plays not. So again in the Gosymdaith (Viaticum) of Llevoed Wynebglawr, a versified collection of old Welsh aphorisms (Herg. 307): Ny nawt eing llyfyrder rac lleith; Eughit glew oe gyfarweith. Not usually does cowardice escape destruction; The brave escapes from his conflict. I do not recognize an exception in the nyt echwenit clot kelwyd of the Gosymdaith (Herg. 305). I know of

no verb that will explain echwenit unless it be achwanegu, to increase. The true reading, I think, is nyt echwenic clot kelwyd, falsehood does not advance fame.

The umlauts here postulated are regular. There is a similar example in the Black Book (5), ny dichuenic but pedi, begging does not promote gain. Here we have a

compound dychwanegu. XV. Dr. Davies and other Welsh grammarians very properly give -a as a frequent termination of the third singular, present and future indicative active: compare the Irish -a of the subjoined indicative. Zeuss or his xxx147 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. editor seems to consider this -a, in middle ^Welsh examples, as a part of the stem, as if all the verbs thus ending were derivative verbs in -äu (old Welsh -agu, modern -au, denominative and causative), which preserve the a in conjugation. It is certain that in middle as well as in modern Welsh -a is often used as a termination; and in derivative verbs in -äu it is accordingly often added to the a of the stem, giving -äa, or -aha, or -häa. Thus, in an early-middle translation of Geoffrey's Prophecy of Merlin (Myv., ii, 261-7), arwydocäa, "significat," adurnocäa, "adornabit," atnewydaha, "renovabit,"

grymhäa, "vigebit," etc. In modern Welsh, -äa has

become -â; and in consequence of this synaeresis the accent is thrown on the last syllable. Examples abound also in verbs other than those in -äu: thus (ib.) doluria, "dolebit," from doluriaw; palla, "peribit," irom. pallu; eheta, "convolabit," from ehetec; cerda, " procedet," from cerdet; etc.

The following examples, among others, appear in the oldest copy of the Laws: guada (86), denies, from guadu (ib.); palla (162), fails; gnäa (114), does;

truharhäa (ii, 4), has compassion.

The following are from one of the poems of Cynddelw (Myv., i, 250-1): pwylla, considers; treidia, penetrates; bryssya, hastens; atveilya, decays. The i or y before

-a in the three last examples is foreign to verbs in -äu, that is to say, there are no verbs in -iäu. The infinitives are, pwyllaw, treiddiaw, brysiaw:, and adfeiliaw. In the old Welsh poems, as they come to us, -a as a termination is infrequent but not unknown; thus in Llywarch Hen (Herg. 287, bis), yd äa, goes. We cannot here regard the first a as the verbal particle, for it is not used after the particle yd. XVI. In modern Welsh, the present subjunctive (and optative) terminations are -of, -ot or -ych, -o, -om, -och, -ont. I think it may be shown that the o in these terminations represents an old Welsh oi. In the earliest Welsh MSS., instead of o we often find oe and wy and xxx148 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. sometimes even oy, all of which point to an earlier oi: compare loinou, gl. " frutices," later, llwynau; gloiu, gl. “liquidum," later, gloyw and gloew; etc. The first singular -wyf for -of is not yet obsolete; in middle Welsh it was the usual form. The Venedotian Laws furnish one example of -oef in a talloef (120), "quod reddam." The anomalous -ych of the second singular prevails in middle Welsh; it is found in one old Welsh gloss, anbiic guell, " aue," later, henpych gwell and henffych

gwell, "mayst thou fare better." This is undoubtedly a

pronominal ending equivalent to -yth. The latter occurs nce in the place of -ych in the Book of Taliesin (116): ry-prynhom ni an llocyth tydi vab Meir, may we gain thy protection (lit. that thou protect us) Son of Mary. I find a comparatively recent example in Huw Llwyd of Cynfal (Cymru Fu, 352), who speaks of conscience as one nac a ofnith moi gefnu, whose desertion thou wilt not fear. In the Laws, ych law occurs for yth law, to thy hand (ii, 280, bis). So also in Armoric we find ec’h for the more usual ez, as in ec'h euz, "tibi est." The other second singular form, -of, seems to be modern so far as it appears in books; but it probably came down in some spoken dialect from an old Welsh -oit; in fact the form -wyt also occurs (Z. 512). In the early poets the third singular often has -wy instead of -o, e.g. guledichuy, "dominetur" (Carm., 26), cothvy, i.e. coddwy, "laedat” (ib. 39), digonwy, "faciat"

(B. Tal, 121), carwy, amet (Gwalchmai, Myv., i, 193), rodwy, "det” (ib. 202), syllwy, "videat," catwy, "servet"

(Cynddelw, ib. 217). The Black Book (22) has one example of -oe, in creddoe, "credat." For the first plural -om we find wym in bwym, "simus" (B. Tal. 181). For the second plural -och I have observed no other form. From analogy, however, we may suppose this to represent an old Welsh -oich. In the oldest copy of the Laws the third plural -oent xxx149 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. is quite as common as -ont: thus kafoent, "acquirant" (1O), menoent, “velint" (22), ranoent, “dividant” (34),euoent, “bibant” (106), deuedoent, “dicant” (l52),

kemerhoent, "capiant" (260), etc. Codex E of the Laws has examples of -oynt:

thus deloynt, "veniant,” elhoynt, “eant" (i, 192); llesteyryhoynt, "impediant" (ib. 170); etc. In the Book

of Taliesin -wynt is frequent: thus prynwynt, "assequantur" (109),

ymgetwynt, "caveant" (128), atchwelwynt, " revertantur,"

ceisswynt, “quaerant" (129), etc.

It will hardly be questioned that the old Welsh forms in oi, thus clearly indicated, were primitive optative forms. XVII. I think, however, that the present subjunctive in o had one other source, or rather that there were certain old forms in au (aw), used as future indicative, which by the regular change of au to o early became indistinguishable from the subjunctive forms in o (from oi), and were lost in them.

I begin with the third plural -aunt revealed in the cuinhaunt, "deflebit," (scil. "genus hoc,") of the

Juvencus Glosses (Beitr., iv, 404). I find this termination preserved in a few instances. Thus in the Book of Taliesin (124): Gwaethyl gwyr hyt Gaer Weir gwasgarawt Allmyn; Gwnahawnt goruoled gwedy gwahyn. The wrath of men as far as Caer Weir will scatter the Allmyn; they will make rejoicing after exhaustion. Again (ib. 212-3), pebwyllyawnt ar Tren a Tharanhon, they will encamp on the Tren and the Taranhon; gwerin byt yn wir bydawnt lawen, the populace of the

earth truly will be happy; etc. As -aunt passed into -ont its indicative use did not at once cease; thus we find in the Black Book (27): Gwitil a Brithon a Romani A vvnahont dyhet a divysci. Gwyddyl and Britons and Romans Will create discord and confusion. A third singular -au is also estabHshed by a few examples. Thus in the Book of Taliesin (l50): xxx150 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. Ac Owein Mon Maelgynig denawt A wnaw Peithwyr gorweidawc. And Owain of Mona, of Malgonian custom, Will lay the Picts prostrate. Here gwnaw is for gwnäaw, just as gwnant is for gwnäant.

In a versified collection of proverbs in the Black Book (5) is the following: nid ehalath as traetha ny

chaffaw ae hamhevo, he who does not relate a thing too

amply will not find those that will contradict him. Meilyr ab Gwalchmai, who composed religious poems late in the twelfth and early in the thirteenth century, has the following (Myv., i, 332): Ar Duw adef y nef uy llef llwyprawd Yny edrinaw ury rac y Drindawd Y erchi ym ri rwyf, .... Toward God's abode, toward Heaven my cry will proceed, Until it ascend on high before the Trinity To ask my sovereign King, .... This example, however, and the two next are not decisive as to the mood, the connexions being such as to admit of either the indicative or the subjunctive. In Codex B of Brut GrufFudd ab Arthur (Myv., ii, 305) is the following: a pwy bynac a damweinaw idaw yr ageu honno . . . . , and to whomever that death

shall happen. . . . In a reputed prophecy of Heinin Fardd addressed to Maelgwn Gwynedd (Myv., i, 553), the language of which, however, is middle Welsh, is the following line: mi anfonaf wledd or sygnedd ir neb ai haeddaw, I will

send a feast from the constellations to any one who shall deserve it. As -aw passed into -o its indicative use did not at once cease. Thus in a poem on the Day of Judgment, in the Book of Taliesin (121): Pryt pan dyffo Ef ae gwahano. When he shall come He will separate them. In the predictive poem entitled Daronwy (ib. 148S): xxx151 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. Dydeuho kynrein O amtir Rufein. There will come chieftains From the vicinage of Rome. XVIII. Of the third singular -awt, we have already seen two examples, gwasgarawt and llwyprawd, in the extracts of the last article. Mr. Silvan Evans was the first to point this out as a future-ending (Skene, ii, 424). It is not "-awd, -awdd," however, but -awt, -awd, as we may see wherever it is a rhyming syllable, as in the above llwyprawd. In the old Welsh poetry it occurs often. It also occurs a few times in early-middle productions. Thus in Codex B of Brut Gruffudd ab Arthur the clause "et Gallicanos possidebit saltus," of Geoffrey's original, is rendered a gwladoed Freinc a uedhawt (Myv., ii, 262). The Mabinogi of

Kilhwch and Olwen (Mab., ii, 201, 202) contains three examples: bydhawt, it will be, methawd, it will fail, ymchoelawd, it will turn. Ebel seems to regard the

two last as used optatively (Z. 1097). Lady Charlotte Guest, adopting the sense naturally suggested by the context, translates them as future indicative. I think this termination is not distinctively future, however, but another case of what in Welsh is a general fact, the use of the present to supply the place of a future. If so, we have in -aut, and probably also in -aunt, a remnant of the ā-conjugation. This view is favoured by the crihot, " vibrat", of the Luxemburg Glosses, which have o for au in final syllables. It is favoured also by a few examples in poetry, where the present tense woidd naturally be understood, as in the following proverb of the Gosymdaith (Herg., 307): gwisgawt coet kein gowyll, the wood wears a fair hood.

XIX. The common middle Welsh conjugation of the perfect active indicative is -eis, -eist, -awd(d), -asom, -asawch, -asant. The third singular, however, had besides -awd(d), the endings -u'ys, -as, -es, and -is. To these I must add -essit, -yssit, -sit, of which there are evident examples in the early poetry, though they have xxx152 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. generally been confounded by translators with the similar terminations of the pluperfect passive impersonal. The Gododin (B. An., 71), in recounting the deeds of one of its heroes, says: seinyessyt e gledyf ym penn mameu, his sword resounded in the head of mothers

(that is, he killed the sons). The following is from a religious poem in the Book of Taliesin (181):

Prif teyrnas a duc Ionas o perued kyt; Kiwdawt Ninieuen bu gwr llawen pregethyssit. The Chief of Sovereignty brought Jonah from the belly of the whale; To the city of Nineveh it was a joyful man that preached. Kiwdawt is Latin "civitāt-"; kyt is Latin "cetus."

The translators in Skene recognise the perfect active in the above examples. Why not also in the following? Kewssit da nyr gaho drwc (B. Tal., 148), he has found

good who does not find evil. This aphorism, in a later form, appears in the Myvyrian collection (iii, 150): cavas dda ni chavas ddrwg, he has found good who has

not found evil. The next is from Cynddelwv (Myv. i, 224): Llary Einnyawn lluchdawn llochessid Veirtyon — vab kynon clod venwyd. Gentle Einnyawn, lavish of gifts, protected The bards — the son of Cynon, the glory of wit. The next is from Meilyr ab Gwalchmai (Myv., i, 324): Delyessid Yeuan yeuangc deduyt Diheu uab Duu nef yn dufyr echuyt. John the young, the wise, held The true Son of God in the water of the plain. From the same (ib.): prynessid mab Duu mad gerennhyt, the Son of God purchased a blessed friendship. In Brut Gruffudd ab Arthur (Myv., ii, 249) there is an example of -assit: ar gwenwyn hwnnw trwy lawer o amser ac llygrassyd, and that poison [the Pelagian

heresy] for a long time corrupted them. Geoffrey's original here has the pluperfect: "cujus venenum ipsos multis diebus afiecerat." But the translation in the xxx153 STUDIES IN CYMRIC PHILOLOGY. Brut is free. The rest of the above examples, either on the face of them, or in view of the connexions in which they occur, are decisive, and indicate the perfect. May we not compare here the -sit of Latin perfects in si? XX. The Welsh perfect passive forms in -at and -et are doubtless perfect participles which passed into finite verbs by the habitual omission of the auxiliary, — the place of the participle being in the meantime supplied by the verbal adjective in -etic, with which Ebel compares Latin " dediticius," “facticius," "suppositicius," etc. These changes must have taken place at a very early period; yet I find a few middle-Welsh examples where the participle, in composition with the auxiliary oedd, was, retains its proper meaning. I am not aware

that they have been pointed out. The following are from Brut Gruffudd ab Arthur: keyssyaw y wlat ry-vanagadoed udunt (Myv., ii, 103), to seek the country which had been mentioned to them; pym meyb hagen a anadoed ydaw (ib., 160), there had been born to him, however, five sons; a megys y dyscadoed ydaw, brywaw y pryvet a oruc (ib., 170),

and as it had been taught him, he bruised the insects; megys yd archadoed (ib., 286), as it had been commanded.

The following is a stanza of uncertain authorship, printed among the early-middle poems in the Myvyrian (i, 254): Eurwas kyn lleas, yn llyssoet enwawc Mygedawc magadoet O bob da dofnytadoet; O bob defnyt deifnyawc oet. The illustrious youth, before he perished, had been bred in famous and grand courts. Of every good was he composed; in every matter be was skilled. The verbs here to be noticed are, managad-oedd, ganad-oedd, dyscad-oedd, archad-oedd, magad-oedd, dafnyddad-oedd. They are not imperfects, as the similar

combinations in Armoric are, e. g., oa caret, was loved; but pluperfects, like the Latin "amatus erat." ________________________________

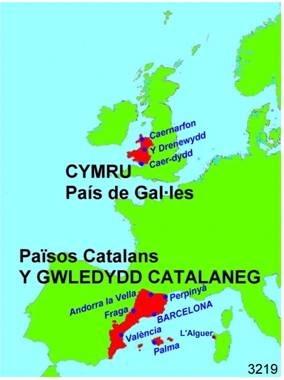

(llun 3219)

http://www.kimkat.org/amryw/1_cymraeg/cymraeg_ieitheg-1873_archaeologia-cambrensis_2918k.htm

Cysylltwch â

ni trwy’r llyfr ymwelwyr: kimkat0860k

Ble'r wyf i? Yr ych chi'n ymwéld ag un o

dudalennau'r Gwefan "CYMRU-CATALONIA" (Cymráeg)

On sóc? Esteu visitant una pàgina de la Web "CYMRU-CATALONIA" (= Gal·les-Catalunya) (català)

Where am I? You are visiting a page from the

"CYMRU-CATALONIA" (=

Wales-Catalonia) Website (English)

Weø(r) àm ai? Yùu àa(r) víziting ø peij fròm dhø "CYMRU-CATALONIA" (= Weilz-Katølóuniø) Wébsait

(Íngglish)

Adolygiad diweddaraf: 2012-11-08,

2008-09-27, 2006-10-31

Diwedd y dudalen